Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Surface realization of arguments

المؤلف:

CHARLES J. FILLMORE

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

378-22

2024-08-12

984

Surface realization of arguments

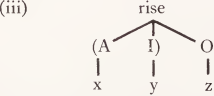

I suggested that the conceptually necessary arguments to a predicate cannot always be matched on a one-to-one basis with the ‘cases’ that are also associated with the same predicate. It may now be pointed out that there is also no exact correspondence between either of these and the number of obligatorily present syntactic constituents in expressions containing the predicates in question. Buy, as we have seen, is a four-argument (but five-case) predicate which can occur in syntactically complete sentences containing two, three or four noun phrases. Thus (40) :

(40) He bought it (from me) (for four dollars)

in which optionally present segments are marked off by parentheses.

The verb blame has associated with it three roles, the accuser (Source), the defendant (Goal), and the offense (Object).

Expressions with this verb can contain reference to all three, as in (41), just two,

as in (42) and (43), or only one, as in (44):

(41) The boys blamed the girls for the mess.

(42) The boys blamed the girls.

(43) The girls were blamed for the mess.

(44) The girls were blamed.

No sentence with blame, however, can mention only the accuser, only the offense, or just the accuser and the offense. See (45)—(47):

(45) *The boys blamed.

(46) *The mess was blamed.

(47) *The boys blamed (for) the mess.

An examination of (41)-(47) reveals that the case realized here as the girls is obligatory in all expressions containing this verb, and, importantly, that there are two distinct situations in which the speaker may be silent about one of the other arguments. I take sentence (43) as a syntactically complete sentence, in the sense that it can appropriately initiate a discourse (as long as the addressee knows who the girls are and what the mess is). In this case the speaker is merely being indefinite or non-committal about the identity of the accuser. I take sentence (42), however, as one which cannot initiate a conversation and one which is usable only in a context in which the addressee is in a position to know what it is that the girls are being blamed for. Another way of saying this is that (43) is a paraphrase of (43') and (42) is a paraphrase of (42'):

(42') The boys blamed the girls for it.

(43') The girls were blamed for the mess by someone.

This distinction can be further illustrated with uses of hit. In (48), a paraphrase of (48'), the speaker is merely being indefinite about the implement he used:

(48) I hit the dog.

(48') I hit the dog with something.

In (49), the paraphrase of (49'), the speaker expects the identity of the ‘target’ (Goal) to be already known by the addressee:

(49)The arrow hit.

(49') The arrow hit it.

The two situations correspond, in other words, to definite and indefinite pronominalization.

Sometimes an argument is obligatorily left out of the surface structure because it is subsumed as a part of the meaning of the predicate. This situation has been discussed in great detail by Jeffrey Gruber (see note a, p. 374, above) under the label ‘ incorporation ’. An example of a verb with an ‘ incorporated ’ Object is dine, which is conceptually the same as eat dinner but which does not tolerate a direct object.1

The verb doff has an incorporated Source. If I doff something, I remove it from my head, but there is no way of expressing the Source when this verb is used. There is no such sentence as (50):

(50) *He doffed his hat from his balding head.

There are other verbs that identify events which typically involve an entity of a fairly specific sort, so that to fail to mention the entity is to be understood as intending the usual situation. It is usually clear that an act of slapping is done with open hands, an act of kicking with legs and/or feet, an act of kissing with both lips; and the target of an act of spanking seldom needs to be made explicit. For these verbs, however, if the usually omitted item needs to be delimited or qualified in some way, the entity can be mentioned. Hence we find the modified noun-phrase acceptable in such sentences as (51)—)53):

(51) She slapped me with her left hand.a

(52) She kicked me with her bare foot.

(53) She kissed me with chocolate-smeared lips.

Lexical entries for predicate words, as we have seen, should represent information of the following kinds: (1) for certain predicates the nature of one or more of the arguments is taken as part of our understanding of the predicate word: for some of these the argument cannot be given any linguistic expression whatever; for others the argument is linguistically identified only if qualified or quantified in some not fully expected way; (2) for certain predicates, silence (‘zero’) can replace one of the argument-expressions just in case the speaker wishes to be indefinite or non-committal about the identity of the argument; and (3) for certain predicates, silence can replace one of the argument-expressions just in case the LS believes that the identity of the argument is already known by the LT.

1 One can, however, indicate the content of the meal in question, as in an expression like He dined on raisins.

2 At least in the case of slap, the action can be carried out with objects other than the usual one. Thus it is perfectly acceptable to say She slapped, me with a fish.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)