Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Form of syntactic markers

المؤلف:

URIEL WEINREICH

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

312-18

2024-08-06

1370

Form of syntactic markers

The theoretical status of the syntactic markers in KF is not clear. It is probably fair to understand that the function of the syntactic marker SxMi is to assure that all entries having that marker, and only those, can be introduced1 into the points of a syntactic frame identified by the category symbol SxMi. In that case the set of syntactic markers of a dictionary would be just the set of terminal category symbols, or lexical categories (in the sense of Chomsky 1965), of a given grammar.

It is implied in KF that this set of categories is given to the lexicographer by the grammarian. Actually, no complete grammar meeting these requirements has ever been written; on the contrary, since KF was published, a surfeit of arbitrary decisions in grammatical analysis has led syntactic theorists (including Katz) to explore an integrated theory of descriptions in which the semantic component is searched for motivations in setting up syntactic subcategories (Katz and Postal 1964; Chomsky 1965). But before we can deal with the substantive questions of justifying particular syntactic features, we ought to consider some issues of presentation - issues relating to the form of these features.

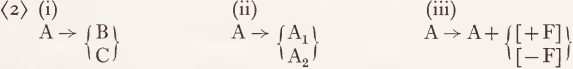

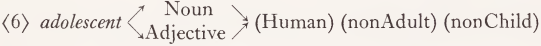

In general, the size and number of lexical categories (traditionally, parts-of-speech) depends on the depth or ‘ delicacy ’ of the syntactic subcategorization. (The term ‘delicacy’ is due to Halliday 1961.) Suppose a category A is subcategorized into B and C. This may be shown superficially by a formula such as (2i); a Latin example would be ‘Declinable’ subcategorized into ‘Noun’ and ‘Adjective’. However, the specific fact of subcategorization is not itself exhibited here. It would be explicitly shown by either (2 ii) or (2 iii). In (2ii), A1 = B and A2 = C ; in (2 iii) [+ F] and [ - F] represent values of a variable feature2 which differentiates the species B and C of the genus A. (An example would be ‘ Nomen ’ subcategorized into ‘ Nomen substantivum’ and ‘Nomen adjectivum’.) The feature notation has been developed in phonology and has recently been applied to syntax by Chomsky (1965).3

Single, global syntactic markers would correspond to implicit notations, such as (2i); sequences of elementary markers, to a feature notation such as {2 iii). The KF approach is eclectic on this point. The sequence of markers ‘ Verb → Verb transitive ’ for their sample entry play corresponds to principle (2iii); the marker ‘Noun concrete ’ seems to follow the least revealing principle, (2 i).4 To be sure, the examples in KF are intended to be only approximate, but they are surprisingly anecdotal in relation to the state of our knowledge of English syntax; what is more, they are mutually inconsistent.

A revealing notation for syntax clearly has little use for global categories, and we may expect that for the syntactic markers of dictionary entries in normal form, too, only a feature notation would be useful. In our further discussion, we will assume that on reconsideration KF would have replaced all syntactic markers by sequences expressing subcategorization.

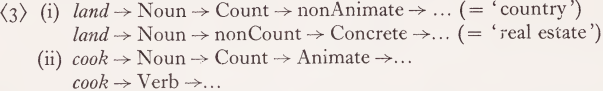

Suppose, then, we conceive of a syntactic marker as of a sequence of symbols (the first being a category symbol and the others, feature symbols). Suppose the dictionary contains entries consisting of partly similar strings, e.g. (3):

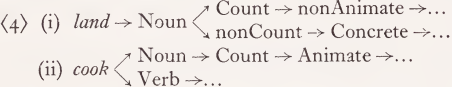

This partial similarity could be shown explicitly as a branching sequence, as in (4):

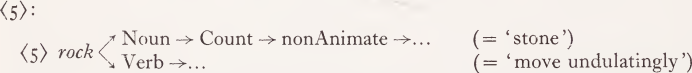

But this notation, proposed by KF, does not discriminate between fortuitous homonymy and lexicologically interesting polysemy, for it would also produce entries like

KF would therefore have to be extended at least by a requirement that conflated entries with branching of syntactic markers be permitted only if there is a reconvergence of paths at some semantic marker; only, that is, if the dictionary entry shows explicitly that the meanings of the entries are related as in (6).5 But such

makeshift remedies, feasible though they are, would still fail to represent class shifting of the type to explore - an explore, a package - to package as a (partly) productive process: the KF dictionary would have to store all forms which the speakers of the language can form at will. We return to a theory capable of representing this ability adequately.

1 By a rewrite rule, according to early generative grammar (e.g. Lees i960), or by a substitution transformation according to Chomsky (1965).

2 A feature symbol differs from a category symbol in that it does not by itself dominate any segment of a surface string under any derivation; in other words, it is never represented by a distinct phonic segment.

3 I am informed by Chomsky that the idea of using features was first proposed by G. H. Matthews about 1957, and was independently worked out to some extent by Robert P. Stockwell and his students.

4 We interpret ‘Noun concrete’ as a global marker since it is not shown to be analyzed out of a marker ‘Noun’.

5 Even so, there are serious problems in specifying that the point of reconvergence be sufficiently Bow’, i.e. that file ‘record container* and file ‘abrading instrument’, for example, are mere hononyms even though both perhaps share a semantic marker (Physical Object). This important problem is not faced in KF, even though the examples there are all of the significant kind (polysemy). See Weinreich (1963a: 143) for additional comments.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)