النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Introduction to Genes and Chromosomes

المؤلف:

JOCELYN E. KREBS, ELLIOTT S. GOLDSTEIN and STEPHEN T. KILPATRICK

المصدر:

LEWIN’S GENES XII

الجزء والصفحة:

23-2-2021

2637

Introduction to Genes and Chromosomes

The hereditary basis of every living organism is its genome, a long sequence of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) that provides the complete set of hereditary information carried by the organism as well as its individual cells. The genome includes chromosomal DNA as well as DNA in plasmids and (in eukaryotes) organellar DNA, as found in mitochondria and chloroplasts. We use the term

information because the genome does not itself perform an active role in the development of the organism. Rather, the products of expression of nucleotide sequences within the genome determine development. By a complex series of interactions, the DNA sequence directs production of all of the ribonucleic acids (RNAs) and proteins of the organism at the appropriate time and within the appropriate cells. Proteins serve a diverse series of roles in the development and functioning of an organism: they can form part of the structure of the organism; have the capacity to build the structure; perform the metabolic reactions necessary for life; and participate in regulation as transcription factors, receptors, key players in signal transduction pathways, and other molecules.

Physically, the genome can be divided into a number of different DNA molecules, or chromosomes. The ultimate definition of a genome is the sequence of the DNA of each chromosome.

Functionally, the genome is divided into genes. Each gene is a sequence of DNA that encodes a single type of RNA and, in many cases, ultimately a polypeptide. Each of the discrete chromosomes comprising the genome can contain a large number of genes.

Genomes for living organisms might contain as few as about 500 genes (for mycoplasma, a type of bacterium), about 20,000 for humans, or as many as about 50,000 to 60,000 for rice.

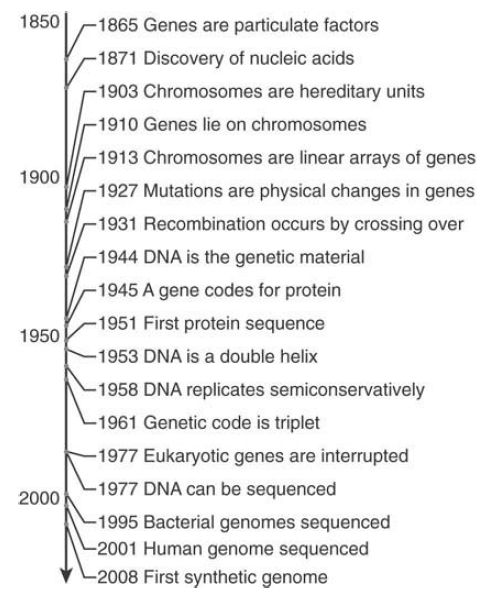

In this chapter, we explore the gene in terms of its basic molecular construction and basic function. FIGURE 1.1 summarizes the stages in the transition from the historical concept of the gene to the modern definition of the genome.

FIGURE 1.1 A brief history of genetics.

The first definition of the gene as a functional unit followed from the discovery that individual genes are responsible for the production of specific proteins. Later, the chemical differences between the DNA of the gene and its protein product led to the suggestion that a gene encodes a protein. This, in turn, led to the discovery of the complex apparatus by which the DNA sequence of a gene determines the amino acid sequence of a polypeptide.

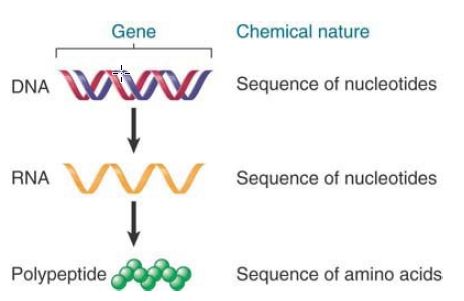

Understanding the process by which a gene is expressed allows us to make a more rigorous definition of its nature. FIGURE 1.2 shows the basic theme of this book. A gene is a sequence of DNA that directly produces a single strand of another nucleic acid, RNA, with a sequence that is (at least initially) identical to one of the two polynucleotide strands of DNA. In many cases, the RNA is in turn used to direct production of a polypeptide. In other cases, such as ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, the RNA transcribed from the gene is the functional end product. Thus, a gene is a sequence of DNA that encodes an RNA, and in proteincoding, or structural, genes, the RNA in turn encodes a polypeptide.

FIGURE 1.2 A gene encodes an RNA, which can encode a polypeptide.

The gene is the functional unit of heredity. Each gene is a sequence within the genome that functions by giving rise to a discrete product, which can be a polypeptide or an RNA. The basic pattern of inheritance of a gene was proposed by Mendel nearly 150 years ago. Summarized in his two major principles of segregation and independent assortment, the gene was recognized as a “particulate factor” that passes largely unchanged from parent to progeny. A gene can exist in alternative forms, called alleles.

In diploid organisms (having two sets of chromosomes), one of each chromosome pair is inherited from each parent. This is the same pattern of inheritance that is displayed by genes. One of the two copies of each gene is the paternal allele (inherited from the father); the other is the maternal allele (inherited from the mother).

The shared pattern of inheritance of genes and chromosomes led to the discovery that chromosomes in fact carry the genes. Each chromosome consists of a linear array of genes, and each gene resides at a particular location on the chromosome. The location is more formally called a genetic locus. The alleles of a gene are the different forms that are found at its locus. Although generally there are up to two alleles per locus in a diploid individual, a population might have many alleles of a single gene.

The key to understanding the organization of genes into chromosomes was the discovery of genetic linkage—the tendency for genes on the same chromosome to remain together in the

progeny instead of assorting independently as predicted by Mendel’s principle. After the unit of recombination (reassortment) was introduced as the measure of linkage, the construction of genetic maps became possible. The recombination frequency between loci is proportional to the physical distance between the loci.

The resolution of the recombination map of a multicellular eukaryote is restricted by the small number of progeny that can be obtained from each mating. Recombination occurs so infrequently between nearby points that it is rarely observed between different variable sites in the same gene. As a result, classic linkage maps of eukaryotes can place the genes in order but cannot resolve the locations of variable sites within a gene. By using a microbial system in which a very large number of progeny can be obtained from each genetic cross, researchers could demonstrate that recombination occurs within genes and that it follows the same rules as those for recombination between genes.

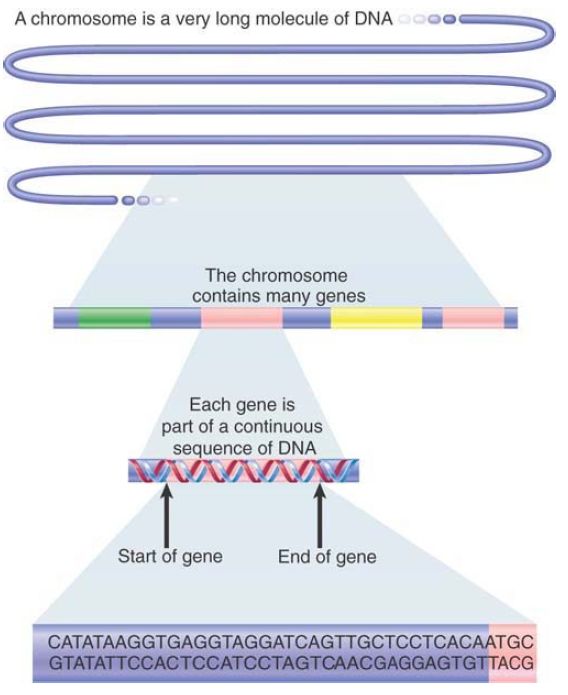

Variable nucleotide sites among alleles of a gene can be arranged into a linear order, showing that the gene itself has the same linear construction as the array of genes on a chromosome. In other words, the genetic map is linear within, as well as between, loci as an unbroken sequence of nucleotides. This conclusion leads naturally to the modern view summarized in FIGURE 1.3 that the genetic material of a chromosome consists of an uninterrupted length of DNA representing many genes. Having defined the gene as an uninterrupted length of DNA, it should be noted that in eukaryotes many genes are interrupted by sequences in the DNA that are then excised from the messenger RNA (mRNA) . Furthermore, there are regions of DNA that control the timing and pattern of expression of genes that can be located some distance from the gene itself.

FIGURE 1.3 Each chromosome consists of a single, long molecule of DNA within which are the sequences of individual genes.

From the demonstration that a gene consists of DNA, and that a chromosome consists of a long stretch of DNA representing many genes, we will move to the overall organization of the genome.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)