Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

RANGE OF MEANING, AND N O N - UN I Q UENES S OF DEFINITIONS

المؤلف:

R. M. W. DIXON

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

453-25

2024-08-20

1191

RANGE OF MEANING, AND NON - UNIQUENESS OF DEFINITIONS

The situational realization of a nuclear verb will be approximately the sum of the situational realizations of its component features. But only approximately – each word also has its own character, its own special personality traits as it were, that mould from the meanings of the constituent features a distinctive concept. (It will thus be seen that semantic features are, to some extent, slightly idealized generalizations.)

Each word has a range of situational realisations.1 It may have some ‘central’ realization, and be then extended to cover situational phenomena that are situationally similar to the ‘central’ phenomenon. In this way the semantic system of a language can cover all relevant situational patterns, first focussing on ‘central ’ patterns and then extending outwards from these to cover the intermediate territory. ‘Ambiguous’ types of situational phenomena, that can be covered by extension from two different foci, say, may be the subject of taboo (see Douglas 1966, Leach 1964).2 Central phenomena seem, empirically, most likely to be concerned with aspects of humans and human behavior; phenomena relating to geographical features and happenings, and to artifacts, are often dealt with as extensions from central phenomena.

For instance, neither Dyirbal nor its neighbor language Mbabaram have any verbs whose central situational realization involves rain falling. Certain verbs are used to refer to rainfall (as a non-central part of their meaning) according as the action of rain falling seems situationally similar to the central situational realization of the verb. Dyirbal is spoken in an area of devastatingly heavy rainfall (150 in. per year) whereas the area in which Mbabaram is spoken, although only 50 miles distant, has a rainfall of only about 30 in. per year. Dyirbal has two verbs, both transitive, used to refer to rainfall: bidyin ‘ hit with a rounded object, e.g. punch, throw a stone at’ for the extremely heavy wet season storms, and dyindan ‘gently wave or bash, e.g. blaze bark, sharpen pencil ’ for the only moderately heavy storms throughout the rest of the year. Mbabaram, however, refers to rainfall exclusively through the intransitive verb aŋanuŋ ‘ fall down ’. The different types of rainfall in the two regions lead to situational analogies being established to quite different ‘human actions’, that are the central realizations of dissimilar verbs in the two languages.

The referential relation between a nuclear word and corresponding non-nuclear words appears to be of the same type as that between the central meaning of a word and its extensional meanings. First we have nuclear words, whose central situational realizations are as it were the ‘ major foci ’. Then non-nuclear words, whose central situational realizations are minor foci, each related to (that is, a defined extension from) some major focus. Now all situational phenomena can be described in terms of these major and minor foci; a point in situational space which is not itself a focus is treated as an extensional or peripheral realization of that word whose focus it is situationally most similar to.

For instance, two of the nuclear verbs in Dyirbal are bidyin ‘ hit with a rounded object’ and baygun ‘shake, wave or bash’. The componential semantic descriptions of these two verbs are (affect, strike, rounded object; tr) and (position, affect, motion, direction, hold on to; tr) respectively. There is a non-nuclear verb dyindan ‘ gently wave or bash ’ that is defined semantically in terms of the semantic description of baygun and the specification ‘with agent exercising full control over the action’ or something similar. The situational phenomenon of rain falling is not a major or minor focus - that is, it is not the central realization of any verb, nuclear or non-nuclear. The two different kinds of rainfall are, to the Dyirbal, most similar to the central realizations of nuclear bidyin and non-nuclear dyindan respectively, and reference to rainfall can thus be looked upon as secondary or extensional meanings of these two verbs.

We referred above to Leach’s and Douglas’s discussion of phenomena which have some degree of similarity to two different foci; such a phenomenon cannot be classified as clearly an extension from a single focus and may as a result be considered taboo. Something of the same sort applies for non-nuclear words, considered as ‘ extensions ’ of nuclear words (although in this case, of course, there is no taboo attached). A word may be clearly non-nuclear, but its reference may be as it were ‘ equidistant ’ from a number of major foci: that is, it can be adequately defined in several different ways, each in terms of a different nuclear word. The next two paragraphs illustrate this with Dyalquy data, involving first a non-nuclear Guwal verb, and then a noun.

The situational realization of the non-nuclear verb wirban ‘sweep ground with bramble stick or weed to clear away leaves ’ appears to be equally similar to several major foci. Three different mother-in-law correspondents were given at different times, involving three different nuclear verbs - Dyalŋuy wirŋganyu corresponding to Guwal nuclear verb gibanyu ‘scrape, trim’ with semantic description (affect, strike, sharp-bladed implement, low degree; tr); Dyalŋuy burganman, Guwal nuclear digun ‘ clear away, rake away, dig - using hands - on the surface ’, semantic description (position, affect, motion, place, from, here; tr); and Dyalŋuy nayŋun, Guwal nuclear madan ‘ throw ’, semantic description (position, affect, motion, direction, let go of; tr). Thus the assessment of similarity between the realization of wirban and some major focus picks on either the action of the bramble stick on the ground (in the ‘ scrape ’ case), or what the bramble stick does to the leaves (in the ‘ clear away ’ - i.e. move position away from here - case), or the way in which the stick does this to the leaves (in the ‘throw’ case). The action has in Guwal a single appropriate name, wirban, but in Dyalŋuy it can be described equally well by either wirŋganyu, burganman or nayŋun.

There are only around a quarter as many nouns describing types of trees in Dyalŋuy as in Guwal. One Dyalŋuy noun corresponds to three or four Guwal nouns, whose referents all have the same sort of grain, or the same type of sap, or the hardest wood, or can be used for making shields, or water-bottles, and so on. The seven Guwal nouns for trees bearing fruit that requires preparation (roasting, grinding, soaking, etc.) all have one-to-one Dyalŋuy correspondents. But there is a single Dyalŋuy noun, gumulam, for the two dozen or so Guwal nouns referring to trees whose fruit can be eaten raw. Now the moreton bay fig tree, magma in Guwal, has fruit that can be eaten raw, and so can be described as gumulam in Dyalŋuy. But shields are made from the wood of this tree and so it can also be called gigiba in Dyalŋuy, as can the slippery blue fig, Guwal milbir. Thus this type of tree has in Guwal, although an allative or locative verb marker to which they are bound can.

From our assumption that a one-to-one Guwal-Dyalŋuy correspondence implies a relation of synonymy between the words concerned, and the fact that verbalizer-bin does not change the semantic content of a word, but just marks it as an intransitive verbal, it follows that the semantic content of waynydyin must be the same as that of dayu, and so on. (That is, leaving aside the feature ‘ long way ’ in the semantic description of dayu: verbs of motion do not specify distance and in fact Dyalŋuy correspondents involve the unmarked feature from the system (long, medium, short distance}.)

Verbs markers can be described in terms of semantic features as follows:

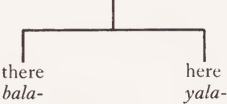

(1) a single system specifies ‘here’ or ‘there’ (there is no third ‘heard but not seen ’ feature for verb markers, as there is for noun markers):

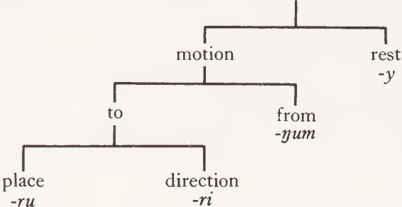

(2) a tree of systems specifies case inflections:

-ru and -ri are grouped together as ‘to’ since they (unlike ‘from’ and ‘at’) can cooccur with nouns and adjectives in allative inflection; ‘ to ’ and ‘ from ’ are grouped together, as ‘motion’, since one class of verbs normally occur only with motion markers, and another class normally occur only with rest markers.

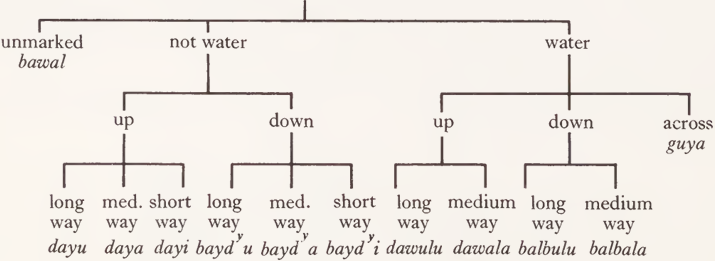

(3) bound forms -baydyi etc. can be described by the tree:3

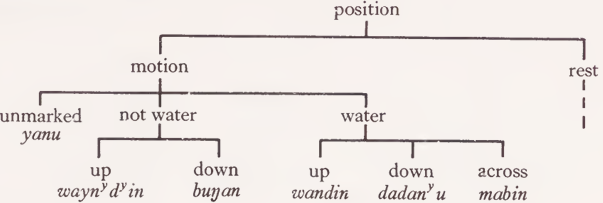

The fact that simple verbs concerned with position4 fall into two classes, ‘ motion ’ and ‘ rest ’, suggests that the semantic descriptions of these verbs should be taken to include the appropriate feature: ‘motion’ or ‘rest’. From this and the Dyalŋuy data we can generate semantic descriptions:

Verbs of ‘rest’ can be further distinguished through the widely-occurring - if not universal - system {stand, sit, lie}.5

We see that in the semantic descriptions of verb markers, the choice of a feature from the system {water, not water, unmarked} is independent of the choice made from system {motion, rest}. In the case of verbs, however, a feature from the system {water, not water, unmarked} can only be included in a semantic description together with the feature ‘ motion ’, and not with the feature ‘ rest ’. That is, there are verbs specifying ‘ whereness ’ of motion but not ‘ whereness ’ of rest; whereas verb markers can specify ‘ whereness ’ of both motion and rest.

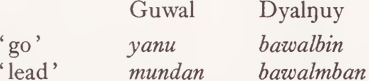

Looking now at the Dyalŋuy correspondents of yanu and mundan:

we see that we have the (non-causative) transitive verbalizer ~)m)ban, plus bawal, for mundan, as against intransitive verbalizer -bin plus bawal for yanu. This would suggest that yanu and mundan have the same semantic content, and differ only in that mundan belongs to the class of transitive verbs and yanu to that of intransitive verbs.

We have thus been able to provide semantic descriptions of a number of verbs of motion entirely in terms of (1) features from systems which underlie grammatical categories in Dyirbai, and (2) specification of transitivity.

Dyirbal verbs are very strictly categorized as transitive or intransitive; there are Definitions of non-nuclear verbs can either be (1) in terms of a single nuclear verb, or (2) in terms of two or more nuclear verbs, or (3) in terms of a verbalized noun or adjective. In some cases informants gave mother-in-law correspondences which only defined a part of the meaning of a non-nuclear verb; occasionally they had to resort to mime to complete the specification of a meaning.

(1) Definition in terms of a single nuclear verb, that receives some special modification or qualification, or some reassignment of syntactic functions.

(i) addition of a grammatical particle

Nuclear gayban ‘call’: Dyalŋuy correspondent mayban6

Non-nuclear ŋaɽin ‘answer’: ŋurinydyi mayban ‘call in turn’

(ii) reduplication (usually implying that the action is performed to excess)

Non-nuclear yadyan ‘speaker asks someone to accompany him’: bunman

Non-nuclear gurŋalman ‘speaker keeps on asking a person to accompany him when the person has already refused (the person being someone who is a friend of the speaker, and normally accompanies him) ’: bunmabunman

(iii) addition of an aspectual affix7 for instance -ganiy, implying that the event is repeated, at longish intervals

Nuclear midyun ‘take no notice of’: nyanydyun

Non-nuclear budyilmban ‘completely ignore (someone who is trying to attract one’s attention)’: nyanydyulganinyu

(iv) addition of a derivational affix:

(a) reflexive.

(b) reciprocal affix -(n)bariy (plus obligatory reduplication)

Nuclear wugan ‘give’: dyayman

Non-nuclear munydyan ‘ divide ’: dyaymaldyaymalbarinyu (lit ‘ give to each other ’)

(c) causative affix -m(b)al

Nuclear yilmbun ‘ pull, pull up ’: yilwun

Non-nuclear yiwulumban ‘pull branch down so that fruit can be pulled off it’: yilwulman

(v) addition of an adverbal

Nuclear verb bidyin ‘hit with rounded implement’: dyubumban

Nuclear adverbal ŋunin ‘start doing, try, test’: ŋuɽbin

Non-nuclear verb ɽuldyun ‘test by banging, e.g. bang the reverse of a tomahawk head on a log to test for hollowness ’: ŋuɽbin dyubumban

(vi) addition of locational specification

Nuclear mabin ‘cross river’: guyabin

Non-nuclear balŋgan ‘cross by walking on log thrown across river’: dalmbiɽaru guyabin

)dalmbir is the Dyalŋuy correspondent of Gusna yugu ‘tree, stick, log’.

The locative inflection is dalmbiɽa, and -ru is an additional suffix indicating motion, thus dalmbiɽaru ‘along a log’.)

(vii) addition of some specification of an NP in (subject or object) grammatical relation to the verb

(a) specification of NP head (Mamu dialect example)

Nuclear buŋgan ‘empty out, capsize’: yiyaban

Non-nuclear buybun ‘spit’: ŋudyuŋgu yiyaban

(Guwal nyumba ‘spittle’ has the Dyalŋuy correspondent ŋudyu; -ŋgu is the ergative/instrumental inflection.)

(b) specification of NP modifier - see bumiranyu

(c) specification of relative clause qualifying NP head

Nuclear dyuran ‘rub’: dyurmbayban

Non-nuclear yidyin ‘an aboriginal doctor rubbing a sick person (often using sweat from his armpits) to cure him ’: maŋgaybiŋu dyurmbayban (maŋgay is the Dyalŋuy correspondent of Guwal wuygi ‘no good’; thus intransitively verbalized maŋgaybin ‘feel ill’ from which is formed the relative clause maŋgaybiŋu ‘who feels ill’.)

(viii) reassignment of syntactic function.

For nuclear buwanyu ‘tell’ the subject is the teller and the object the person to whom the news is told; for non-nuclear dyinganyu the subject is again the teller but the object is what is being talked about (the person to whom it is told can, optionally, be included as indirect object). Both were given Dyalŋuy correspondent wuyuban in stage 1 of elicitation, and in stage 2 dyinganyu was further specified as wuyuwuyuban ‘tell to excess’. In this case Dyalŋuy exposes the difference in semantic content (‘tell some particular news or story') but not the difference in syntactic function (what is object and what indirect object).

(ix) addition of a semantic feature

In addition to the types of definition shown by Dyalŋuy correspondences, a non-nuclear Guwal verb can also be defined in terms of a nuclear verb plus a single semantic feature. In such cases Dyalŋuy correspondents cannot reflect the situation accurately: for instance, the semantic description of waban ‘look up’ is that of buɽan ‘look’ (C-equivalent of Dyalŋuy nyuɽiman) plus that of gala ‘up’; however nyuɽiman gala is not a permissible VP (since gala is a bound form that can only occur with a verb marker): informants gave nyuɽiman yalugalamban as Dyalŋuy correspondent of waban.

(2) Definition in terms of more than one nuclear verb. Some non-nuclear verbs can be regarded as expressing the logical intersection of two (or sometimes more) basic concepts, each of which corresponds to a single nuclear verb. For example, there are concepts ‘clear away’, Dyalŋuy burganban with Guwal C-equivalent digun; and ‘look at, look for, see’, Dyalŋuy nyuɽiman with Guwal C-equivalent buɽan. Guwal non-nuclear nuwan ‘sort through things searching for something - i.e. rummage’ is the intersection of these two concepts. A simple one-wrord Dyalŋuy correspondent cannot be given for nuwan since it is equally related to nyuɽiman and to burganban; in such cases normal Dyalŋuy elicitation procedure breaks down: an informant will give one Dyalŋuy word one time and the other another time, or else combine them, as burganban nyuɽimali ‘sort through in order to look’ (in fact a mark of such double-concept non-nuclear words is the unusual inconsistency of Dyalŋuy correspondents given for them). A further example is non-nuclear dyaymban ‘find’, which is the intersection of nuclear concepts buɽan ‘look at, look for, see’ and maŋgan ‘pick up’ (Dyalŋuy mulwan); and so on.8

(3) Definition in terms of a verbalized adjective or noun. Non-nuclear verb maban ‘set fire to; light fire or lamp’ was given Dyalŋuy correspondent ŋarganamban, the transitively verbalized form of Dyalŋuy noun ŋargana, itself the correspondent of Guwal nyaɽa ‘ flame ’ (thus maban is defined as ‘ make (become) a flame’).

Turning now to the few cases where Dyalŋuy does not provide a full (or fairly full) definition: it seems that some Guwal verbs cannot adequately be distinguished within Dyalŋuy as a meta-language. There are three possibilities here:

(1) The defining parameter distinguishing two verbs may not be describable (or not easily describable). Nuclear dyuran ‘ rub ’, non-nuclear baŋgan ‘ paint or draw with finger (and nowadays: write) ’ and non-nuclear nyamban ‘ paint with the flat of the hand’ were all given correspondent dyurmbayban in stage 1 of elicitation. But neither Guwal nor Dyalŋuy has a term for ‘finger’ as opposed to ‘hand’: Guwal mala, Dyalŋuy manbuɽu cover both meanings. Thus stage 2 elicitation was not able to specify ‘ finger as agent ’ for baŋgan, for instance; instead dyirinydyirinydyu dyurmbayban ‘rub with white clay’ was given (in fact white clay is almost always applied with the finger). Here, the defining characteristic could not be specified and so a secondary characteristic of the type of action (in this case, the material used) was specified. If a conversation in Dyalŋuy did try to describe the (unusual) application of white clay with the flat of the hand, mime would probably be resorted to.

(2) In some cases the full range of meaning of a Guwal verb is not specifiable in Dyalŋuy: different detailed Dyalŋuy correspondents have to be given according to the different specific meanings in instances of use. For example:

Nuclear ŋanban ‘ask’: Dyalŋuy baŋarmban

Non-nuclear nungan ‘speaker asks or encourages someone to assist him in doing something bad (e.g. fighting or stealing) ’: this can only be distinguished from ŋanban within Dyalŋuy by specifying a particular bad action, e.g. Dyalŋuy baŋarmban bagul duyilaygu ‘ ask to fight [a third man] ’; and so on.

(3) In some cases, words are only distinguishable in Dyalŋuy through an accompanying mime, or through some paralinguistic information. For example, in stage 1 elicitation gundumman ‘ bring together ’ was given for both nuclear bugaman ‘ chase, run down ’ and non-nuclear dyulman ‘ squeeze (and mix flour with ingredients in baking, etc.) ’. In stage 2 elicitation dyulman could only be distinguished in terms of gundumman yalaban together with a squeezing mime, made by grasping the hands together. (Dyalŋuy yalaban is the correspondent of Guwal yalaman ‘ do it like this’.) As another example, the Dyirbal informant gave burmbunyman as the Dyalŋuy correspondent of both nyundyan ‘kiss’ and buybun ‘spit at’; the informant was unable further to define either of these verbs within Dyalŋuy and when asked how one would distinguish in Dyalŋuy between ‘the man kissed the girl’ and ‘the man spat at the girl’ demonstrated different voice timbres that clearly set off the two sentences: a warm, inviting timbre for the ‘ kiss ’ sentence and a higher, harsher timbre for ‘ spit’.

1 For further discussion of ‘ range of meaning’ see McIntosh 1961, Nida 1964. Bloomfield (1933.149) uses the terms normal (or central) and marginal (metaphoric or transferred) meaning.

2 For instance, Leach (1964.40-2) mentions that speakers of English classify animals in certain ways, and on the basis of this linguistic classification decide what to eat and what not to eat. Leach considers the basic discrimination to rest in three words: (1) fish, creatures that live in water - this category is fairly elastic, including shell-fish; (2) birds, two-legged animals with wings that lay eggs (they need not necessarily fly); (3) beasts, four-legged mammals living on land All the creatures considered edible by us are fish, birds or beasts. There is a large residue (reptiles and insects) rated as not food by us, although rated as food by many other peoples. The hostile taboo is applied most strongly to creatures that are most anomalous in respect of the major categories, for example, snakes - land animals with no legs that lay eggs.

3 We can give phonological realizations for the features in the tree, and thus generate ten of these forms (the exceptions are bawal and guya). ‘ Up ’ is associated with phonological specification daS, ‘ down ’ with baLP, where S, P and L stand for ‘ semivowel ’, ‘ plosive ’ and ‘ linking consonant (after a vowel and before an intersyllabic nasal and/or plosive)’ respectively. ‘ Not water ’ is associated with a prosody of palatalization and ‘ water ’ with one of labialization; the prosodies extend over all segments not already fully specified, i.e. over S, P and L in the forms above. S plus palatalization is the segment y, S plus labialization is w. P plus palatalization is dy plus labialization is b. The linking consonant can be y, l, r or ɽ; L plus palatalization is y. There is no specifically bilabial linking consonant, so that L plus labialization specifies quite naturally the ‘ unmarked ’ linker /. Thus forms day-, daw-, baydy-, balb- are generated. ‘ Short ’, ‘medium ’ and ‘long distance are associated with -i, -a and -u respectively. (For a discussion of the extra affix -lu ~ -la on ‘ water ’ forms, of phonological marking, and of the full phonological structure of Dyirbal, see Dixon 1968 a.)

4 There is no obvious term to refer to both verbs of motion and verbs of rest; ‘ position * is used here as something that seems no worse than any other possibility.

5 The semantic description of yanu - but not those of waynydyin, buŋan, wandin, dadanyu and mabin- also involves the unmarked features ‘to’ and ‘there’, contrasting with the semantic description of baninyu ‘come’ which involves ‘to’ and ‘here’. The Dyalŋuy correspondent of baninyu is yalibin, i.e. the verbalized form of the ‘to (direction) here’ marker (and to keep Dyalŋuy different from Guwal, yali - unlike other verb markers bali, yalu, balu, yalay, balay - does not occur in intransitively verbalized form in Guwal).

6 Throughout these definitions, a Guwal verb is given on the left, and its Dyalŋuy definition on the right of the colon.

7 In the wide sense of ‘ aspectual ’ (here, covering all non-inflectional affixes that do not change the syntactic status of a stem); there are four such affixes in Dyirbal: -ganiy ‘event repeated at longish intervals’, -dyay ‘event repeated many times within short time span’, -yaray ‘start to do/do a bit more’ and -galiy ~ ~(n)bal ‘do quickly’. Informants gave definitions involving the first three of these affixes.

8 There is an important difference between these examples and the wirban example. Here the semantic description of the non-nuclear verb is exactly the logical intersection of two nuclear descriptions. Several different definitional descriptions could be given for wirban, each itself a full and adequate definition (and these definitions involve different nuclear verbs).

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)