Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Two syntactic paradigms

المؤلف:

PAUL KIPARSKY AND CAROL KIPARSKY

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

345-21

2024-08-09

1214

Two syntactic paradigms

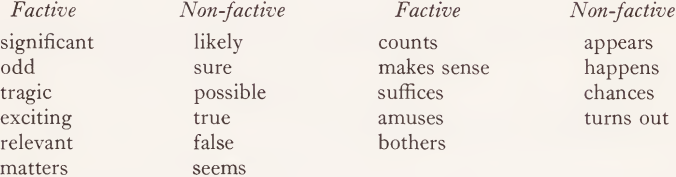

The following two lists both contain predicates which take sentences as their subjects. For reasons that will become apparent in a moment, we term them factive and non-factive.

We shall be concerned with the differences in structure between sentences constructed with factive and non-factive predicates, e.g.

Factive: It is significant that he has been found guilty

Non-factive: It is likely that he has been found guilty.

On the surface, the two seem to be identically constructed. But as soon as we replace the that-clauses by other kinds of expressions, a series of systematic differences between the factive and non-factive predicates beings to appear.

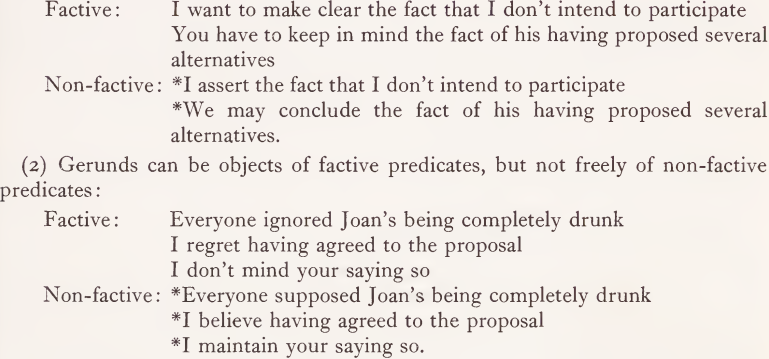

(1) Only factive predicates allow the noun fact with a sentential complement consisting of a that-clause or a gerund to replace the simple that-clause. For example,

The fact that the dog barked during the night

The fact of the dog’s barking during the night

can be continued by the factive predicates is significant, bothers me, but not by the non-factive predicates is likely, seems to me.

(2) Only factive predicates allow the full range of gerundial constructions, and adjectival nominalizations in -ness, to stand in place of the that-clause. For example, the expressions

His being found guilty

John’s having died of cancer last week

Their suddenly insisting on very detailed reports

The whiteness of the whale

can be subjects of factive predicates such as is tragic, makes sense, suffices, but not of non-factive predicates such as is sure, seems, turns out.

(3) On the other hand, there are constructions which are permissible only with non-factive predicates. One such construction is obtained by turning the initial noun phrase of the subordinate clause into the subject of the main clause, and converting the remainder of the subordinate clause into an infinitive phrase. This operation converts structures of the form

It is likely that he will accomplish even more

It seems that there has been a snowstorm

into structures of the form

He is likely to accomplish even more

There seems to have been a snowstorm.

We can do this with many non-factive predicates, although some, like possible, are exceptions:

It is possible that he will accomplish even more

*He is possible to accomplish even more.

However, none of the factive predicates can ever be used so:

*He is relevant to accomplish even more

*There is tragic to have been a snowstorm.

(4) For the verbs in the factive group, extraposition1 is optional, whereas it is obligatory for the verbs in the non-factive group. For example, the following two sentences are optional variants:

That there are porcupines in our basement makes sense to me

It makes sense to me that there are porcupines in our basement.

But in the corresponding non-factive case the sentence with the initial that-clause is ungrammatical:

*That there are porcupines in our basement seems to me

It seems to me that there are porcupines in our basement.

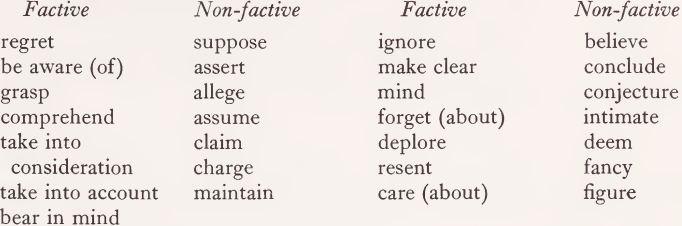

In the much more complex domain of object clauses, these syntactic criteria, and many additional ones, effect a similar division into factive and non-factive predicates. The following lists contain predicates of these two types:

(1) Only factive predicates can have as their objects the noun fact with a gerund or that-clause:

The gerunds relevant here are what Lees (i960) has termed ‘factive nominals’. They occur freely both in the present tense and in the past tense (having -en). They take direct accusative objects, and all kinds of adverbs and they occur without any identity restriction on their subject.2 Other, non-factive, types of gerunds are subject to one or more of these restrictions. One type refers to actions or events:

He avoided getting caught

*He avoided having got caught

*He avoided John’s getting caught.

Gerunds also serve as substitutes for infinitives after prepositions:

I plan to enter the primary

I plan on entering the primary

*I plan on having entered the primary last week.

Such gerunds are not at all restricted to factive predicates.

(3) Only non-factive predicates allow the accusative and infinitive construction:

Non-factive: I believe Mary to have been the one who did it

He fancies himself to be an expert in pottery

I supposed there to have been a mistake somewhere

Factive: *I resent Mary to have been the one who did it

*He comprehends himself to be an expert in pottery

*I took into consideration there to have been a mistake somewhere.

As we earlier found in the case of subject complements, the infinitive construction is excluded, for no apparent reason, even with some non-factive predicates, e.g. charge. There is, furthermore, considerable variation from one speaker to another as to which predicates permit the accusative and infinitive construction, a fact which may be connected with its fairly bookish flavor. What is significant, however, is that the accusative and infinitive is not used with factive predicates.

1 Extraposition is a term introduced by Jespersen for the placement of a complement at the end of a sentence. For recent transformational discussion of the complexities of this rule, see Ross (1967).

2 There is, however, one limitation on subjects of factive gerunds:

*It’s surprising me that he succeeded dismayed John

*There’s being a nut loose disgruntles me.

The restriction is that clauses cannot be subjects of gerunds, and the gerund formation rule precedes extraposition and there-insertion.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)