Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Are there specifically linguistic universals?

المؤلف:

DAVID McNEILL

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

530-29

2024-08-24

1200

Are there specifically linguistic universals? 1

This paper presents the argument that it is quite impossible to say, at the moment, if the structure of thought influences the structure of language. One might reasonably ask why such an argument needs to be presented. For obviously thought affects speech, at least under favorable conditions, and the structure of English (for instance) obviously is not the same as the structure of thought. There would thus seem to be no room for argument. That thought influences language is either obviously right or it is obviously wrong.

There is, however, a sense in which the influence of thought on the structure of language is not obvious. In fact, in this further sense, the question remains entirely open and no one can yet say what connection, if any, there is between thought and language. But that is the argument of the paper.

To explain the argument it is necessary first to describe how language appears to be acquired. The account will necessarily be brief; a more complete description can be found elsewhere (McNeill, 1970).

The structure of language is largely abstract. Most of what one knows about sentence structure is not indicated in any acoustic signal. It is not indicated even in the arrangement of words as uttered in sentences. Everyone knows, for example, that Mary and see go together differently in Mary is eager to see and Mary is easy to see. The grammatical relation between the two words differs in these sentences but the difference is not present to the senses. It is abstract. Since this is the case, and since in general each of us has access to linguistic information that cannot be displayed, a question arises as to how we when children ever acquired such undisplayable information. Let us call this the problem of abstraction. It is through an attempt to solve the problem of abstraction that the effect of thought on language becomes an important theoretical possibility.

The problem of abstraction is not, of course, unique to language development. It appears also in perceptual development and in the development of manual skill, to mention just two situations. It appears whenever the result of experience differs systematically from experience itself. A grammar is systematically different from the sentences a child experiences. The visual perception of three dimensions and the ability to organize a series of movements into a single act of reaching (Bruner, 1968) are systematically different from the visual and tactual stimulation that support them. The way abstraction is overcome in development, however, may not be the same in these situations. The point of this paper is that such questions cannot be prejudged. What follows, therefore, might be unique in all respects to language; we return to this equivocation at the end, for it has an origin more profound than simple caution in the face of surprising Nature.

A hypothesis about the acquisition of language, focusing directly on the problem of abstraction, holds that the ‘concept of a sentence’ appears at the beginning of language acquisition. It is not something arrived at after a long period of learning. It is, rather, something that organizes and directs even the most primitive child speech. The facts of language acquisition cannot be understood in any other way. The concept of a sentence is a method of organizing linguistic information, including semantic information, into unified structures. Words fall into grammatical categories and the categories are related to one another by specific grammatical functions, such as subject, predicate, object of verb, etc. The concept of a sentence can appear so early, before grammatical learning has taken place, because it reflects specific linguistic predispositions, some of which might be innate.

The successive stages of language acquisition in this view result from a progression of linguistic hypotheses, which children invent, regarding the way the concept of a sentence is expressed in their language. The term ‘hypothesis’ is used here in the sense of a tentative explanation subject to empirical confirmation; it does not necessarily imply that the processes of invention and test take place consciously (but cf. Weir, 1962, for examples of apparently deliberate hypothesis testing).

Children everywhere begin at 12 to 14 months with the same initial hypothesis: the concept of a sentence is conveyed by single words. By 18 or 24 months, typically, this hypothesis is abandoned for another: the concept of a sentence is expressed through combinations of two and three words. This hypothesis is in turn abandoned and new ones are adopted, presumably under the pressure of adult speech, which at the outset consists entirely of negative examples. There is in this way a constant elaboration of the forms through which the more or less fixed concept of a sentence is expressed. The consequence is that the concept of a sentence becomes steadily more abstract. Thus, the concept of a sentence does not have to be displayed in the form of specimens, for children themselves make it abstract. We should note that the process of language acquisition gives to adult grammar a certain necessary arrangement. The part of the underlying structure that defines the concept of a sentence will exist in every language, but it will be related via transformations to surface structures that contain many idiosyncracies. Such is the universal form of grammar, according to the linguistic theory developed by transformational grammarians.

Three examples will be cited in connection with this view of language acquisition. Two come from different places on the developmental line that children follow in expressing the concept of a sentence. The third comes from a developmental line that appears to run in a completely different direction. Let us first consider the holophrastic period of development. Many linguists and psychologists have observed that young children express something like the content of full sentences in single-word utterances. But what has not been realized is that the concept of a sentence undergoes a continuing evolution throughout the holophrastic period. Children do not express ‘something like’ sentences with single words, therefore, they express precisely the relations that define the concept of a sentence, these relations appearing one by one during the second year of life. My examples are drawn from a diary kept by Dr P. Greenfield, who was to my knowledge the first to notice this phenomenon. The initial step seems to be the assertion of properties. At 12 months and 20 days (12; 20) the child said hi when something hot was presented to her, and at 13; 20 she said ha to an empty coffee cup - clearly a statement of a property since the appropriate thermal stimulus was absent. At 14; 28 the child first used words to refer to the location of things as well as to their properties. She pointed to the top of a refrigerator, the accustomed place for finding bananas, and said nana. The utterance was locative, not a label or an assertion of a property, since there were no bananas on the refrigerator at the time. A short while later a number of other grammatical relations appeared in the child’s speech. By 15; 21 she used door as the object of a ‘verb’ (meaning ‘close the door’), eye as the object of a ‘preposition’ (after some water had been squirted in her eye), and baby as the subject of a ‘sentence’ (after the baby had fallen down).

By the time words are actually combined several grammatical relations have become available and have been available for several months. Greenfield’s daughter first combined words at 17 months but at 15 months had expressed such relational concepts as attribution, location, subject, and object. Combining words is a new method for expressing these same relations. Thus the expression of sentences changes while the concept of a sentence itself does not. Far from being the product of grammatical learning, therefore, the concept of a sentence is the original organizing principle for grammatical learning. There is a constant attempt by a child to enlarge the linguistic space through which this concept passes. It is impossible to say on current understanding why children begin to combine words. Doing so reflects a fundamentally different view of the nature of language: whereas previously any word could appear in almost any relation, now many words appear in only one relation.

The result contrasts very sharply with what had existed before. There is a definite restriction on the patterns that appear as word combinations. One child, Adam, whose speech was first studied at 26 months, will serve as a convenient example. A distributional analysis of Adam’s speech resulted in three grammatical classes: modifiers, nouns, and verbs. With three grammatical classes there are (3)2 = 9 possible two-word combinations and (3)3 = 27 possible three-word combinations. Of this set of possibilities only 4 two-word and 8 three-word combinations actually occurred. Every one of the occurring combinations corresponded to one or more of the formal definitions of the basic grammatical relations, as contained in linguistic theory (for further discussion, see McNeill, 1966). There were utterances such as Mommy come and eat dinner but there were none such as come eat dinner. The first corresponds to the subject-predicate relation, the second to the verb-object relation, and the third to no relation - it is the result of conjoining two independent sentences, each of which separately embodies a basic grammatical relation. It is worth pointing out that surface structures like come and eat dinner are abundantly exemplified in the speech of adults, but the abstract relations underlying such surface sentences can be understood only if the transformational operation of conjunction is understood. Adam at 26 months had not discovered this operation.

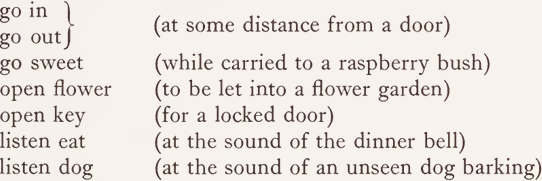

Between Greenfield’s diary and Adam’s speech at 26 months a complete change has taken place in the expression of the concept of a sentence. There is however continuity in the concept expressed. It is fairly clear, moreover, that children possess a specific ability to express the concept of a sentence through combinations of words; it does not result merely from uttering words in combination. Gardner and Gardner (1969) have begun a fascinating attempt to teach a chimpanzee to ‘speak’ English by means of deaf-mute signs. By the use of signs Gardner and Gardner hoped to overcome the entirely peripheral limitations that they supposed had obstructed previous attempts to teach chimpanzees to speak (e.g., Kellogg and Kellogg, 1933), and there can be little doubt that this supposition is correct. Washoe, as the chimpanzee is called, has a well established vocabulary of some 30 words at 25 months. The words apparently are used as genuine symbols and their number compares favorably to the number of words children use at the same chronological (though not the same developmental) age. Gardner and Gardner and their assistants address Washoe in sentences, much as parents address children in sentences, and Washoe has begun to combine signs into what Gardner and Gardner accept also as sentences. It is the process of combination, however, that shows a basic difference between children and Washoe. Unlike Adam or any other child Washoe combines words without restriction. The grammatical puritanism that hails the beginning of true syntax in children is thus utterly lacking in Washoe. The following are examples of (at some distance from a door) Washoe’s combinations (each English word corresponds to a deaf-mute sign):

In none of these utterances is the relation the same, with the exception of ‘ go in ’ and ‘ go out ’ - which unlike the others could be imitations. In ‘ open flower ’, for instance, the relation is movement toward something, whereas in ‘ open key ’ the relation is one of instrumentality. It is possible that Washoe actually draws such distinctions, in which event we should conclude that she is far in advance of children at a comparable length of utterance, but it is more probable that Washoe does not organize words into grammatical relations at all. She produces instead whatever signs are appropriate to her situation when she happens to know them, but successive signs are independent of each other. It is consistent with this interpretation that she does not produce signs in fixed order. She can, as Gardner and Gardner supposed, acquire words and she is not limited to uttering a single word at a time. But as far as these few examples reveal she cannot organize meanings in the particular ways routinely and universally available to children.

I have summarized, most briefly, a few reasons for supposing that the concept of a sentence is not a product of learning. It can be detected during the holophrastic period, before words have ever been put into combination, and even can be seen undergoing development at that time. It covers completely all instances of word combination, when these appear. And it fails to cover word combinations when the concept is not available for reasons of species specificity. The concept of a sentence apparently reflects specific abilities, presumably innate to man, which children possess as a necessary condition for the acquisition of language.

Faced with the prospect of crediting children with this balance of a priori structure a number of psycholinguists have felt an urge to explain it. Explanation is of course commendable. It is the ultimate goal of all of us. My argument merely is that certain basic distinctions cannot be overlooked if such explanations are to be found. It is worthwhile examining the situation closely. According to Schlesinger (in press) the underlying structure of sentences ‘ are determined by the innate cognitive capacity of the child. There is nothing specifically linguistic about this capacity.’ And Sinclair- deZwart (1970) has written that ‘ Linguistic universals exist precisely because thought structures are universal’. Both Schlesinger and Sinclair-deZwart are discussing the abstract linguistic structures referred to here as the concept of a sentence. The influence of cognition, in their view, is visible in the universal underlying structure of language.

Contrary to these claims, however, the abstract structure of sentences may equally reflect specific linguistic abilities. A distinction must be drawn between at least two kinds of linguistic universal. It is possible that further divisions will prove useful, which would move us even further from the monolithic situation implied by Schlesinger and Sinclair in the statements quoted above, but the following distinction will serve as a beginning:

Weak linguistic universals have a necessary and sufficient cause in one or more universals of cognition or perception.

Strong linguistic universals may have a necessary cause in cognition or perception, but because another purely linguistic ability also is necessary, cognition is not a sufficient cause.

This distinction is purely psychological. Linguistics has nothing to do with it. Linguistic theory, where it is postulated what is universal in language, gives no hint of the causes of linguistic universals. Consider, for example, the grammatical categories of nouns and verbs. They appear universally in the underlying structure of language because linguistic descriptions are universally impossible without them. According to the theory of language acquisition described earlier in this paper, they appear universally because children spontaneously organize sentences in terms of such categories. Now, in addition, we wish to explain this activity of children. If nouns and verbs are weak linguistic universals they have a necessary and sufficient cause in cognitive development. Most theories of cognition would provide something like the notions of actor, action, and recipient of action, as categories of intellectual functioning that are available to young children. One might argue that nouns and verbs are the reflection in language of these cognitive categories. If, however, nouns and verbs are strong universals, some further ability is necessary in addition to the cognitive categories of actor, action, and recipient of action. The latter may be necessary but they are not sufficient to cause the appearance of nouns and verbs in child grammar.

The essence of the strong-weak distinction is the psychological status of the linguistic terms ‘ noun ’ and ‘ verb ’. Do they refer to processes of cognition, which are given special names in the case of language, or do ‘ noun ’ and ‘ verb ’ refer also to specific linguistic processes, which have an independent ontogenesis? There is no way to prejudge this question; contrary to Sinclair and Schlesinger, there is no a priori answer. The only way to proceed is to raise the question for each linguistic universal in turn. A proper investigation, of course, would not always and necessarily lead to the same answer with every universal. It is conceivable that language is a mixture of weak and strong universals.

As an example of how the distinction between weak and strong universals can be approached, consider an observation reported by Braine (1970). He taught his two- and-a-half year old daughter two made-up words: the name of a kitchen utensil )niss) and the name of walking with the fingers )seb). The child had no word for either the object or the action before Braine taught her niss and seb. Neither word was used in a grammatical context by an adult, but the child used both in the appropriate places.

There were sentences using niss as a noun, such as that niss and my niss, and sentences using seb as a verb, such as more seb and seb Teddy. More important in the present context there were sentences also with seb as a noun, that seb and my seb, but none with niss as a verb. The asymmetry suggests that verbs are weak universals and nouns strong. Association with an action is necessary and sufficient for a word to be a verb but some additional linguistic property can make a word into a noun. Association with an action does not block the classification. The situation is not as perfect as we might like it, however, for association with an object may also be sufficient for a word to become a noun. If this is true, we should further subdivide linguistic universals into weak, strong, and ‘ erratic ’ types. An erractic universal is one in which a linguistic universal has two sufficient causes and therefore no necessary ones. Both the cognitive category of object and a linguistic ability can lead a word to become a noun.

I would argue that no progress can be made in the explanation of linguistic universals unless these basic distinctions are honored. Sweeping remarks, that all universals of language are in reality universals of cognition, cross the line separating science from dogma.

1 This paper is based on a paper entitled ‘Explaining linguistic universals’ in J. Morton (ed.), Biological and social factors in psycholinguistics. London: Logos Press, 1971.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)