Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

LINGUISTICS

المؤلف:

HOWARD MACLAY

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

157-13

2024-07-17

1231

LINGUISTICS

It must seem perfectly obvious to the ordinary speaker of the language that meaning is a central and crucial element in his linguistic activity and that no account of his language which ignores this vital factor can possibly be adequate. While most scientific linguists also have acknowledged in passing the general importance of the semantic aspect of language, meaning has come to be widely regarded as a legitimate object of systematic linguistic interest only within the past decade. A collection of papers such as this one would have hardly been conceivable in the mid 1950s. In fact, most linguists of that period tended to regard a concern with meaning as evidence of a certain soft-headedness and lack of genuine scientific commitment. That this anthology is now available signals a significant shift in the prevailing conception of the goals and content of a valid linguistic description. In order to evaluate the essays which follow it is necessary to consider some of the attitudes toward meaning which have characterized the two dominant American schools of descriptive linguistics.1

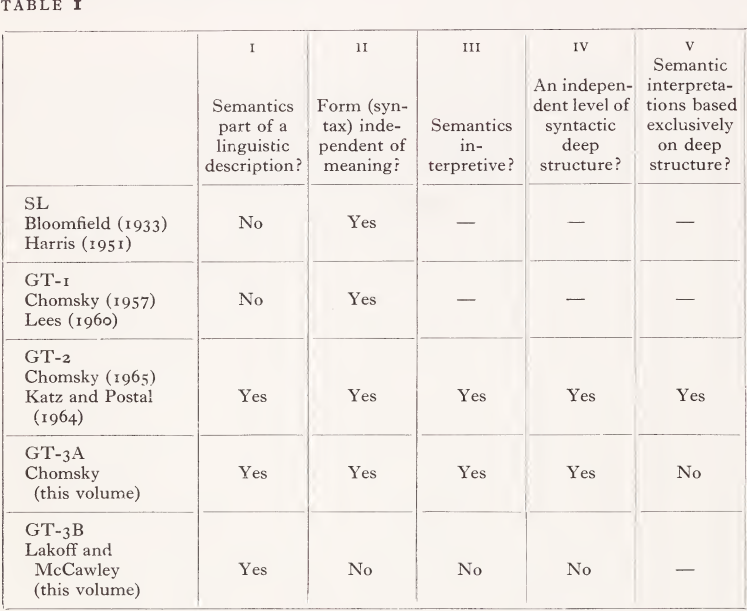

Although all of the papers either proceed directly from the assumptions of generative-transformational grammar or have been markedly influenced by this approach, they represent different tendencies within this framework, and they also differ in some important respects both from earlier transformational work and from studies based on a structuralist approach. Table 1 is an attempt to summarize, along a number of relevant dimensions, the central tendencies with regard to semantics characteristic of American structural linguistics and of four varieties of generative-transformational linguists. Figures 1-5 present diagrammatic representations of the interrelations among the components of a linguistic description as defined by each of these five approaches. These should be regarded as visual aids for the discussion to follow rather than as any sort of definitive account of the views of these schools.2

I will first describe the general organization of the analysis and then consider in more detail the content of each position. The discussion will attempt to present a simplified description of each position, omitting many details. Readers may consult the references for a more complete and adequate account.

The entries of Table 1 are organized in chronological order with the numbers following each ofthe transformational positions indicating temporal order within this school (i.e. GT-3A and GT-3B are contemporaneous). A number of representative works are listed under each category and their dates provide a more precise index of the chronology involved. The fact that several of the items at the GT-3 level are included in this volume shows the very recent occurrence of this split in transformational theory.

The dimensions are presented in order of importance from left to right. They are at least partially independent in that a score on any one of them does not necessarily predict with complete accuracy the score on any other. Indeed, it is the various dependencies of fact and principle among dimensions that are most relevant in understanding these approaches to semantics. Dimension I simply asks whether or not meaning is to be regarded as a proper object of systematic linguistic analysis. If this is denied, on whatever grounds, then the score on Dimension II (Is syntax/ form independent of semantics?) is determined, since a grammar must be seen as confined to formal syntax (and, perhaps, phonology) which is, necessarily, independent of semantic considerations. If, however, it is argued that meaning is a proper part of a linguistic description, it is possible either to affirm or deny the independence of syntax. Dimension III (Is semantics interpretive?) is relevant only if a positive response has been given on Dimension 1. Given that meaning must be included and that syntax is independent of it, one can argue that semantics is interpretive (i.e. that the semantic component of a grammar must have syntactic information as input as in GT-2 and GT-3A) or, conversely, that the reverse condition exists. If the relevance of meaning i9 affirmed and the autonomy of syntax denied (GT-3B) then there is no reasonable sense in which one of the factors can be said to dominate the other. While the generative semanticists have surely moved semantics into a central role in linguistics this has involved the denial of a clear syntax/semantics distinction rather than an inversion of the relationship. Dimension IV (Is there an independent level of syntactic deep structure?) applies directly only to GT-2, GT-3A and GT-3B. It is factually redundant with respect to Dimension in for these theories, but there seems no necessary reason why one could not propose that the independent syntactic component of grammar be organized without this distinction. That the linguists of GT-3B would deny this division follows from their rejection of independent syntax and interpretive semantics. The final dimension (v) functions to distinguish between GT-2 and GT-3A and involves the question of which part or parts of the syntactic component provide the information necessary for semantic interpretation.

1 There seems little point in merely presenting a concise abstract of each paper in an introductory essay of this sort. Rather, an attempt will be made to provide a relevant context within which readers may arrive at their own evaluations.

2 Readers should be particularly wary of the directionality of the arrows in these diagrams as this is an issue of much dispute in linguistics at the present time. See the papers by Chomsky and Lakoff in this volume for further discussion. I believe the representations given here reflect accurately the practice of linguists at each period regardless of the ultimate logical relationship among the components of a grammar. In any case, most of them are based on published diagrams.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)