Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Postscript to so-called language relativity

المؤلف:

ERIC H. LENNEBERG

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

553-30

2024-08-25

1214

Postscript to so-called language relativity

The term language relativity is due to B. L. Whorf, although similar notions had been expressed before by many others (Basilius, 1952). In his studies of American Indian languages, Whorf was impressed with the general difficulties encountered in translating American Indian languages into European languages. To him there seemed to be little or no isomorphism between his native English and languages such as Hopi or Nootka. He posed the question, as many had done before him, of whether the divergences encountered reflected a comparable divergence of thought on the part of the speakers. He left the final answer open, subject to further research, but it appears from the tenor of his articles that he believed that this was so, that differences in language are expressions of differences in thought. It has been pointed out since (Black, 1959; Feuer, 1953; but see also Fishman, 1960) that there is actually little a priori basis for such beliefs.

The empirical research (partly stimulated by Whorf’s own imaginative ideas) indicate that the cognitive processes studied so far are largely independent from peculiarities of any natural language and, in fact, that cognition can develop to a certain extent even in the absence of knowledge of any language. The reverse does not hold true; the growth and development of language does appear to require a certain minimum state of maturity and specificity of cognition. Could it be that some languages require ‘less mature cognition’ than others, perhaps because they are still more primitive? In recent years this notion has been thoroughly discredited by virtually all students of language. It is obvious that on the surface every language has its own peculiarities but it is possible, in fact assumed throughout this monograph, that languages are different patterns produced by identical basic principles (much the way sentences are different patterns - in¬ finitely so - produced by identical principles). The crucial question, therefore, is whether we are dealing with a universal and unique process that generates a unique type of pattern. This appears to be entirely possible. In syntax we seem to be dealing always with the same formal type of rule and in the realm of semantics we have proposed that the type of relationship between word and object is quite invariant across all users of words. It is due to this uniformity that any human may learn any natural language within certain age limits.

When language learning is at its biological optimum, namely in childhood, the degree of relatedness between first and second language is quite irrelevant to the ease of learning that second language. Apparently, the differences in surface structure are ignored and the similarity of the generative principles is maximally explored at this age. Until rigorous proof is submitted to the contrary, it is more reasonable to assume that all natural languages are of equal complexity and versatility and the choice of this assumption detracts much from the so-called relativity theory.

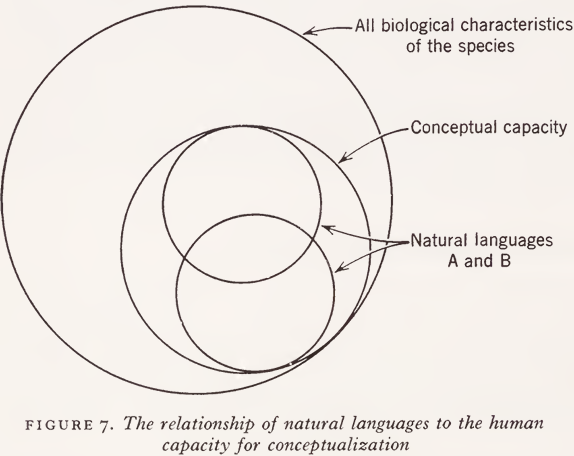

Since the use of words is a creative process, the static reference relationships, such as are apparent through Approach A or as they are recorded in a dictionary, are of no great consequence for the actual use of words. However, the differences between languages that impressed Whorf so much are entirely restricted to these static aspects and have little effect upon the creative process itself. The diagram of Fig. 7 may illustrate the point. Common to all mankind are the general biological characteristics of the species (outer circle) among which is a peculiar mode and capacity for conceptualization or categorization. Languages tag some selective cognitive modes but they differ in the selection. This selectivity does not cripple or bind the speaker because he can make his language, or his vocabulary, or his power of word-creation, or his freedom in idiosyncratic usages of words do any duty that he chooses, and he may do this to a large extent without danger of rendering himself unintelligible because his fellow men have similar capacities and freedoms which also extend to understanding.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)