Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Case structure

المؤلف:

CHARLES J. FILLMORE

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

376-22

2024-08-12

1139

Case structure

I identified the separate arguments associated with the verb rob by referring to their roles as ‘culprit’, ‘loser’, and ‘loot’; in a similar way, I might have identified the three arguments associated with the verb criticize as ‘critic’, ‘offender’, and ‘offense’. It seems to me, however, that this sort of detail is unnecessary, and that what we need are abstractions from these specific role descriptions, abstractions which will allow us to recognize that certain elementary role notions recur in many situations, and which will allow us to acknowledge that differences in detail between partly similar roles are due to differences in the meanings of the associated verbs. Thus we can identify the culprit of rob and the critic of criticize with the more abstract role of Agent, and interpret the term Agent as referring, wherever it occurs, as the animate instigator of events referred to by the associated verb. Although there are many substantive difficulties in determining the role structure of given expressions, in general it seems to me that for the predicates provided in natural languages, the roles that their arguments play are taken from an inventory of role types fixed by grammatical theory. Since the most readily available terms for these roles are found in the literature of case theory, I have taken to referring to the roles as case relationships, or simple cases. The combination of cases that might be associated with a given predicate is the case structure of that predicate.

In addition to the apparently quite complex collection of complements that identify the limits and extents in space and time that are required by verbs of motion, location, duration, etc., the case notions that are most relevant to the subclassification of verb types include the following:

Agent (A), the instigator of the event

Counter-Agent (C), the force or resistance against which the action is carried out

Object (O), the entity that moves or changes or whose position or existence is in consideration

Result (R), the entity that comes into existence as a result of the action

Instrument (I), the stimulus or immediate physical cause of an event

Source (S), the place from which something moves

Goal (G), the place to which something moves

Experiencer (E), the entity which receives or accepts or experiences or undergoes the effect of an action (earlier called by me ‘ Dative ’).

It appears that there is sometimes a one-many relationship between an argument to a predicate and the roles that are associated with it. This can be phrased by saying either that some arguments simultaneously serve in more than one role, or that in some situations the arguments in different roles must (or may) be identical.

Thus verbs like rise and move can be used intransitively, that is with one noun-phrase complement; the complement may refer just to the thing which is moving upward, or it may simultaneously refer to the being responsible for such motion. Thus in speaking simply of the upward motion of smoke we can say (30):

(30) The smoke rose

and in speaking of John’s getting up on his own power, we can say (31):

(31) John rose.

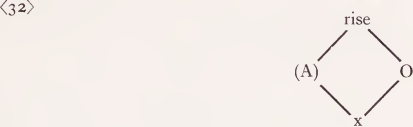

The case structure of rise, then, might be represented diagrammatically as <32):

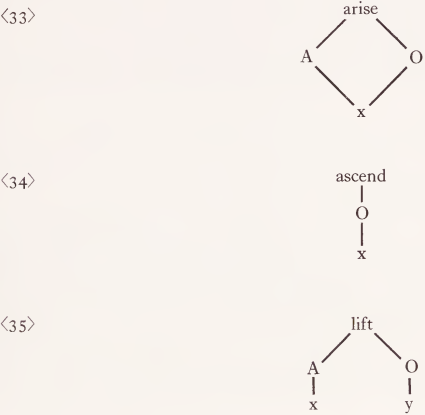

The fact that there are two case lines connecting rise with its one argument, and that the line labelled A has its case label in parentheses, reflect the fact that the argument can serve in just one of these roles (O) or simultaneously in both (A and O). Rise differs from arise in the optionality of A; it differs from ascend in having an ‘A’ line at all, and they all differ from lift in that the latter requires two arguments.1 Thus (33)-(35):

Frequently a linguistically codable event is one which in fact allows more than one individual to be actively or agentively involved. In any given linguistic expression of such an event, however, the Agent role can only be associated with one of these. In such pairs as buy and sell or teach and learn we have a Source (of goods or knowledge) and a Goal. When the Source is simultaneously the Agent, one uses sell and teach; when the Goal is simultaneously the Agent, we use buy and learn.

It is not true, in other words, that buy and sell, teach and learn are simply synonymous verbs that differ from each other in the order in which the arguments are mentioned.2 There is synonomy in the basic meanings of the verbs (as descriptions of events), but a fact that might be overlooked is that each of these verbs emphasizes the contribution to the event of one of the participants. Since the roles are different, this difference is reflected in the ways in which the actions of different participants in the same event can be qualified. Thus we can say (36):

(36) He bought it with silver money

but not (37):

(37) *He sold it with silver money.

Similarly, the adverbs in (38) and (39) do not further describe the activity as a whole, but only one person’s end of it :

(38) He sells eggs very skilfully.

(39) He buys eggs very skilfully.

1 In truth, however, lift also requires conceptually the notion of Instrument. That is, lifting requires the use of something (perhaps the Agent’s hand) to make something go up. It is conceivable that the basic case structures of arise and lift are identical, with grammatical requirements on identity and deletion accounting for their differences. Thus the two are shown in (i) and (ii):

For arise, however, it is required that x = y = z, and hence only one noun will show up. The meaning expressed by John arose is that John willed his getting up, that he used his own body (i.e., its muscles) in getting up, and that it was his body that rose. For lift, however, there may be identities between x and z, resulting in a sentence like John lifted himself, or there may be identities between y and z, resulting in a sentence like John lifted his finger. Rise, then, must be described as (iii):

where the identity requirements of arise obtain just in case x and y are present.

2 This has, of course, been suggested in a great many writings on semantic theory; most recently, perhaps, in the exchanges between J. F. Staal and Yehoshua Bar-Hillel in Foundations of Language, 1967 and 1968.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)