Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-10-17

Date: 28-1-2022

Date: 2023-11-07

|

The presentation of situations as possible or necessary, point (2.) above, is achieved in English by modal verbs. The essential distinction in this area is between epistemic and deontic modality.

‘Epistemic’ derives from the Greek episteme (knowledge), and epistemic modality relates to the way (the mode) in which speakers know a situation; do they know that it exists, do they consider it as merely possible or do they treat it as necessarily existing (although they have not seen it themselves) on the basis of evidence?

‘Deontic’ derives from the Greek verb deo (tie). Deontic modality relates to whether speakers present a situation as possible because permission has been given, or as necessary because circumstances require it, for example because someone with authority has issued a command or because the situation is such that other actions are ruled out.

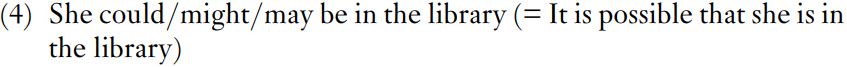

Epistemic possibility is expressed by could, may or might, as in (4).

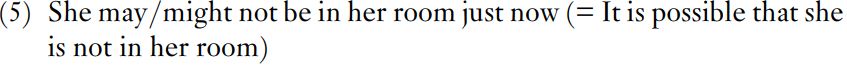

May is neutral but might and could express more remote possibility. Note that can is not excluded in principle from expressing epistemic possibility but occurs very rarely with this interpretation. In addition to asserting that propositions are epistemically possible, speakers assert that they are epistemically not possible, as in (5).

May is neutral but might and could express more remote possibility. Note that can is not excluded in principle from expressing epistemic possibility but occurs very rarely with this interpretation. In addition to asserting that propositions are epistemically possible, speakers assert that they are epistemically not possible, as in (5).

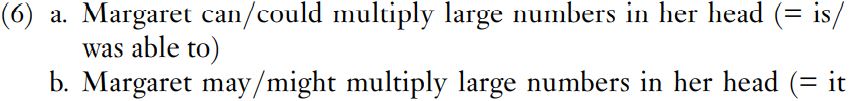

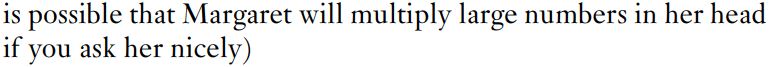

Can/could and may/might derive historically from different verbs and diverge in meaning to the extent that can and could can be used to refer to physical or mental ability, whereas may and might cannot. Example (6a) is quite different in meaning from (6b).

Can/could and may/might derive historically from different verbs and diverge in meaning to the extent that can and could can be used to refer to physical or mental ability, whereas may and might cannot. Example (6a) is quite different in meaning from (6b).

When negated, can and could behave very differently from may and might. Example (7) expresses a stronger commitment to the impossibility of a situation. The gloss is ‘it is not possible that such and such’, as opposed to ‘it is possible that not such and such’ for (5).

Speakers may also present situations as epistemically necessary, that is, they can convey the message ‘I conclude from the evidence that this event happened/is going to happen’. Must is typically used, as in (8).

Speakers may also present situations as epistemically necessary, that is, they can convey the message ‘I conclude from the evidence that this event happened/is going to happen’. Must is typically used, as in (8).

Speakers also use have to and have got to, which express necessity but are not modal verbs because they do not have the typical syntax of modal verbs: That’s got to be the worst joke I’ve ever heard.

Many examples of epistemic necessity can be glossed by means of I conclude that, as in (9), which could be uttered as the speaker looks at piles of empty beer cans.

Speakers can also conclude that something is necessarily not the case. They can’t be going to tell us used to be the standard British English construction, but They mustn’t be going to tell us is the regular construction for speakers of Scottish English and speakers of American English and is moving into standard English English.

Speakers can also conclude that something is necessarily not the case. They can’t be going to tell us used to be the standard British English construction, but They mustn’t be going to tell us is the regular construction for speakers of Scottish English and speakers of American English and is moving into standard English English.

Deontic possibility has to do with giving or withholding permission. Grammar books used to assert that may is used in this sense, but the bulk of speakers both in the UK and in North America use can. Permission can be given to do something or not to do something; the latter is typically expressed by verbs other than may. Having permission not to do something is equivalent to not being obliged to do something, and the typical expressions are, for example, You don’t have to come to work tomorrow and You don’t need to come to work tomorrow. In contrast, not having permission to do something is expressed by may not [the standard story] or can’t/cannot: You may not/can’t/cannot hand in your dissertation late.

Deontic necessity is expressed by must, have to and have got to. The typical account in grammars of English is that must expresses an obligation placed on individuals by themselves (I must read that new novel because I enjoyed all her other novels) as opposed to an obligation placed on individuals by others or by circumstances (I have to read that novel because there’s an obligatory question on it in the exam, or I have to go to the dentist because the toothache keeps waking me up). This analysis of must and have to does not fit the facts of usage. Speakers recognize have got to as expressing obligations placed on individuals by others or by circumstances. Have to is neutral, and must is peripheral for many speakers (as opposed to writers).

As mentioned in the paragraph following example (8) above, have and have got to are used for the expression of epistemic modality. The original meaning of have and have got to was and is deontic, that is, some action is necessary because circumstances make it so. The use of these verbs in examples such as That has to be the worst joke I’ve ever heard is more recent. Similarly, the use of ought and should has changed. Their original meaning is one of moral obligation, as in He should help his friends, not laugh at them. Another use, possibly derived from the moral-obligation interpretation, is exemplified in The computer desk should hold together now that I’ve put in extra screws. A moral obligation is weaker and more easily avoided than an obligation imposed by circumstances, and this difference between ought and should on the one hand and have and have got to on the other is reflected in the epistemic uses. Speakers who say That book should be in the library draw conclusions from whatever evidence is available to them, such as patterns of book-borrowing or the fact that they returned the book to the library just twenty minutes before. But they draw a much weaker conclusion than speakers who say the book must be in the library. The latter statement indicates that no other conclusion is possible, whereas should leaves room for the conclusion to be wrong.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|