Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-03-06

Date: 2024-06-08

Date: 2024-03-02

|

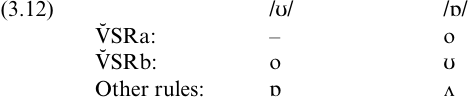

Alax-vowel VSR of the type proposed by McCawley (1986) will produce the derivations in (3.12) for underlying high and low back vowels.

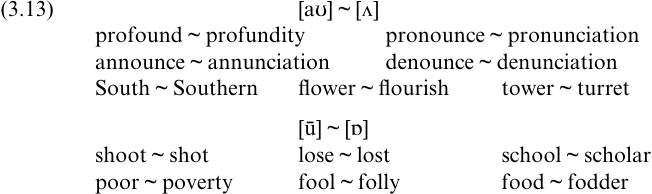

Although /ō/ will regularly lax to [o], and shift to [ɒ] in the verbose ~ verbosity alternation, V̆SR alone is insufficient to derive [aʊ]~[Λ] and [ū] ~ [ɒ]: extra rules are needed to produce [Λ], [ɒ] and [aʊ]. These two alternations were also problematic for `traditional' VSR, and a very small number of alternating pairs is involved (see (3.13)).

It is surely questionable whether the members of these pairs are synchronically related by any productive phonological process, although they may be linked in morphological and/or semantic terms: I return to this point for the strong verbs, lose ~ lost and shoot ~ shot. In profound ~ profundity there is the additional problem of finding an appropriate underlying vowel. If we allow underlying diphthongs, the underlier should clearly be /aʊ/. However, the Vowel Shift derivation proposed above for /aɪ/in divine ~ divinity is not going to work for /aʊ/in profound ~ profundity: /aʊ/, like /aɪ/, would be expected to monophthongize when laxed by losing its second element, since it is a falling diphthong; it would then become [æ] (or [a]) and shift to [ɪ]. Even if, against all the principles of LP, we invented a short low back unrounded [ɑ] for this `back' diphthong to monophthongize to, it would shift to [+high, -low]. To derive [Λ], we must stop the shift half-way, and to derive [ʊ], we need a rounding rule. What this may mean is that this alternation is not part of the Modern English Vowel Shift set. In fact, there are ways of testing this hypothesis.

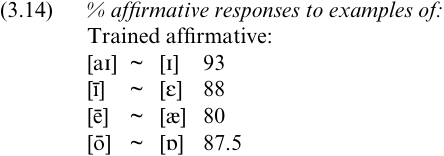

In SPE, the profound ~ profundity and fool ~ folly alternations would result from shifting /u/ and /o/. It is interesting that in Older Scots and other Northern Middle English dialects, /ū/ and /ō/ did not participate in the Great Vowel Shift, suggesting that these may represent in some sense the `weakest' subpart of the Vowel Shift. Psycholinguistic evidence certainly suggests that these alternations are not synchronically characterized using VSR. Several recent experiments which aimed to discover whether speakers `know' the VSR and which alternations they include in the Vowel Shift set have concluded that, while the [aɪ]~[ɪ], [ɪ̄]~[ε], [ē]~ [æ] and [ō] ~ [ɒ] alternations do have some measure of psychological reality for Modern English speakers, [aʊ]~[Λ] and [u]~[ɒ] apparently do not. For instance, in a productivity experiment carried out by Wang (1985), in which speakers were presented with nonsense words as adjectives and required to derive a related noun in-ity, with a shifted vowel, only the alternations [aɪ] ~ [ɪ], [ɪ̄] ~ [ε], [ē] ~ [æ] and [ō] ~ [ɒ] showed any strength. Similar results were obtained in a concept formation experiment reported in Wang and Derwing (1986). Such experiments are designed to ascertain which elements informants perceive as part of a specific group. In this case, speakers were encouraged to form a Vowel Shift concept by answering `yes' to the core Vowel Shift alternations given above, and `no' to `anti-vowel shift' (McCawley 1986) pairs like [aɪ]~[ε] and [ɪ̄] ~ [æ]. The informants were then asked to extend this classification to novel stimuli, and did not respond positively to tokens of the [aʊ] ~ [Λ] and [ū] ~ [ɒ] alternations. In Jaeger's (1986) experiment, speakers' percentage acceptability responses for [aʊ] ~ [Λ] were often lower than for alternations to which they had been trained to respond negatively (see (3.14)).

Although the [aʊ] ~ [Λ] alternation was historically a result of the Great Vowel Shift, at least in the South, the synchronic VSR may no longer include all those vowels that participated in the diachronic change. Wang and Derwing (1986) and McCawley (1986) argue that the Vowel Shift alternations [aɪ] ~ [ɪ], [ɪ̄] ~ [ε], [ē] ~ [æ] and [ō] ~ [ɒ] may be reinforced for Modern English speakers by their correspondence with the English Spelling Rule, since these pairs of vowels are normally spelt <i> , <e> , <a> , and <o> respectively. The synchronic VSR would then be partially orthographically motivated. Jaeger (1986: 86) goes further here, claiming that `the source of speakers' knowledge about these vowel alternations is a combination of orthography and the frequency with which given alternations occur'. If these are indeed the criteria for inclusion of alternations in the synchronic VSR, then [aʊ]~[Λ] and[ū]~[ɒ] clearly fail, since the phonological members of the alternations do not correspond to a single letter in the orthography, and since there are so few examples of the alternations in Present-Day English. Since I argued above that the Modern English vowel system(s) should include underlying diphthongs, we can assume that profound has underlying /aʊ/, profundity /Λ /, fool /ū/,and folly/ɒ/.

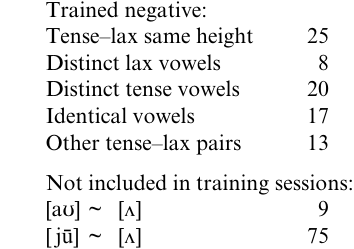

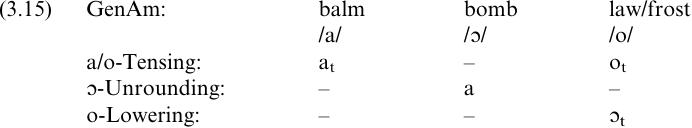

The fool ~ folly alternation brings us to a second contentious area for Vowel Shift, since the pronunciation of the low vowel in folly, and that of other low vowels in glass, balm, frost and law, varies considerably across accents of English. Although Halle and Mohanan (1985) propose common underlying long and short vowel systems for RP and GenAm, they require three special rules, a/o Tensing, O-Unrounding, and o-Lowering, to deal with the divergent realizations of the low vowels in words like balm, bomb and baud. All three rules operate in GenAm, giving the derivations shown in (3.15).

However, Halle and Mohanan contend that only a/o-Tensing applies in RP, producing the truncated derivations of (3.16).

Halle and Mohanan's GenAm derivations in (3.15) preserve a surface contrast of balm [at] and bomb [a]. Wells (1982), however, assumes that underlying /ɒ/ in words of the bomb type is lengthened, tensed and unrounded to merge with the long low unrounded tense /ɑ̄/ of balm words. Wells also asserts that `the result of the merger is phonetically usually a rather long vowel' (1982: 246), although Halle and Mohanan consider their [at] and [a] to be short. Furthermore, they (1985: 101) assign shot and lost underlying /o/, which will tense and lower to [ɔt] in GenAm, although phonetically these words have [ɑ]. This representation is also incorrect for RP, where shot and lost surface with [ɒ], not [ot].

In contrast, I propose that, in RP, balm will have underlying and surface long tense /ɑ̄/ [ɑ̄], bomb/frost short lax /ɒ/ [ɒ], and law long tense /ɔ̄/ [ɔ̄]. Although Halle and Mohanan regard length as the underlying dichotomiser of the English vowel system, with tenseness introduced subsequently during the derivation, I consider long and tense, and short and lax, as present both underlyingly and on the surface. In GenAm, balm will similarly have /ɑ̄/ [ɑ̄], and law/frost, /ɔ̄/ [ɔ̄] (although note that Kurath and McDavid (1961: 7) list various other possible low vowel systems for American varieties, and that diphthongs like [ɔə] may occur in frost words).

The derivation of bomb words in GenAm is not quite so straightforward. If the Halle and Mohanan/SGP assumption of identity of underlying representations is to be maintained, bomb words in GenAm must be assigned underlying /ɒ/, as is the case in RP, with a rule merging /ɒ/ with /ɑ̄/. American varieties in which bomb and balm words are kept distinct, such as the Eastern New England accent included in Kurath and McDavid's (1961: 7) table, will have this variation encoded in the form of the unrounding rule. However, complete underlying identity between RP and GenAm is in any case impossible, given the underlying distributional distinction regarding cough, frost, dog words, which belong with the /ɒ/ class in RP but have /ɔ/ in GenAm. Furthermore, absolute neutralization is clearly involved, jeopardizing the synchronic status of /ɒ/ in GenAm: it is more plausible to omit /ɒ/ from the modern GenAm vowel system, since all words which historically contained /ɒ/ [ɒ] now have either [ɔ̄] (like bomb and stop) or [ɑ̄] (like cough and frost) on the surface. The principle that underlying and lexical representations should be equivalent in non-alternating forms dictates that these lexical sets be represented underlyingly with /ɑ̄/or/ɔ̄/ respectively.

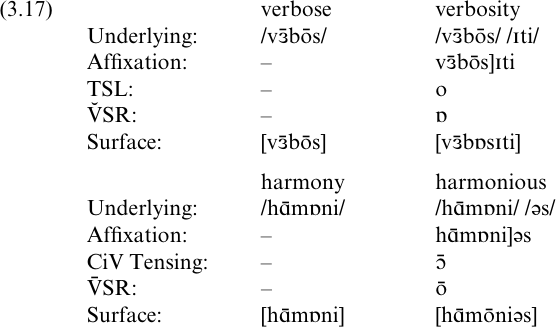

The next question is whether underlying /ɒ/ is motivated in alternating forms like verbose ~ verbosity and harmony ~ harmonious for GenAm. Low back lax rounded /ɒ/ is involved in the derivation of these alternating forms in RP, as shown in (3.17).

There are two points to make here. First, the relevant surface vowel in harmony is in fact reduced, although we might assume that comparison with harmonic justifies underlying /ɒ/. Giegerich (1994) goes further, proposing an underlyingly empty nucleus in alternating forms where the underived surface form has schwa; the appropriate full vowel can be supplied only by reference to independent orthographic representations, and the derivation depends crucially on a structure-building and structure-preserving Spelling Pronunciation rule. I will not pursue this analysis here; it assumes underspecification and is therefore not tenable in my model of LP, although a modified version with underlying schwa and a structure-changing Spelling Pronunciation rule would be compatible with my account of Vowel Shift. Secondly, in GenAm harmonic and verbosity have [ɑ]/[ɑ̄], although verbose and harmonious share surface [o]/ [oʊ] with RP. If we omit /ɒ/ from the GenAm vowel system in alternating forms, how will the Vowel Shift Rules operate?

Let us first turn to verbose ~ verbosity. The input vowel in RP is /ō/, and since this surfaces in both RP and GenAm in verbose, we can assume that /ō/ also underlies this alternation in GenAm. Only one derivational path through VSR is available to /ō/: suffixation of-ity will feed TSL, which in turn will feed V̆SR, producing [ɒ]. In American varieties lacking [ɒ], we must apply an unrounding rule (and subsequently a tensing rule for some subvarieties) to give [ɑ̄]/[ɑ]. This derivation involves [ɒ] only as an intermediate step (and note here Goldsmith's 1990: 224 contention that Structure Preservation may enforce further derivation if a rule application produces some form which does not exist at the underlying level).

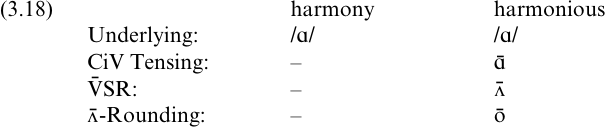

If we assume underlying /ɒ/ for GenAm in harmony ~ harmonious, this will tense and shift to [ō] inharmonious, as in RP, while /ɒ/ in underived harmony must subsequently be unrounded and optionally tensed. This analysis is clearly impermissible in the model developed here, since absolute neutralisation is involved, and the underlying representation will not be equivalent to the lexical representation of the underived form. To maintain this principle, we must assume that the underlying vowel is /ɒ/ in RP, but has been restructured to /ɑ/ in GenAm. This is the only case of apparent cross-dialectal variation in the quality of the input vowel; interestingly, it is also the sole instance where alternative paths through VSR may be available, both producing the same output. The derivational path of /ɒ/ in RP is clear from (3.17); it is tensed in harmonious and subjected to V̄SR, giving [ō]. In GenAm, /ɑ/ would similarly tense to give intermediate [ɑ̄], feeding Vowel Shift as shown in (3.18), with a subsequent rounding rule required to produce surface [ō].

We have not, however, exhausted the issue of the [ɑ̄] vowel of balm, father and, in some varieties of GenAm, bomb. The problematic derivation of this stressed vowel in father, rather, Chicago, ga'rage and balm is familiar from SPE: the father vowel is phonetically long and tense, but does not diphthongize or undergo Vowel Shift. Its underlier must therefore be convertible into the appropriate surface vowel, but also be exempt from VSR and Diphthongization.

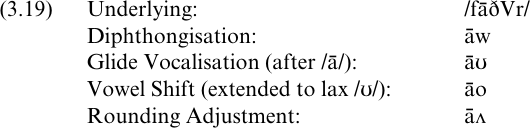

This challenge has produced solutions of varying degrees of credibility. Chomsky and Halle propose underlying tense low back unrounded /ā/, and remove it from the scope of Vowel Shift by restricting the input of this rule to vowels which are [α back, α round]; this condition also excludes /œ/, the SPE source for [ɔɪ]. However, in SPE /ā/ does undergo Diphthongization, receiving a following /w/ glide, which is then vocalized, shifted and unrounded to produce [āΛ] (see (3.19)). This [Λ] may then be realized as `a centering glide of some sort or a feature of extra length' (Chomsky and Halle 1968: 205). The SPE analysis therefore extends the structural description of Rounding Adjustment and allows Vowel Shift, a process historically and otherwise synchronically confined to the long vowel system, to apply to a short lax vowel derived from an offglide; and its product is an exceptional representation whose realization is ambiguous.

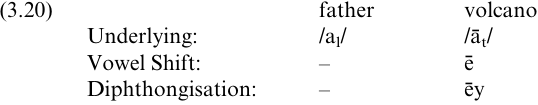

Since Halle (1977) does not allow lax vowels to undergo Vowel Shift, he cannot vocalize and shift glides. However, since father is not phonetically *[fāwðə(r)], Halle must make his underlying vowel an exception to both Vowel Shift and Diphthongization. He does so by modifying the redundancy rule linking length and tenseness in English so that it `admits both tense and lax varieties among long low vowels, but not elsewhere' (Halle 1977: 618). Halle then assigns the underlying long lax vowel /al/to father, Chicago, etc. Diphthongization and Vowel Shift are both sensitive to tenseness, and hence neither will apply to [al], although both will operate on the low tense unrounded vowel /at/, as shown in (3.20). Halle also finds it necessary to reformulate the English Stress Rule so that long, rather than tense vowels will be stressed, to account for the stress on /al/ in Chicago, soprano and so on.

Halle and Mohanan (1985) also exploit discrepancies between length and tenseness in their characterization of the father vowel. However, whereas Halle (1977) proposed a long lax low unrounded vowel, Halle and Mohanan prefer a short tense one. More accurately, they assign short back low unrounded /a/ to father, Chicago, balm underlyingly, but /a/ is then subject to a/o-Tensing, and is said to surface as [āt] in both RP and GenAm. Since Halle and Mohanan restrict the VSR and Diphthongization to long, rather than to tense vowels, /a/ will, as required, be exempted from these rules. They also claim that their analysis allows them to eliminate the feature [± tense] from underlying representations, but since they assume that the Main Stress Rule is also sensitive to length (1985: 76), they are forced to assign a diacritic feature [+accented] to the penultimate syllable of Chicago, sonata, soprano and similar trisyllabic forms to account for their otherwise exceptional stress pattern.

I have already pointed out some difficulties inherent in the SPE account: as for the others, Halle (1977) seems to be using laxness merely as a diacritic to dichotomise instances of the same vowel into Diphthongizing and Shifting versus `static' sets, while Halle and Mohanan, by assigning a short lax underlying vowel to father and Chicago, create difficulties for their stress rules and are also forced to resort to diacritic marking. Furthermore, Halle and Mohanan cannot derive the long vowel pronunciations which are characteristic of the stressed vowel in father, balm, spa and others in American accents and in RP: although they do propose a rule of Long Vowel Tensing (1985: 73), which redundantly tenses all long vowels, they have no mechanism for lengthening tense vowels, and [at] is consequently predicted to surface short.

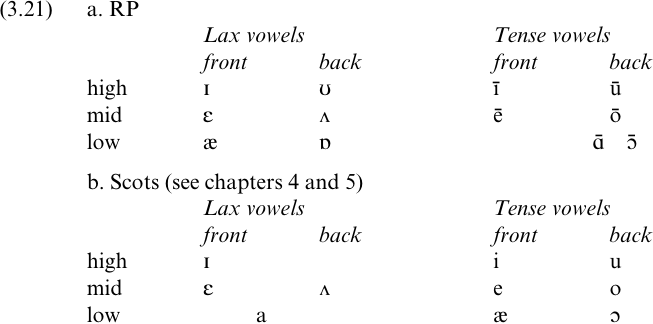

In revising these analyses, it is first important to observe that words like father surface with the back vowel assumed by Chomsky and Halle (1968), Halle (1977) and Halle and Mohanan (1985) in only some accents of English, including GenAm and RP. In many Scots varieties, Australian and New Zealand English, and certain areas of England such as West Yorkshire (see Wells 1982), the father vowel is phonetically front. In a SGP account, these two sets of realizations would be derived synchronically from a single underlying vowel, reflecting the probable historical origin of the divergent forms. However, in LP we are not tied to such an analysis, and I propose therefore that the father vowel should be assigned two distinct underliers: these will be back /ɑ̄/ in accents like RP and GenAm with a phonetically back vowel in father words, and front /ǣ/ in those accents where the surface vowel is front. Short lax /a/ (from Halle's system) and long lax /ɔl/, /al/ (from Halle and Mohanan's) will be eliminated from all underlying English vowel systems, and the perfect correlation of length and tenseness which was disturbed by Halle's and Halle and Mohanan's treatment of the father vowel will be restored. Two sample systems are given in (3.21): the back unrounded vowels /ɨ̄ Ɨ̄ Λ̄/ which figure in Halle and Mohanan's system are omitted until 3.4 below.

Nor, in the model presented here, need these low vowels be exempted from Vowel Shift or Diphthongization. First, recall that I have argued against the Diphthongization rule; all varieties of English will now include some underlying diphthongs, most generally /aɪ aʊ ɔɪ/. Furthermore, the revised lax- and tense-vowel VSRs will never affect underlying vowels: that is, VSR can never be the first phonological rule to apply to a vowel, since it must be fed by a tensing or laxing rule to satisfy DEC. Underlying /ǣ/ will no longer appear in any word involved in a VSR alternation: sane ~ sanity will have underlying /ē/, while divine ~ divinity show [aɪ]~[ɪ] derived from /aɪ/. Underlying /ǣ/or/ɑ̄/ in father, Chicago, spa therefore require no special exclusion from V̄SR, since all the father words will constitute underived environments for both Vowel Shift Rules, so that the relevant vowel will be low underlyingly and throughout the derivation. Only in some American accents might /ɑ̄/ appear in suitable alternating forms like harmonic ~ harmonious; the resulting derivation was outlined earlier, and has no consequences for the treatment of non-alternating father.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|