النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 14-11-2016

Date: 14-11-2016

Date: 21-11-2016

|

Introduction to Roots

Most roots have three functions: (1) anchoring the plant firmly to a substrate, (2) absorbing water and minerals, and (3) producing hormones. Firm anchoring provides stability and is therefore important for virtually all plants. Stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits then can be properly oriented to the sun, to pollinators, or to fruit distributors. Without proper root attachment, trees and shrubs could not remain upright, and epiphytes would be blown from their sites in the tree canopy. A highly branched rhizomatous or stoloniferous plant resist being blown over even without roots, but the horizontal stems are usually so flexible that roots are necessary to stabilize the aerial structure.

Although roots, like leaves, have an absorptive function, the two organs have totally different shapes. Sunlight always comes from above, but water and minerals are distributed on all sides of a root. Its cylindrical shape allows all sides to have the same absorptive capacity. Consider a leaf and a system of thin roots, both with equal volumes; the root system has a higher surface-to-volume ratio, ideal for absorption. The lower surface-to-volume ratio for leaves reduces the carbon dioxide absorption capacity but not the absorption of light and is actually beneficial for water conservation. Roots do not need to be adapted for light absorption, and they absorb water rather than needing to conserve it. Their cylindrical shape is also undoubtedly related to the growth of the roots through a semisolid, resistant medium. Even a light, porous soil can be most easily and thoroughly penetrated by narrow cylinders rather than thin sheets. Thus, although both leaves and roots have absorptive functions, it is selectively advantageous for them to have different shapes.

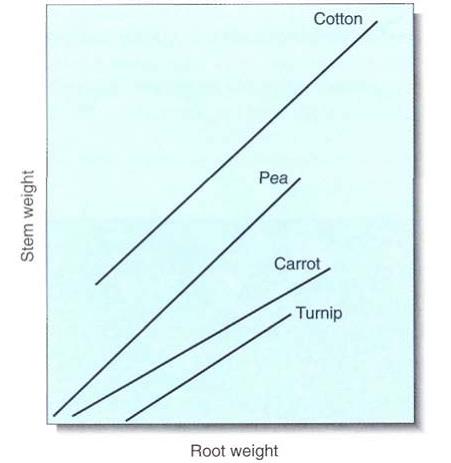

Roots are quite active in the production of several hormones; shoot growth and development depend on the hormones cytokinin and gibberellin imported from the roots. This reliance of the shoot on root-produced hormones may be a means of integrating the growth of the two systems. It is selectively advantageous for a plant to control the size of its shoot so that transpiration by its leaves does not exceed absorption by its roots. Nor should a plant waste carbohydrate by constructing a larger root system than its shoot needs; the extra carbohydrate could be used for leaves or reproduction (Fig. ).

In many cases, roots have functions in addition to or instead of anchoring, absorption, and hormone production. Fleshy taproots, such as those of carrots, beets, and radishes, are the plant's main site of carbohydrate storage during winter. As the roots of willows, sorrel, and other plants spread horizontally, they produce shoot buds that grow out and act as new plants. This method of vegetative reproduction is quite similar to that of stoloniferous and rhizomatous plants, except that roots rather than stems are involved. In the palms Crysophila and Mauritia, roots grow out of the trunk and then harden into sharp spines. Ivy and many other vines have modified roots that act as holdfasts, clinging to rock or brick. Finally, many parasitic flowering plants (mistletoe, dodder) attack other plants and draw water and nutrients out of them through modified roots.

Distinct sets of characteristics are adaptive for the different root functions. As roots specialize and become more efficient for particular tasks, they become poorly adapted for other tasks, so several types of roots may occur in one plant, resulting in division of labor. For example, in addition to the large storage root, carrots and beets also have fine absorptive roots, and ivy has both holdfasts and absorptive roots. The characteristic types of structure and metabolism of each should be analyzed in terms of the function of the particular root.

FIGURE :The ratio of root system to shoot system is critically important; for each species, as the root system becomes heavier, so does the shoot system by a characteristic amount. However, the relationship differs for each species: Obviously for a given amount of turnip root there is relatively little shoot, but there is much more shoot for the same amount of pea root, and even more for cotton.

|

|

|

|

لخفض ضغط الدم.. دراسة تحدد "تمارين مهمة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

طال انتظارها.. ميزة جديدة من "واتساب" تعزز الخصوصية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مشاتل الكفيل تزيّن مجمّع أبي الفضل العبّاس (عليه السلام) بالورد استعدادًا لحفل التخرج المركزي

|

|

|