Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Singular terms

المؤلف:

ZENO VENDLER

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

115-10

2024-07-17

1407

Singular terms1

1 The attempt to understand the nature of singular terms has been one of the permanent preoccupations of analytic philosophy, and the theory of descriptions is often mentioned as perhaps the most obvious triumph of that philosophy. As we read the many pages that Russell, Quine, Geach, Strawson, and others have devoted to this topic, and as we follow them in tracing the problems it raises, we cannot but agree with this concern. Perhaps the most important use of language is the stating of facts, and in order to understand this role one has to know how proper names function and what constitutes a definite description, one has to be clear about what we do when we refer to something, in particular whether in doing so we assert or only presuppose the existence of a thing, and, finally, one has to know what kind of existence is involved in the various situations.

As I have just implied, the collective effort of the philosophers in this case has been successful. In spite of some disagreements the results fundamentally converge and give us a fairly illuminating picture of the linguistic make-up and logical status of singular terms. This is a surprising fact. My expression of surprise, however, is intended as a tribute rather than an insult: I am amazed at how much these authors have got out of the precious little at their disposal. A few and often incorrect linguistic data obscured by an archaic grammar were more often than not all they had to start with. Yet their conclusions, as we shall see, anticipate in substance the findings of the advanced grammatical theory of today. Of course, they had their intuitions and the apparatus of formal logic. But the former often mislead and the latter tends to oversimplify. In this case the combination produced happy results, many of which will be confirmed in this paper on the basis of strictly linguistic considerations.

2 I intend to proceed in an expository rather than polemical fashion. To begin with, I shall try to indicate the importance of singular terms for logical theory; then I shall outline the linguistic features marking such terms; and finally I shall use these results to assess the validity of certain philosophical claims.

Some philosophers regard terms as purely linguistic entities - that is, as parts of sentences or logical formulae - while others consider them as elements of certain nonlinguistic entities called propositions.2 Since my concern, at least at the beginning, is primarily linguistic, I shall use the word term in accordance with the first alternative, that is, to denote a string of words of a certain type or its equivalent in logical notation. This procedure, however, is not intended to prejudice the issue. We shall be led, in fact, by the natural course of our investigations, to a view some what different from the first alternative.

3 The word term belongs to the logician’s and not to the linguist’s vocabulary. Although the use of term is not quite uniform, most logicians would agree with the following approximation. The result of the logical analysis of a proposition consists of the logical form and of the terms that fit into this form. These latter have no structure of their own; they are ‘ atomic ’ elements, being, as it were, the parameters in the logical equation. But this simplicity is relative: it may happen that a term left intact at a certain level of analysis will require further resolution at a more advanced level. Russell’s analysis of definite descriptions and Quine’s elimination of singular terms can serve as classic examples of such a move.3 To give a simpler illustration, while in the argument

All philistines hated Socrates

Some Athenians were philistines

.'.Some Athenians hated Socrates

the expression hated Socrates need not be analyzed, that is, may be regarded as one term for the purposes of syllogistic logic, in the equally valid argument

All philistines hated Socrates

Socrates was an Athenian

.'.Some Athenian was hated by all philistines

the expression hated Socrates has to be split to show validity by means of the theory of quantification.

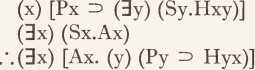

The logical forms available to simple syllogistic logic treat all terms in a uniform fashion: any term can have universal or particular ‘ quantity ’ depending upon the quantifier (all, some), the ‘ quality ’ of the proposition (affirmative or negative), and the position of the term (subject or predicate). It is in the theory of quantification that the distinction between singular and general terms becomes explicit. For one thing, the schemata themselves may provide for such a distinction. Consider the second argument given above. It can be represented as follows:

Notice that the argument will not work if Socrates is treated like the other terms (philistine, hated, Athenian). Such a treatment might amount to the following:

This argument, of course, is not valid. Nevertheless, as Quine stipulated, Socrates may be represented as a term on par with the rest," provided a uniqueness clause is added to the premises, that is

Quine’s proposal thus restores the homogeneity of terms characteristic of syllogistic logic: singularity or generality becomes a function of the logical form alone. Yet, in any case, whether the logician is inclined to follow Quine or not, he at least has to realize the difference between terms like Socrates and terms like philistine or Athenian, and must either represent the former by an individual constant or, if he prefers homogeneity and treats it as a predicate, then add the uniqueness clause. Then the question arises how to recognize terms that require such a special consideration, in a word, how to recognize singular terms. The possibility of an ‘ ideal ’ language without such terms will not excuse the logician from facing this problem if he intends to use his system to interpret propositions formulated in a natural language.

The linguistic considerations relevant to the solution of this problem are by no means restricted to the morphology of the term in question; often the whole sentence, together with its transforms or even its textual and pragmatic environment must also be considered. Granted, a logician who is a fluent speaker of the language is usually able to make a decision without explicit knowledge of the relevant factors. Such an intuition, however, cannot be used to support philosophical claims about singular terms with any authority. To provide such support and to make our intuitions explicit one has to review the ‘ natural history ’ of singular terms in English, to which task I shall address myself.

4 It is not an accident that in giving an example of a singular term I selected a proper name, Socrates; proper names are traditionally regarded as paradigms of singular terms. Owing to a fortunate convention of modern English spelling, proper names, when written, wear their credentials on their sleeves. This, however, is hardly a criterion. Many adjectives, like English, have to be capitalized too. Moreover, while this convention might aid the reader, it certainly does not help, in the absence of a capitalization morpheme, the listener or the writer. Thus we had better remind ourselves of the linguists’ dictum that language is the spoken language, and look for some real marks.

First we might fall back on the intuition that proper names have no meaning (in the sense of ‘ sense ’ and not of ‘ reference ’), which is borne out by the fact that they do not require translation into another language. Vienna is the English version and not the English translation of the German name Wien. Accordingly, dictionaries do not list proper names; knowledge of proper names does not belong to the knowledge of a language. In linguistic terms this intuition amounts to the following: proper names have no specific co-occurrence restrictions.4 A simple example will illustrate this.

(1) I visited Providence

is a correct sentence, but

(2) *1 visited providence

is not (here I make use of the above-mentioned convention). The word providence has fairly strict co-occurrence restrictions, which exclude contexts like (2). The morphologically identical name in (1), however, waives these restrictions and permits to co-occurrence with I visited. . . Of course, our knowledge that Providence is, in fact, a city will impose other restrictions. This piece of knowledge, however, belongs to geography and not linguistics. That is to say, while it belongs to the understanding of the word providence that it cannot occur in sentence like (2), it is not the understanding of the name Providence that permits (1), but the knowledge that it happens to be the name of a city. From a linguistic point of view, proper names have no restrictions of occurrence beyond the broad grammatical constraints governing noun phrases in general. Indeed, only some proper names show a morphological identity with significant words; and this coincidence is of a mere historical interest: Providence, as a name, is no more significant than Pawtucket. For these reasons some linguists regard all proper names as a single morpheme. The naming of cats may be a difficult matter, but it does not enrich the language.

A little reflection will show that the very incomprehensibility of the proper names that do not coincide morphologically with significant words, and the absence of specific co-occurrence restrictions with those that do, form a valuable clue in recognizing proper names in spoken discourse. But this mark applies to proper names only and casts little light in general on the nature of singular terms, most of which are not proper names. There are, however, other characteristics marking the occurrence of proper names that will lead us to the very essence of singular terms.

5 Names, as I implied above, fit into noun-phrase slots. And most of them can occur there without any additional apparatus, unlike the vast majority of common nouns, which, at least in the singular, require an article or its equivalent. The sentence

*1 visited city

lacks an article, but (1) above does not. Some common nouns, too, can occur without an article. This is true of the so-called ‘mass’ nouns and ‘abstract’ nouns. For instance:

I drink water.

Love is a many-splendored thing.

Yet these nouns, too, can take the definite article, at least when accompanied by certain ‘adjuncts’ (italicized) in the same noun phrase:5

I see the water in the glass.

The love she felt for him was great.6

Later on I shall elaborate on the role of adjuncts like in the glass and she felt for him. For the time being I merely express the intuition that these adjuncts, in some sense or other, restrict the application of the nouns in question; in the glass indicates a definite bulk of water, she felt for him individuates love.

This intuition gains in force as we note that such adjuncts and the definite article are repugnant to proper names, or, if we force the issue, they destroy the very nature of such names. First of all, there is something unusual about noun phrases like

{3) the Joe in our house

(4) the Margaret you see.

And, notice, this oddity is not due to co-occurrence restrictions:

(5) Joe is in our house

(6) You see Margaret

are perfectly natural sentences. The point is that while sentences like

I see a man

Water is in the glass

He feels hatred

yield noun phrases like

the man I see

the water in the glass

the hatred he feels

sentences like (5) and (6) only reluctantly yield phrases like (3) and (4). Nevertheless such phrases do occur and we understand them. It is clear, however, that such a context is fatal to the name as a proper name, at least for the discourse in which it occurs. The full context, explicit or implicit, will be of the following sort:

The Joe in our house is not the one you are talking about.

The Margaret you see is a guest, the Margaret I mentioned is my sister.

As the noun replacer, one, in the first sentence makes abundantly clear, the names here simulate the status of a count noun: there are two Joes and two Margarets presupposed in the discourse, and this is, of course, inconsistent with the idea of a logically proper name. Joe and Margaret are here really equivalent to something like person called Joe or person called Margaret, and because these phrases fit many individuals, they should be treated as general terms by the logician.

Certain names, moreover, can be used to function as count nouns in a less trivial sense:

Joe is not a Shakespeare.

Amsterdam is the Venice of the North.

These little Napoleons caused the trouble in Paraguay.

Here again we can rely upon the grammatical setting to recognize them as count nouns, albeit of a peculiar ancestry.

It is harder to deal with another case of proper names with restrictive adjunct and article. I do not want to claim that the names in sentences like

The Providence you know is no more

You will see a revived Boston

He prefers the early Mozart

have ceased to be proper names. Still less would I cast doubt on the credentials of proper names that seem to require the definite article, like the Hudson, the Bronx, the Cambrian, and so forth. The difficulties posed by these two kinds require more advanced linguistic considerations, so I shall deal with them at a later stage.

Disregarding such peripheral exceptions, we may conclude that proper names are like mass nouns in refusing the indefinite article, but are unlike them in refusing the definite article as well. And the reason seems to be that while even mass nouns or abstract nouns can take the when accompanied by certain restrictive adjuncts, proper names cannot take the since such adjuncts themselves are incompatible with proper names. Clearly, then, the intuitive notion that a proper name, as such, uniquely refers to one and only one individual has the impossibility of restrictive adjuncts as a linguistic counterpart. To put it bluntly, what is restricted to one cannot be further restricted. A proper name, therefore, is a noun which has no specific cooccurrence restrictions and which precludes restrictive adjuncts and, consequently, articles of any kind in the same noun phrase.

6 This latter point receives a beautiful confirmation as we turn our attention to a small class of other nouns that are also taken to be uniquely referring. These are the pronouns, I, you, he, she, and it.7 The impossibility of adding restrictive adjuncts and the definite article is even more marked here than in the case of proper names. Yet, once more, this is not due to co-occurrence restrictions; there is nothing wrong with sentences such as

I am in the room.

I see you.

But they will not yield the noun phrases

*(the) I in the room

*(the) you I see

which they would yield were the pronouns replaced by common nouns like a man or water. There is an even more striking point. Neither these pronouns nor proper names can ordinarily take prenominal adjectives. From the sentences

He is bald

She is dirty

we cannot get

*bald he

*dirty she.

And even from

Joe is bald

Margaret is dirty

we need poetic licence to obtain

bald Joe

dirty Margaret.

True, we use ‘Homeric’ epithets, like

lightfooted Achilles

tiny Alice

and, in an emotive tone, we say things like

poor Joe

or even

poor she

miserable you

but such a pattern is neither common nor universally productive. These facts seem to suggest that prenominal adjectives are also restrictive adjuncts. Later on we shall be able to confirm this impression.

7 ‘ A grammar book of a language is, in part, a treatise on the different styles of introduction of terms into remarks by means of expressions of that language.’8 Adopting for a moment Strawson’s terminology, we can say that proper names and singular pronouns introduce singular terms by themselves without any specific style or additional linguistic apparatus. These nouns are, in fact, allergic to the restrictive apparatus which other nouns need to introduce singular terms, or, reverting to our own way of talking, the restrictive apparatus which other nouns need to become singular terms. I shall take up the task of the grammar book and investigate in detail the natural history of singular terms formed out of common nouns. My paradigms will be count-nouns, simply because they show the full scope of the restrictive apparatus of the language.

It does not require much grammatical sophistication to detect the main categories of singular terms formed out of common nouns. They will begin with a demonstrative pronoun, possessive pronoun, or the definite article - for instance, this table, your house, the dog. The first two kinds may be identifying by themselves, but not the third. This can be shown in a simple example. Someone says,

A house has burned down.

We ask,

Which house?

The answers

That house

Your house

may be sufficient in a given situation. The simple answer

The house

is not. The alone is not enough. We have to add an adjunct that lends identifying force - for instance:

The house you sold yesterday

The house in which we lived last year.

Nevertheless, in certain contexts the alone seems to identify. Consider the following sequence:

I saw a man. The man wore a hat.

Obviously, the man I saw wore a hat. The, here, indicates a deleted but recoverable restrictive adjunct based upon a previous occurrence of the same noun in an identifying context. This possibility, following upon our previous findings concerning the, suggests a hypothesis of fundamental importance: the definite article in front of a noun is always and infallibly the sign of a restrictive adjunct, present or recover¬ able, attached to the noun. The proof of this hypothesis will require a somewhat technical discussion of restrictive adjuncts. But the, according to Russell, is ‘ a word of very great importance’, worth investigating even in prison or dead from the waist down.9

8 My first task, then, is to give a precise equivalent for the intuitive notion of a restrictive adjunct. I claim that all such adjuncts can be reduced to what the gram¬ marians call the restrictive relative clause. With respect to many ofthe examples used thus far the reconstruction of the relative clause is a simple matter indeed. All we have to know is that the relative pronoun — which, who, that, and so on — can be omitted between two noun phrases, and that the relative pronoun plus the copula can be omitted between a noun phrase and a string consisting of a preposition and a noun. Thus we can complete the full relative clauses in our familiar examples:

I see the water (which is) in the glass

The love (which) she felt for him was great

The man (whom) I saw wore a hat

The house (which) you sold yesterday has burned down

and so forth. If the conditions just given are not satisfied, wh.. .or wh.. .is cannot be omitted:

The man who came in is my brother.

The house which is burning is yours.

The reduction of prenominal adjectives to relative clauses is a less simple matter. In most cases, however, the following transformation is sufficient to achieve this:

(7) AN - N wh... is A10

as in

bald man - man who is bald

dirty water - water that is dirty

and so on. Later on we shall be able to show the correctness of (7).

In order to arrive at a precise notion of a restrictive relative clause, I have to say a few words about the other class of relative clauses, which are called appositive relative clauses. Some examples:

(8) You, who are rich, can afford two cars.

(9) Mary, whom you met, is my sister.

(10) Vipers, which are poisonous, should be avoided.

Our intuition tells us that the clauses here have no restrictive effect on the noun to which they are attached. You and Mary, as we recall, cannot be further restricted, and the range of vipers is not restricted either, since all vipers are poisonous. Indeed, (8)-(10) easily split into the following conjunctions:

(11) You are rich. You can afford two cars.

(12) You met Mary. Mary is my sister.

(13) Vipers are poisonous. Vipers should be avoided.

Thus we see that the appositive clause is nothing but a device for joining two sentences that share a noun phrase. One occurrence of the shared noun phrase gets replaced by the appropriate wh.. . and the resulting phrase (after some rearrangement of the word order when necessary) gets inserted into the other sentence following the occurrence of the shared noun phrase there. It is important to realize that this move does not alter the structure of the shared noun phrase in either of the ingredient sentences: the wh.. .replaces that noun phrase ‘as is’ in the enclosed sentence, and the clause gets attached to that noun phrase ‘ as is’ in the enclosing sentenced.11 It is not surprising, therefore, that the whole move leaves the truth-value of the ingredient sentences intact: (8)-(10) are true, if and only if the conjunctions in (11)-(13) are true.

This is not so with restrictive clauses. Compare (10) with

(14) Snakes which are poisonous should be avoided.

If we try to split (14) into two ingredients we get

(15) Snakes are poisonous. Snakes should be avoided.

Clearly, the conjunction in (15) is false, but (14) is true. And the reason for this fact is equally obvious. The clause which are poisonous is an integral part of the subject of (14); the predicate should he avoided is not ascribed to snakes but to snakes which are poisonous, that is, by virtue of (7), to poisonous snakes. It appears, therefore, that while the insertion of an appositive clause merely joins two complete sentences, the insertion of a restrictive clause alters the very structure of the enclosing sentence by completing one of its noun phrases. Consequently a mere conjunction of the ingredient sentences is bound to fall short of the information content embodied in the sentence containing the restrictive clause.

There are a few more or less reliable morphological clues that may help us in distinguishing these two kinds. First, appositive clauses, but not restrictive ones, are usually separated by a pause, or in writing by a comma, from the enclosing sentence. Second, which or who may be replaced by that in restrictive clauses, but hardly in appositive ones:

Snakes that are poisonous should be avoided

versus

Vipers, which are poisonous, should be avoided.

Finally, the omission of wh.. .or wh.. .is mentioned above works only in restrictive clauses:

The man you met is here

versus

*Mary, you met, is here.

9 I claim that the insertion of a restrictive clause after a noun is a necessary condition of its acquiring the definite article. Therefore the definite article does not belong either to the enclosing or to the enclosed sentence prior to the formation of the clause. Consider the sentence

(16) I know the man who killed Kennedy.

If we take the man to be the shared noun phrase, we get the ingredients

I know the man. The man killed Kennedy.

Here the man suggests some other identifying device, different from the one in (16), namely who killed Kennedy. In the case of a proper name this line of analysis leads to outright ungrammaticality. Consider, for example,

The Providence you know is no more.

Taking the Providence as the shared noun phrase we get the unacceptable

*You know the Providence. *The Providence is no more.

Thus we have to conclude that the ingredient sentences do not contain the definite article; it first enters the construction after the fusion of the two ingredients. Accordingly (16) is to be resolved into the following two sentences:

I know a man. A man killed Kennedy.

The shared noun phrase is a man. By replacing its second occurrence with who we obtain the clause who killed Kennedy. This gets inserted into the first sentence yielding

I know a man who killed Kennedy.

Since the verb kill suggests a unique agent, the definite article replaces the indefinite one, and we get (16). If the relevant verb has no connotation of uniqueness, no such replacement need take place; for instance,

I know a man who fought in Korea.

Of course we can say, in the plural,

(17) I know the men who fought in Korea.

In this case I imply that, in some sense or other,

I know all those men. If I just say I know men who fought in Korea

no completeness is implied; it is enough if I know some such men.

It transpires, then, that the definite article marks the speaker’s intention to exhaust the range determined by the restrictive clause. If that range is already restricted to one, the speaker’s hand is forced: the becomes obligatory; a sentence like

God spoke to a man who begot Isaac

is odd for this reason. In this case the semantics of beget already decides the issue. In other cases the option remains:

I see a tree in our garden

is as good as

I see the tree in our garden.

This latter remark, however, would be misplaced if, in fact, more than one tree is in our garden: the speaker promises uniqueness, which, in the given situation, the clause cannot deliver.

The way of producing a singular term out of a common noun is as follows: attach a restrictive clause to the noun in the singular and prefix the definite article. It may happen that the clause is not restrictive enough; its domain, in a given speech situation, may include more than one individual. This trouble is similar to the one created by saying

Joe is hungry

when more than one person is called Joe in the house. In either case there are several possibilities: the speaker may lack some information, may be just careless, may be intentionally misleading, or some such thing. Yet Joe or the tree in our garden remain singular terms. The fact that a tool can be misused does not alter the function of the tool. Later on I shall return to infelicities of this kind.

10 But this is only half the story. I mentioned above that in many cases the addition of the definite article alone seems to suffice to create a singular term out of a common noun:

(18) I see a man. The man wears a hat.

Obviously, we added, the man I see wears a hat. What happened is that the clause whom I see got deleted after the man, in view of the redundancy in the full sequence

I see a man. The man I see wears a hat.

The in (18), then, is nothing but a reminder of a deleted but recoverable restrictive clause. It is, as it were, a connecting device, which makes the discourse continuous with respect to a given noun. Indeed, if the is omitted, the two sentences become discontinuous:

I see a man. A man wears a hat.

Hence an important conclusion: the in front of a noun not actually followed by a restrictive clause is the sign of a deleted clause to be formed from a previous sentence in the same discourse containing the same noun. This rule explains the continuity in a discourse like

I have a dog and a cat. The dog has a ball to play with. Often the cat plays with the ball too

and the felt discontinuity in a text like

I have a dog and a cat. A dog has the ball.

If our conclusions are correct, then a noun in the singular already equipped with the definite article cannot take another restrictive clause, since such a noun phrase is a singular term as much as a proper name or a singular pronoun. Compare the two sequences:

(19) I see a man. The man wears a hat.

(20) I see a man. The man you know wears a hat.

(19) is continuous. The is the sign of the deleted clause {whom) I see. In (20) the possibility of this clause is precluded by the presence of the actual clause (whom) you know. The in (20) belongs to this clause and any further restrictive clauses are excluded. Consequently there is no reason to think that the man you know is the same as the man I see. Not so with appositive clauses. The sequence

I see a man. The man, whom you know, wears a hat

is perfectly continuous. The man, in the second sentence, has the deleted restrictive clause (whom) I see, plus the appositive clause whom you know. Now consider the following pair:

(21) I see a rose. The rose is lovely.

(22) I see a rose. The red rose is lovely.

(21) is continuous, (22) is not. This fact can be explained by assuming (7), that is, by deriving the prenominal adjective from a restrictive clause, which clause then precludes the acquisition of additional restrictive clauses. The assumption of (7), as we recall, also explains the difficulties encountered in trying to attach prenominal adjectives to proper names and personal pronouns.

11 The story, alas, is still not complete. Think of the ambiguity in a sentence like

(23) The man she loves must be generous.

This either means that there is a man whom she loves and who must be generous, or that any man she loves must be generous. Examples of this kind can be multiplied. In some of these the generic interpretation is the obvious one. For instance,

Happy is the man whose heart is pure.

It would be odd to continue:

I met him yesterday.

The natural sequel is rather:

I met one yesterday.12

In other cases the individual interpretation prevails:

The man she loved committed suicide.

Yet, with some imagination, even such a sentence can be taken in the generic sense.

How do we decide which interpretation is right in a given case? In order to arrive at an answer, imagine three discourses beginning as follows:

(24) Mary is a demanding girl. The man she loves must be generous.

(25) Mary loves a man. The man she loves must be generous.

(26) Mary loves a man. The man must be generous.

In (26) there is no ambiguity: the man is a singular term; in (25) it is likely to be a singular term; in (24) it is likely to be a general one. Why is this so? In (26) the deleted clause must be derived from the previous sentence, since, as we recall, the point of deletion is to remove redundancy. In {25) the clause is most likely a derivative of the previous sentence. If so, the man is a singular term. It remains possible, however, to imagine a break in the discourse between the two sentences: after stating a specific fact about her the speaker begins to talk about Mary in general terms. In (24) the reverse holds: the clause cannot be derived from a previous sentence, since there is no such sentence containing the noun, man. Consequently the man will be generic, unless a statement to the effect that Mary, in fact, loves a man is presupposed. Thus the moral of these examples emerges: a phrase of the type the N is a singular term if its occurrence is preceded by an actual or presupposed sentence of a certain kind in which N occurs, in the same discourse (the qualification, ‘ of a certain kind ’, will be explained soon). Accordingly, to take an occurrence of a the N-phrase to be a singular term is to assume the existence of such a sentence.

12 Since the always indicates a restrictive clause and since the only reason for deleting such a clause thus far mentioned is redundancy, that is, the presence of the sentence from which the clause is generated, one might conclude that no the N-phrase without a clause can occur if no such sentence can be found in the previous portion of the discourse. Yet this is not so. Some clause-less the N-phrases can occur at the very outset of a discourse. These counterexamples fall into three categories.

The first class comprises utterances of the following type:

The castle is burning.

The president is ill.

In these cases the clauses (in our town, of our country) are omitted simply because they are superfluous in the given situation. Such the N-phrases, in fact, approximate the status of proper names: they tend to identify by themselves. It is not surprising, therefore, that they are often spelled with a capital letter: the President, the Castle.

To a small circle of speakers even more common nouns can acquire this status:

Did you feed the dog?

The second category amounts to a literary device. One can begin a novel as follows:

The boy left the house.

Such a beginning suggests familiarity: the reader is invited to put himself into the picture: he is ‘there’, he sees the boy, he knows the house.

13 The third kind is entirely different. It involves a generic the without an actual clause. Examples abound:

(27) The mouse is a rodent

(28) The tiger lives in the jungle

(29) The Incas did not use the wheel

and so forth. It is obvious that no clause restricting mouse, tiger, or wheel is to be resurrected here: the ranges of these nouns remain unrestricted. Shall we, then, abandon our claim that the definite article always presupposes a restrictive clause? We need not and must not. In order to see this, consider the saying:

None but the brave deserves the fair.

The obvious paraphrase is

None but the [man who is] brave deserves the [woman who is] fair.

This suggests the following deletion pattern:

the N wh... is A -> the A

Then it is easy to see that sentences like

This book is written for the mathematician

Only the expert can give an answer

contain products of a similar pattern, to wit:

(30) the Nj wh. . .is an Nj → the Nj

Thus the mathematician and the expert come from the [person who is a] mathematician and the [person who is an] expert. And similarly, for (27)-(29) the sources are:

the [animal that is a] mouse (tiger)

the [instrument that is a] wheel.

We have seen above that a redundant clause can be omitted. In (30) a redundant noun, Ni, is omitted and the is transferred to Nj. Ni is redundant because it is nothing but Nj’s genus, and as such easily recoverable. This suggests that nouns that are themselves too generic to fall under a superior genus are not subject to (30). This is indeed so. While

Tigers live in the jungle

The Incas did not use wheels

do have (28) and (29) as paraphrases, sentences like

Objects are in space

Monkeys do not use instruments

are not paraphraseable into

The object is in space.

Monkeys do not use the instrument.13

In these sentences the the N-phrases have to be singular terms, consequently we are looking for the sentences from which the identifying clauses belonging to the object and the instrument are to be derived: what object (instrument) are we talking about?

This last point may serve as an indirect proof of (30). A more direct proof is forthcoming from the following example:

There are two kinds of large cat living in Paraguay, the jaguar and the puma. Obviously, the jaguar and the puma is derived from

the [(kind of) large cat that is a] jaguar and the [(kind of) large cat that is a] puma.

In this case, unlike some of the previous examples, neither a jaguar and a puma nor jaguars and pumas will do to replace the generic the jaguar and the puma. Thus the generic the is not a mere variant of other generic forms. It has an origin of its own. Another illustration:

Euclid described the parabola.

The parabola here is inadequately paraphrased by a parabola, parabolas or all parabolas. The given solution works again :

Euclid described the [(kind of) curve that is a] parabola.

Incidentally, although we might say

Euclid described curves

we cannot express this by saying

Euclid described the curve.

Curve is too generic.14

14 The possibility of transferring the from an earlier noun, exemplified in (30), indicates a solution for noun phrases containing a proper name with the definite article. The Hudson, the early Mozart, the Providence you know are most likely derived from

the [river called] Hudson

the early [period/works of] Mozart

the [aspect/appearance of] Providence you know.

Indeed, it can be shown that the clause you know, for instance, does not belong to Providence directly. For if it did, the following sequence would be acceptable:

You know Providence.* The Providence is no more

on the analogy of, say,

You had a house. The house is no more.

In this case the first sentence yields the clause which you had, which clause justifies the before house in the second sentence. In the previous example, however, the first sentence refuses to yield the clause which you know, precisely because Providence is a proper name. Thus Providence in the second sentence has no clause to justify the. Consequently the Providence you know does not come directly from

You know Providence.

15 Owing to the inductive nature of our investigations up to this point, our conclusions concerning the formation of singular terms out of common nouns had to be presented in a provisional manner leaving room, as it were, for the variety of facts still to be accounted for. Now, in retrospect, we are able to give a more coherent picture, at least in its main lines, for many details of this very complex affair must be left to further studies. The basic rules seem to be the following:

(a) The definite article is a function of a restrictive clause attached to the noun.

(b) This article indicates that the scope of the so restricted noun is to be taken exhaustively, extending to any and all objects falling under it.

(c) If the restriction is to one individual the definite article is obligatory and marks a singular term. Otherwise the term is general and the definite article remains optional.

(d) The clause is restrictive to one individual if and only if it is derived from a sentence either actually occurring in the previous part of the same discourse, or presupposed by the same discourse, and in which sentence A has an identifying occurrence. This last notion remains to be explained.

(e) Redundant clauses can be omitted.

(f) A clause is redundant if it is derived from a sentence actually occurring in the previous part of the discourse, or if the information content of a sentence in which A has an identifying occurrence is generally known to the participants of the discourse.

(g) Redundant genus nouns can be omitted according to (30).

16 These rules give us the following recognition-procedure with respect to any the N-phrase, where N is a common noun.

(i) If the phrase is followed by a clause look for the mother sentence of the clause.

(ii) If it is found, and if it identifies N, the phrase is a singular term. If it fails to identify, the phrase is a general term.

(iii) If no mother sentence can be found, ask whether the circumstances of the discourse warrant the assumption of an identifying sentence corresponding to the clause.

(iv) If the answer is in the affirmative, we have a singular term, otherwise a general one.

(v) If the phrase is not followed by a clause, look for a previous sentence in which N occurs without the definite article.

(vi) If there is such an occurrence the deleted clause after the phrase is to be recovered from that sentence.

(vii) If that occurrence is identifying we have a singular term, otherwise a general one.

(viii) If there is no such occurrence, ask whether the circumstances of the discourse warrant the assumption of a sentence that would identify N to the participants of the discourse.

(ix) If the answer is in the affirmative we have a singular term and the clause is to be recovered from that sentence.

(x) If the answer is in the negative the N is a general term with a missing genus to be recovered following (30).

In order to have an example illustrating the various possibilities for a singular term of the the N type, consider the following. My friend returns from a hunt and begins:

Imagine, I shot a bear and an elk. The bear I shot nearly got away, but the elk dropped dead on the spot. Incidentally, the gun worked beautifully, but the map you gave me was all wrong.

The bear I shot is a singular term by (ii). The elk is singular by (vii) with the clause I shot according to (vi). The gun is singular by (ix) with a clause something like I had with me; the map you gave me is singular by (iv).

The appeal to the circumstances of the discourse found in (iii) and (viii) is admittedly a cover for an almost inexhaustible variety of relevant considerations. Some of these are linguistic, others pragmatic. Tensed verbs suggest singular terms, modal contexts general ones. But think of the man Mary loves, who must be generous, and of the dinosaur, which roamed over Jurassic plains. In practice it may be impossible to arrive at a verdict in many situations. You may have only one cat, yet your wife’s remark

The cat is a clever beast

may remain ambiguous. What is important to us is rather the universal presupposition of all singular terms of the the N-type; the actual or implied existence of an identifying sentence. This notion still remains to be explained.

17 Once more I shall proceed in an inductive manner. First I shall enumerate the main types of identifying sentences and then try to find some common characteristics.

First of all, a sentence identifies N if it connects N with a definite noun phrase in a noncopulative and nonmodal fashion. The class of definite noun phrases comprises all singular terms and their plural equivalents like we, you, they, these hoys, my daughters, the dogs, and so forth. Consequently the following sentences are identifying ones:

(31) I see a house. The house. . .

(32) They dug a hole. The hole. . .

(33) The dogs found a bone. The bone. . .

The order of the noun phrases does not matter:

(34) A snake bit me. The snake. . .

PN adjuncts also connect both ways:

(35) They dug a hole with a stick. The stick. . .

(36) A boy had dinner with me. The boy. . .

and so forth.

It follows that definite nouns of the the N-type can form a chain of identification.

For instance:

I see a man. The man wears a hat. The hat has a feather on it. The feather is green.

But, of course, all chains must begin somewhere. This means that at the beginning of most discourses containing definite nouns, there must occur a ‘basic’ definite noun: a personal pronoun, a proper name, or a noun phrase beginning with a demonstrative or possessive pronoun. By these terms, as it were, the whole discourse is anchored in the world of individuals.

Copulative verbs like be and become do not connect. The following sequences remain discontinuous:

(37) He is a teacher. The teacher is lazy.

(38) Joe became a salesman. The salesman is well paid.

We know, of course, that these two verbs are peculiar in other respects too. Their verb object does not take the accusative and the sentences formed with them reject the passive transformation. What is more relevant for us, however, is the fact that these same verbs resist the formation of a relative clause:

*the teacher who he is

*the salesman he became.

This feature, of course, provides an unexpected confirmation for our theory about the definite article: (37) and (38) are discontinuous because the starting sentences cannot provide the clause for the subsequent the N-phrase.

Verbs accompanied by modal auxiliaries may or may not connect:

(39) Joe can lift a bear

(40) He could have married a rich girl

(41) You must buy a house

(42) I should have seen a play

remain ambiguous between generality and individuality concerning the second noun phrase.

In some cases nouns are identified by the mere presence of a verb in the past tense:

A man caught a shark in a lake. The shark was a fully developed specimen.

18 Finally, there is the least specific way of introducing a singular term:

Once upon a time there was a king who had seven daughters. The king.. .

This pattern of ‘ existential extraction ’ has great importance for us. It appears that it can be used as a criterion of identifying occurrence: a sentence is identifying with respect to an N if and only if the transform

There is an N wh..

is acceptable as a paraphrase. Thus the identifying sentences in (31)-(36) yield:

There is a house I see.

There is a hole they dug.

There is a bone the dogs found.

There is a snake that bit me.

There is a stick with which they dug a hole.

There is a boy who had dinner with me.

Nonidentifying sentences, like

A cat is an animal

A tiger eats meat

or the ones like (37)-(38), reject this form:

*There is an animal that is a cat.

*There is meat a tiger eats.

*There is a teacher he is.

*There is a salesman Joe became.

As for the modal sentences (39)-(42), it is obvious that the possibility of existential extraction is the sign of their being taken in the identifying sense:

There is a bear Joe can lift

There is a rich girl you could have married

and so on. We may conclude, then, that given any the N wh … …- phrase, it is a singular term if and only if the sentence There is an N wh … … is entailed by the discourse.

19 This conclusion should fill the hearts of all analytic philosophers with the glow of familiarity. Hence it may be worth while to review our conclusions from the point of view of recent controversies on the topic.

First of all we have found that the question whether or not a given the N-phrase is a singular term cannot be decided by considering only the sentence in which it occurs. Strawson’s suggestion that it is the use of the sentence, or the expression, that is relevant is certainly true, but it falls short of telling us what it means to use a sentence to make a statement, or to use a certain phrase to refer to something. Our results indicate a way of being more explicit and precise. At least with respect to the N-phrases, their being uniquely referring expressions, that is, singular terms, is conditioned by their occurrence in a discourse of a certain type. Such a discourse has to contain a previous sentence which identifies N, and, as we remember, such a sentence is always paraphraseable by the existential extraction, There is an N wh.... . . .Therefore, although Russell’s claim, according to which sentences containing the N-type singular terms entail an assertion of existence, is too strong, Strawson’s claim, that no such assertion is entailed by the referential occurrence of such a phrase is too weak. True, it is not the sentence containing the referential the N that entails the existential assertion, but another sentence, the occurrence of which, however, is a conditio sine qua non of a referential the N.

But, you object, the identifying sentence need not actually occur. In many cases it is merely assumed or presupposed. My answer is that this is philosophically irrelevant. The omission of the identifying sentence is a device of economy: we do not bother to state the obvious. What matters is the essential structure of the discourse. In giving a mathematical proof we often omit steps that are obvious to the audience, yet those steps remain part of the proof. The omission of the identifying sentence, like the omission of certain steps in a given proof, depends upon what the speaker deems to be obvious to the audience in question. And this has no philosophical significance.

Our conclusion is in accordance with common sense. If a child tells me

(43) The bear I shot yesterday was huge

I will answer

(44) But you did not shoot any bear.

(44) does not contradict

(43). It contradicts, however, the sentence

(45) I shot a bear yesterday

which the child presupposed, but wisely omitted, in trying to get me to take the bear . . .as a referring expression. Is, then, (43) true or false? In itself it is neither, since the the N-phrase in it can achieve reference only if the preceding identifying sentence, (45), is true. Since this is not the case, the bear.. . fails to refer to anything in spite of the fact that it satisfies the conditions for a singular term.

Of course the logician, who abhors truth-gaps as nature does the void will be justified in trying to unmask the impotence of such singular terms by insisting upon the inclusion of a version of the relevant identifying sentence (There is an N wh.. . . . .) into the analysis of sentences containing singular the N terms. In view of our results, this move is far less artificial than some authors have claimed.

20 The triumph of the partisans of the philosophical theory of descriptions will, however, be somewhat damped when we point out that sentences of the type

There is an N wh.

do not necessarily assert ‘real’ existence, let alone spatio-temporal existence. Take the following discourse:

I dreamt about a ship. The ship...

The identifying sentence easily yields the transform

There is a ship I dreamt about.

This may be true, yet it does not mean that there is such a ship in reality. If somebody suggests that that ship has a dream existence, or that the house I just imagined has an imaginary existence, or that the king with the seven daughters has a fairytale existence, I cannot but agree. I only add that it would be desirable to be able to characterize the various types of discourse appropriate to these kinds of ‘ existence ’. Particularly, of course, we are interested in discourses pertaining to ‘ real ’ existence. I give a hint. I remarked above that at the beginning of almost every discourse containing singular terms there must be a ‘ basic ’ singular term (or its plural equivalent). Now if we find such a basic term denoting a real entity, like I, Lyndon B. Johnson, or Uganda, then we should trace the connection of other singular terms to these. As long as the links are formed by ‘ reality-preserving ’ verbs like push, kick, and eat, we remain in spatio-temporal reality. Verbs like dream, imagine, need, want, look for, and plan should caution us: the link may be broken, although it need not be. Reality may enter by another path. If I only say

I dreamt about a house. The house. . .

one has no reason to think that the house I dreamt about is to be found in the world. If, however, I report

I dreamt about the house in which I was born. The house. ..

the house I talk about is a real house, but not by virtue of dream but by virtue of being born in. It is this latter and not the former verb that preserves reality. Of course, if the ‘ basic ’ singular term is something like Zeus, or the king who lived once upon a time, the situation is clear. The development of this hint would require much fascinating detail.

For the time being, we have to be satisfied with the conclusion that the discourse in which a referential the N-phrase occurs entails a There is an N. . .assertion. But we should add the caveat: there are things that do not really exist.15

1 This paper is reprinted from Vendler, Linguistics in Philosophy, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1967, pp. 33-69.

2 ‘ Quine uses the expression “ term” in application to linguistic items only, whereas I apply it to non-linguistic items’ (P. F. Strawson, Individuals, p. 154 n).

3 See, for example, B. Russell, ‘Descriptions’, ch. 16 in Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy, pp. 167-80; W. V. Quine, Methods of Logic, pp. 220 ff.

4 On the notion of co-occurrence see Z. S. Harris, ‘Co-occurrence and Transformation in Linguistic Structure’, Language, XXXIII (1957), 283-340.

5 The technical notion, ‘ the phrase x is an adjunct of the phrase y’ roughly corresponds to the intuitive notion of one phrase ‘modifying’ another. See Z. S. Harris, String Analysis of Sentence Structure, pp. 9 ff.

6 Mass nouns can take the indefinite article only in explicit or implicit combination with ‘ measure ’ nouns: a pound of meat, a cup of coffee; phrases like a coffee, are products of an obvious deletion: a [cup of] coffee.

7 We, you, and they are used to refer to unique groups of individuals. Here, as in the sequel, I restrict myself to the discussion of definite noun phrases in the singular. It is clear, however, that our findings will apply mutatis mutandis to definite noun phrases in the plural as well: those houses, our dogs, the children you see, and so forth. From a logical point of view these phrases show a greater affinity to singular than to general terms. See P. F. Strawson, ‘ On Referring’, Mind, lix (1950), 343-4.

8 P. F. Strawson, Individuals, p. 147.

9 Russell, ‘Descriptions’, p. 167.

10 Wh.. . stands for the appropriate relative pronoun.

11 The shared noun phrase need not have an identical form in the original sentences. From I bought a house, which has two stories we recover I bought a house. The house (I bought) has two stories. These two sentences are continuous with respect to the noun house. This notion of continuity will be explained later.

12 It is interesting to realize that a personal pronoun, like he, also can occur in a generic sense - e.g., He who asks shall be given.

13 The existence or nonexistence of a higher genus may be a function of the discourse. In philosophical writing, for instance, one might find a generic sentence like The idea is more perfect than the object, which presupposes a common genus for ideas and objects.

14 As man is an exceptional animal, man is an exceptional noun. It has a generic sense in the singular without any article: Man, but not the ape, uses instruments.

15 The author wishes to express his indebtedness to the work of Dr Beverly L. Robbins later published in The Definite Article in English Transformations. The Hague, Mouton, 1968.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)