Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-05-02

Date: 2025-03-08

Date: 2024-04-15

|

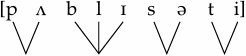

Although finding the peaks of sonority aids us greatly in identifying the number of syllables in a word, it does not tell us much about the syllabification, that is, where the syllable boundaries lie. For example, where do the intervocalic consonants belong in publicity? How do we assign /b/ and /l/ between the first and the second syllables? What about the /s/? Is it the coda of the second syllable or the onset of the third?

The principle on which we make the decision in these cases, which is known as the ‘maximal onset principle’, simply assigns any series of intervocalic consonants to the syllable on the right as long as it does not violate language-specific onset patterns. To demonstrate this, let us look at the word publicity again. This word, unambiguously, has four syllables and the nuclei are clearly identifiable vowels. First, we need to phonetically transcribe the word and identify the syllable nuclei.

The next step is to go to the end of the word and start connecting the nucleus of each syllable with the surrounding consonants. The last syllable has no coda, and the nucleus will be attached to the preceding /t/, because [ti] is an acceptable sequence in English. After this, we move to the nucleus of the preceding (third) syllable, which is an [ə]; the lack of any coda in this syllable and the acceptability of a [sə] sequence in English tell us that this will be the third syllable of the word. There are two consonants to the left of the nucleus of the second syllable /ɪ/. Connecting /ɪ/ to the immediately preceding /l/ is no problem, as [lɪ] is a perfectly normal sequence in English. The next consonant to the left, /b/, is also going to be connected with the second syllable, because the resulting [bl] is an acceptable onset in the language (e.g. blue [blu], block [blɔk]). Thus, the resulting syllabification of this word will be:

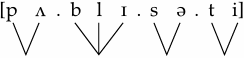

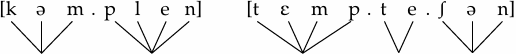

Sometimes, we see the same sequences of sounds syllabified differently in different words. We will illustrate this phenomenon in the following two words, complain and temptation. The syllabifications of these two words are given in the following:

Our focus will be the [mp] sequence the two words share. As the syllabifications above make clear, the same sequence behaves differently in the two words. While in temptation [tεmp.te.ʃən] the [mp] sequence is the double coda of the first syllable, in complain [kəm.plen] the two sounds fall into separate syllables; [m] belongs to the coda of the first syllable, and [p] is part of the double onset of the second syllable. The reason for this difference is what is allowed as a maximal onset in English. Since [pt] is not a possible onset, [p] has to stay in the first syllable of temptation. In complain, however, [p] is part of the onset of the second syllable because [pl] is a permissible onset in English.

Dividing the word complain as [kəmp.len] would not have resulted in any violation of English onsets or codas, because both [kəmp] and [len] are permissible in the language. However, doing this would have meant maximizing the coda. The observed syllabification [kəm.plen], on the other hand, follows the maximization of allowed onsets in English. Assigning intervocalic consonants as onsets of the following syllable rather than coda of the preceding syllable forms the basis of the maximal onset principle, and this is derived from the fact that onsets are more basic than codas in languages. All languages, without a single exception, have CV (open) syllables, whereas many languages lack VC (closed) syllables. To summarize what has been said so far, we can say that the principle that guides spoken syllabification assigns the maximum allowable number of consonants to the syllable on the right.

Before we leave this section, we should emphasize the importance of the language-specific nature of syllabification, as the same sequence of sounds may be divided differently in different languages. To illustrate this point, let us look at the following two cases, /bl/ and /sl/, and compare the situation in English with two other languages. In Turkish there are no onset clusters, although the sequence [bl] may be found across syllables. For example, the word abla “older sister” would invariably be divided as [ab.la]. This is very different from the [bl] sequence of English in [pΛ.blɪ.sə.ti]. For [sl], we can compare English with Spanish. Although Spanish has onset clusters, these are not allowed with /s/ as the first member. This does not mean that there are no [sl] sequences in the language. The word [isla] “island” shows that this is pos sible with the following syllabification: [is.la]. In English, however, since [sl] is a possible onset, the syllabification of a word such as asleep is [ə.slip]. These two examples demonstrate that the way a given sequence of sounds may behave is strictly dependent on language-specific patterns. Finally, if we can state the obvious from the examples above, we can predict that native speakers of Turkish will attempt the syllabification of publicity as [pΛb.lɪ.sə.ti], and native speakers of Spanish will reveal [əs.lip] for asleep in their attempts to acquire English as a foreign language.

|

|

|

|

هدر الطعام في رمضان.. أرقام وخسائر صادمة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

كالكوبرا الباصقة.. اكتشاف عقرب نادر يرش السم لمسافات بعيدة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية تنشر لافتات احتفائية بذكرى ولادة الإمام الحسن (عليه السلام)

|

|

|