Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The rarity of borrowed inflectional morphology

المؤلف:

Andrew Carstairs-McCarthy

المصدر:

An Introduction To English Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

102-9

2024-02-05

2061

The rarity of borrowed inflectional morphology

One way in which a root can avoid appearing naked is if it is accompanied by an inflectional affix. At first sight, then, it may seem that, if English borrows a foreign pattern of word formation, it should be expected to borrow inflectional affixes that conform to that pattern, as well as roots and derivational affixes. In fact, this scarcely happens; English does not use French or Latin inflectional affixes on verbs borrowed from those languages, for example. However, this is not so surprising when one bears in mind that the new items that a language acquires through borrowing are lexemes rather than individual word forms, for reasons that I will explain.

If English speakers import a new verb V from French, they will not import just its past tense form (say), since we expect to be able to express in English not only the grammatical word ‘past tense of V’ but also the grammatical words ‘third person singular present of V’, ‘perfect participle of V’, and so on. But it is not convenient for English speakers to pick these word forms out of the repertoire of forms that V has in French, partly because that presupposes a knowledge of French grammar, and partly because there may be no French grammatical word exactly corresponding to ‘third person singular present’, ‘perfect participle’, and so on. It is much more convenient to equip the new French-sourced verb with word forms created in accordance with English verbal inflection – specifically, the most regular pattern of verbal inflection (suffixes -s, -ed and -ing). And that is precisely what happens.

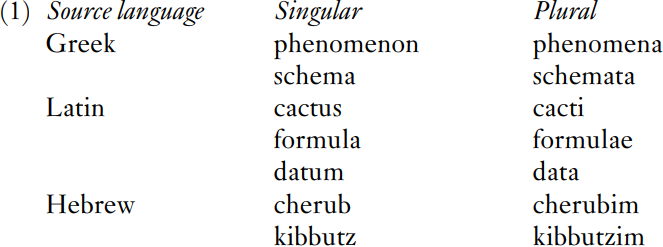

The only condition under which English speakers are likely to borrow foreign word forms along with the lexemes that they belong to is if the grammatical words that the word forms express are few in number (and thus not hard to learn), and if their functions in English and the source language correspond closely. This condition is fulfilled with nouns. English nouns have only two forms, singular and plural; and, if a noun is borrowed from a source language that also distinguishes singular and plural inflectionally, then the foreign inflected plural form may be borrowed too. Here are some examples involving Latin, Greek and Hebrew, which resemble English in distinguishing singular and plural forms in nouns:

These foreign plurals are all vulnerable, however. Phenomena and data seem solidly established, but for the others it is probably more usual now to hear or read schemas, cactuses, formulas, cherubs and kibbutzes. Even data tends to be accommodated to English morphology, but by a different method: many speakers treat it not as plural (these data are …) but as singular (this data is …), and the corresponding singular form datum tends to be replaced by piece of data (rather like piece of toast in relation to toast).

(You may wonder why I have not mentioned French as a source for borrowed plural inflection, given the importance of the French component in English vocabulary. The reason is that the usual plural suffix in both medieval and modern French is -s, just as in English. A plural word form borrowed from French would therefore nearly always be indistinguishable from one inflected in the regular English fashion. Just a few French borrowings sometimes retain, in formal written English, an idiosyncratic plural suffix -x, e.g. tableaux, plateaux.)

The effect of these borrowings is to divide the class of nouns with irregular plurals (i.e. plurals not involving -s) into two classes: nouns that belong to everyday vocabulary and whose irregular plural survives because it is in reasonably frequent use (e.g. teeth, children, mice), and relatively rare or technical nouns whose irregular plural survives (if at all) as a badge of learning or sophistication. What we do not find are irregular plurals that fall between these extremes, in nouns that are not particularly common but do not belong to technical or learned vocabulary either. (At first sight, an example of this kind may seem to be oxen, the plural of the noun ox; but, in English-speaking countries where the dominant religion is Christianity, this unusual plural form is almost certainly kept alive by its occurrence in the Gospel Nativity story.)

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)