النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Suppressors May Compete with Wild-Type Reading of the Code

المؤلف:

JOCELYN E. KREBS, ELLIOTT S. GOLDSTEIN and STEPHEN T. KILPATRICK

المصدر:

LEWIN’S GENES XII

الجزء والصفحة:

1-6-2021

3320

Suppressors May Compete with Wild-Type Reading of the Code

KEY CONCEPTS

- Suppressor tRNAs compete with wild-type tRNAs that have the same anticodon to read the corresponding codon(s).

- Efficient suppression is deleterious because it results in readthrough past natural termination codons.

- The UGA codon is “leaky” and is misread by Trp-tRNA at 1% to 3% frequency.

An interesting difference exists between the usual recognition of a codon by its proper aminoacyl-tRNA and the situation in which mutation allows a suppressor tRNA to recognize a new codon. In the wild-type cell, only one meaning can be attributed to a particular codon, which represents either a particular amino acid or a signal for termination. However, in a cell carrying a suppressor mutation the mutant codon may either be recognized by the suppressor tRNA or be read with its usual meaning.

A nonsense suppressor tRNA must compete with the release factors that recognize the termination codon(s). A missense suppressor tRNA must compete with the tRNAs that respond properly to its new codon. In each case, the extent of competition influences the efficiency of suppression, so the effectiveness of a particular suppressor depends not only on the affinity between its anticodon and the target codon but also on its concentration in the cell and on the parameters governing the competing termination or insertion reactions.

The efficiency with which any particular codon is read is influenced by its location. Thus, the extent of nonsense suppression by a particular tRNA can vary quite widely, depending on the context of the codon. The effect that neighboring bases in mRNA have on codon–anticodon recognition is poorly understood, but the context can change the frequency with which a codon is recognized by a particular tRNA by more than an order of magnitude.

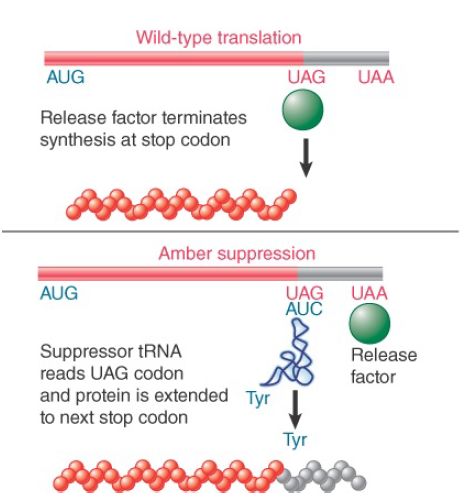

A nonsense suppressor is isolated by its ability to respond to a mutant nonsense codon. However, the same triplet sequence constitutes one of the normal termination signals of the cell. The mutant tRNA that suppresses the nonsense mutation must, in principle, be able to suppress natural termination at the end of any gene that uses this codon. FIGURE 1 shows that this readthrough results in the synthesis of a longer polypeptide, with additional C-terminal sequence. The extended polypeptide will end at the next termination triplet sequence found in the reading frame. Any extensive suppression of termination is likely to be deleterious to the cell by producing extended polypeptides whose functions are thereby altered.

FIGURE 1. Nonsense suppressors also read through natural termination codons, synthesizing polypeptides that are longer than the wild type.

Amber suppressors tend to be relatively efficient, usually in the range of 10% to 50%, depending on the system. This efficiency is possible because amber codons are used relatively infrequently to terminate translation in E. coli. In contrast, ochre suppressors are difficult to isolate. They are always much less efficient, usually with activities below 10%. All ochre suppressors grow rather poorly, which indicates that suppression of both UAA and UAG is damaging to E. coli, probably because the UAA ochre codon is used most frequently as a natural termination signal. Finally, UGA is the least efficient of the termination codons in its natural function; it is misread by tRNATrp as frequently as 1% to 3% in wild-type cells. However, in spite of this deficiency, UGA is used more commonly than the amber triplet UAG to terminate bacterial translation.

A missense suppressor tRNA that compensates for a mutated codon at one position may have the effect of introducing an unwanted mutation in another gene. A suppressor corrects a mutation by substituting one amino acid for another at the mutant site. However, in other locations, the same substitution will replace the wild-type amino acid with a new amino acid. The change may inhibit normal polypeptide function. This poses a dilemma for the cell: It must suppress what is a mutant codon at one location but not change too extensively its normal meaning at other locations. The absence of any strong missense suppressors is most likely explained by the damaging effects that would be caused by a general and efficient substitution of amino acids.

A mutation that creates a suppressor tRNA can have two consequences. First, it allows the tRNA to recognize a new codon. Second, it sometimes prevents the tRNA from recognizing the codons to which it previously responded. It is significant that all the high-efficiency amber suppressors are derived by mutation of one copy of a redundant tRNA set. In these cases, the cell has several tRNAs able to respond to the codon originally recognized by the wild-type tRNA. Thus, the mutation does not abolish recognition of the old codons, which continue to be served adequately by the tRNAs of the set. In the unusual situation in which there is only a single tRNA that responds to a particular codon, any mutation that prevents the response would be lethal.

Suppression is most often considered in the context of a mutation that changes the reading of a codon. However, in some situations a stop codon is read as an amino acid at a low frequency in wild-type cells. The first example discovered was the coat protein gene of the RNA phage Qβ. The formation of infective Qβ particles requires that the stop codon at the end of this gene be suppressed at a low frequency to generate a small proportion of coat proteins with a Cterminal extension. In effect, this stop codon is leaky. The reason is that tRNATrp recognizes the codon at a low frequency.

Readthrough past stop codons also occurs in eukaryotes, where it is employed most often by RNA viruses. This may involve the suppression of UAG/UAA by tRNATyr , tRNAGln , or tRNALeu or the suppression of UGA by tRNATrp or tRNAArg . The extent of partial suppression is dictated by the context surrounding the codon.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)