The source of spin-spin coupling

The 1H-NMR spectra that we have seen so far (of methyl acetate and para-xylene) are somewhat unusual in the sense that in both of these molecules, each set of protons generates a single NMR signal. In fact, the 1H-NMR spectra of most organic molecules contain proton signals that are 'split' into two or more sub-peaks. Rather than being a complication, however, this splitting behavior actually provides us with more information about our sample molecule.

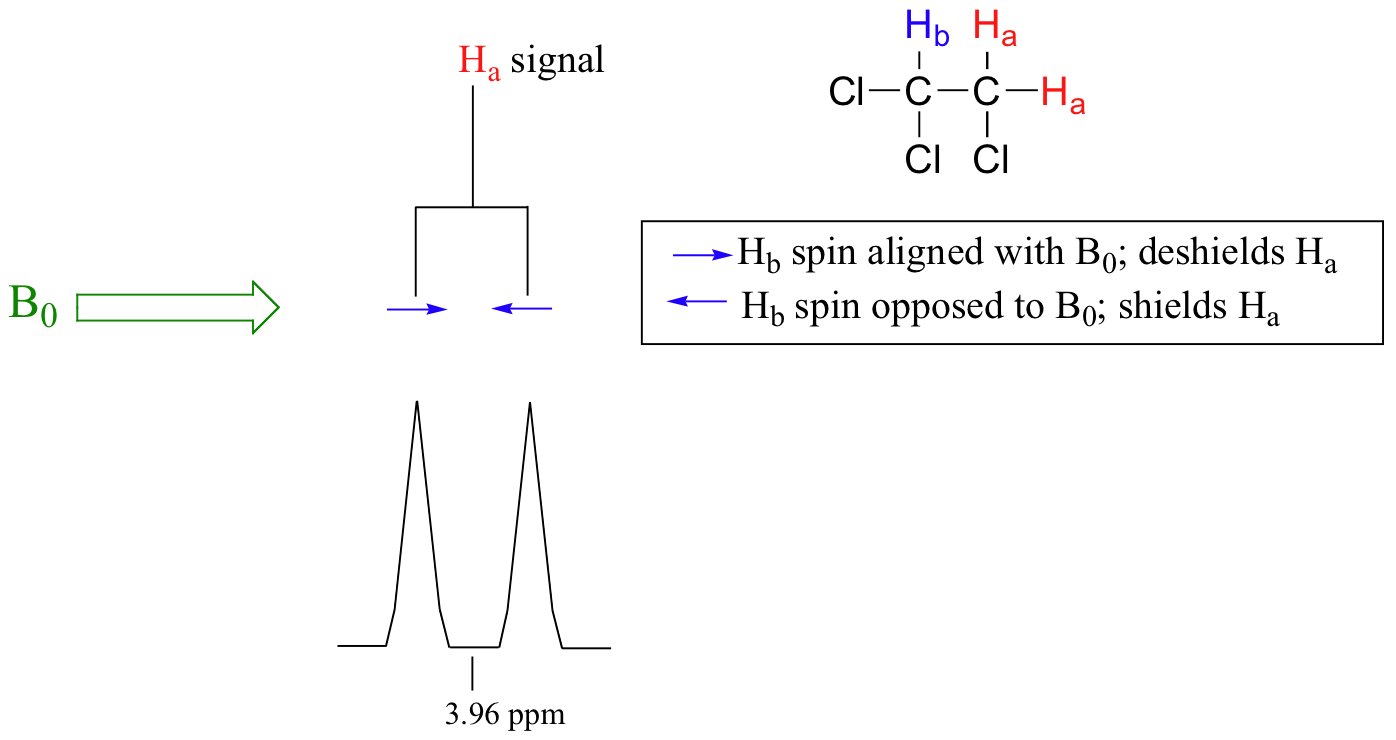

Consider the spectrum for 1,1,2-trichloroethane. In this and in many spectra to follow, we show enlargements of individual signals so that the signal splitting patterns are recognizable.

The signal at 3.96 ppm, corresponding to the two Ha protons, is split into two subpeaks of equal height (and area) – this is referred to as a doublet. The Hb signal at 5.76 ppm, on the other hand, is split into three sub-peaks, with the middle peak higher than the two outside peaks - if we were to integrate each subpeak, we would see that the area under the middle peak is twice that of each of the outside peaks. This is called a triplet.

The source of signal splitting is a phenomenon called spin-spin coupling, a term that describes the magnetic interactions between neighboring, non-equivalent NMR-active nuclei. In our 1,1,2 trichloromethane example, the Ha and Hb protons are spin-coupled to each other. Here's how it works, looking first at the Ha signal: in addition to being shielded by nearby valence electrons, each of the Ha protons is also influenced by the small magnetic field generated by Hb next door (remember, each spinning proton is like a tiny magnet). The magnetic moment of Hb will be aligned with B0 in (slightly more than) half of the molecules in the sample, while in the remaining half of the molecules it will be opposed to B0. The Beff ‘felt’ by Ha is a slightly weaker if Hb is aligned against B0, or slightly stronger if Hb is aligned with B0. In other words, in half of the molecules Ha is shielded by Hb (thus the NMR signal is shifted slightly upfield) and in the other half Ha is deshielded by Hb(and the NMR signal shifted slightly downfield). What would otherwise be a single Ha peak has been split into two sub-peaks (a doublet), one upfield and one downfield of the original signal. These ideas an be illustrated by a splitting diagram, as shown below.

Now, let's think about the Hbsignal. The magnetic environment experienced by Hb is influenced by the fields of both neighboring Ha protons, which we will call Ha1 and Ha2. There are four possibilities here, each of which is equally probable. First, the magnetic fields of both Ha1 and Ha2 could be aligned with B0, which would deshield Hb, shifting its NMR signal slightly downfield. Second, both the Ha1 and Ha2 magnetic fields could be aligned opposed to B0, which would shield Hb, shifting its resonance signal slightly upfield. Third and fourth, Ha1 could be with B0 and Ha2 opposed, or Ha1opposed to B0 and Ha2 with B0. In each of the last two cases, the shielding effect of one Ha proton would cancel the deshielding effect of the other, and the chemical shift of Hb would be unchanged.

So in the end, the signal for Hb is a triplet, with the middle peak twice as large as the two outer peaks because there are two ways that Ha1 and Ha2 can cancel each other out. Now, consider the spectrum for ethyl acetate:

We see an unsplit 'singlet' peak at 1.833 ppm that corresponds to the acetyl (Ha) hydrogens – this is similar to the signal for the acetate hydrogens in methyl acetate that we considered earlier. This signal is unsplit because there are no adjacent hydrogens on the molecule. The signal at 1.055 ppm for the Hc hydrogens is split into a triplet by the two Hb hydrogens next door. The explanation here is the same as the explanation for the triplet peak we saw previously for 1,1,2-trichloroethane.

The Hbhydrogens give rise to a quartet signal at 3.915 ppm – notice that the two middle peaks are taller then the two outside peaks. This splitting pattern results from the spin-coupling effect of the three Hc hydrogens next door, and can be explained by an analysis similar to that which we used to explain the doublet and triplet patterns.

By now, you probably have recognized the pattern which is usually referred to as the n + 1 rule: if a set of hydrogens has n neighboring, non-equivalent hydrogens, it will be split into n + 1 subpeaks. Thus the two Hb hydrogens in ethyl acetate split the Hc signal into a triplet, and the three Hc hydrogens split the Hb signal into a quartet. This is very useful information if we are trying to determine the structure of an unknown molecule: if we see a triplet signal, we know that the corresponding hydrogen or set of hydrogens has two `neighbors`. When we begin to determine structures of unknown compounds using 1H-NMR spectral data, it will become more apparent how this kind of information can be used.

Three important points need to be emphasized here. First, signal splitting only occurs between non-equivalent hydrogens – in other words, Ha1 in 1,1,2-trichloroethane is not split by Ha2, and vice-versa.

Second, splitting occurs primarily between hydrogens that are separated by three bonds. This is why the Ha hydrogens in ethyl acetate form a singlet– the nearest hydrogen neighbors are five bonds away, too far for coupling to occur.

Occasionally we will see four-bond and even 5-bond splitting, but in these cases the magnetic influence of one set of hydrogens on the other set is much more subtle than what we typically see in three-bond splitting. Finally, splitting is most noticeable with hydrogens bonded to carbon. Hydrogens that are bonded to heteroatoms (alcohol or amino hydrogens, for example) are coupled weakly - or not at all - to their neighbors. This has to do with the fact that these protons exchange rapidly with solvent or other sample molecules.

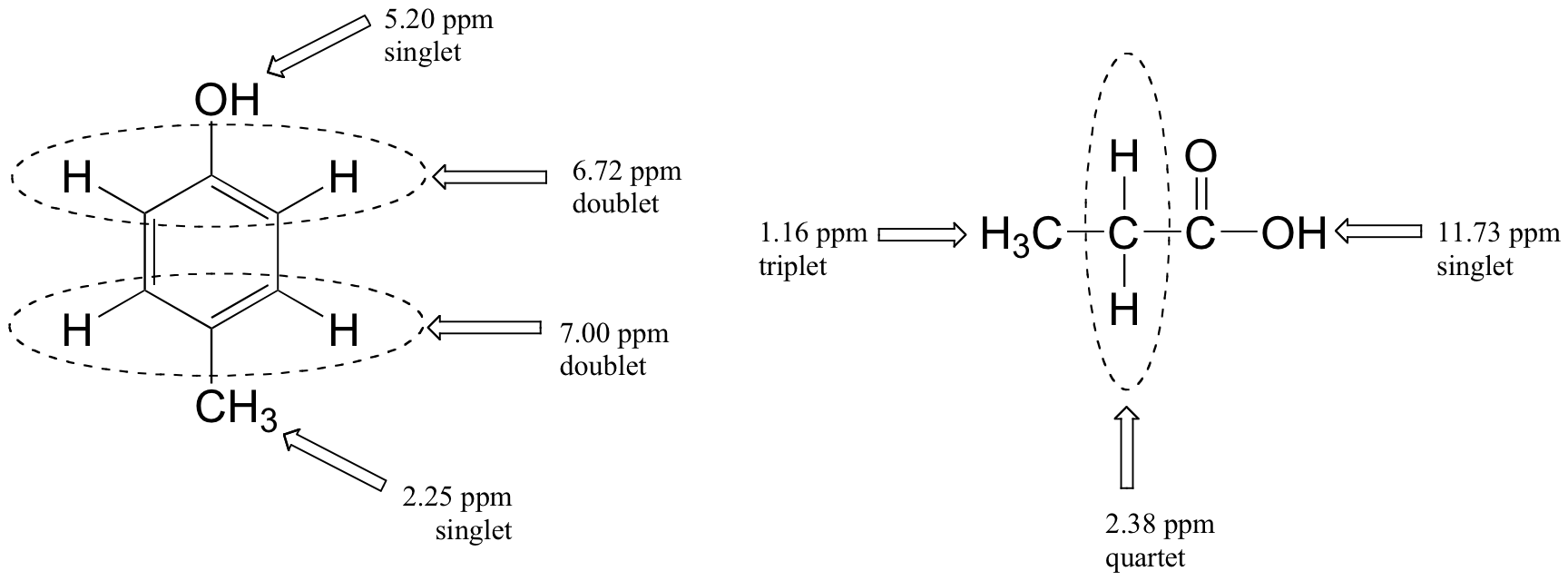

Below are a few more examples of chemical shift and splitting pattern information for some relatively simple organic molecules.