Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

CONTEXTUAL DETERMINANTS IN COMMON NAMING

المؤلف:

ERIC H. LENNEBERG

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

543-30

2024-08-25

1250

CONTEXTUAL DETERMINANTS IN COMMON NAMING

The insight gained through the application of Approach B still gives an inaccurate picture of how the naming of phenomena proceeds. The structure of the name maps might induce us to believe that the English word red can only be used for a very few colors (the focus of the region ‘ red ’); and that as we move away from the focus the word would always have to be qualified as for instance yellowish-red, dirty red, etc. However, when one refers to the color of hair, or the color of a cow, or the skin color of the American Indian the word red is used without qualifiers. Conversely, the physical color which is named brownish-orange when it appears in the Munsell Book of Colors, and red when it is the color of a cow, may be called ochre when it appears on the walls of a Roman villa.

Quite clearly the choice of a name depends on the context, on the number of distinctions that must be made in a particular situation, and on many other factors that have little to do with the semantic structure of a given language per se; for example, the speaker’s intent, the type of person he is addressing himself to, or the nature of the social occasion may easily affect the choice of a name.

Only proper names are relatively immune from these extra-linguistic determining factors. But although the attachment of the name Albert Einstein to one particular person remains completely constant, it implies that in instances such as these the most characteristic aspect of language is eliminated, namely the creative versatility - the dynamics - and it may well be due to this reduction that proper names are not ‘felt’ to be part of a natural language. Once more we see that there are usually no direct associative bonds between words and physical objects.

It is also possible to study empirically the naming behavior that is specific to a given physical context. This was first done by Lantz and Steffire (1964), who used a procedure which we may call Approach C. In this method subjects are instructed to communicate with each other about specific referents. There are several variants for a laboratory set-up. The easiest is as follows: two subjects are each given an identical collection of loose color chips. The subjects may talk to each other but cannot see each other. Subject A chooses one color at a time and describes it in such a way that subject B can identify the color chip. For instance, subject A picks one color and describes it as ‘the color of burned pea soup’. Subject B inspects his sample and makes a guess which color the other subject might have picked; the experimenter records the identification number of both colors and measures the magnitude of the mistake (if any) in terms of the physical distance between the colors.1 If this procedure is done on a sufficiently large number of subject-pairs one may statistically reduce individual competence factors and come up with a measure, called communication accuracy, that indicates how well each of the colors in the particular context presented may be identified in the course of naming behavior.

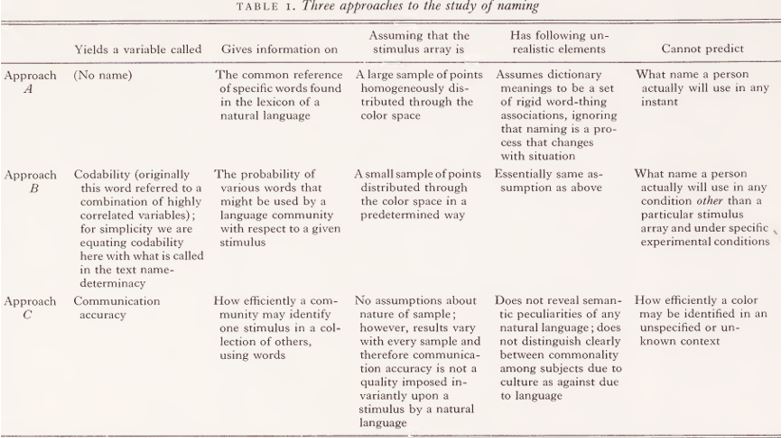

Note that Approach C, leading to the estimation of communication accuracy, no longer indicates exclusively the nature of the relationship between particular words and objects and is thus somewhat marginal to the problem of reference. For instance, a given color chip, say a gray with a blue-green tinge, may obtain a very low communication accuracy score if it is presented together with fifty other grays, greens, blues, and intermediate shades, but a very high score if it is presented with fifty shades all of them in the lavender, pink, red, orange, and yellow range. Although this approach emphasizes the creative element of namipg, it probably does not distinguish between the peculiar semantic properties of one natural language over another. The difference between the three approaches is summarized in Table 1.

1 This is possible if we choose a linear stimulus array with perceptually equidistant stimuli as, for instance, described by Lenneberg, 1957.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)