تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

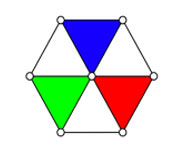

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

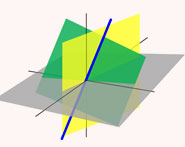

الهندسة

الهندسة

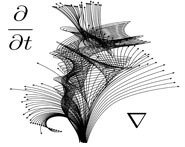

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 22-10-2015

Date: 21-10-2015

Date: 22-10-2015

|

Born: 1364 in Bursa, Turkey

Died: 1436 in Samarkand, Uzbekistan

Qadi Zada means "son of the judge" and we must assume that indeed Qadi Zada's father was the judge. Qadi Zada, however, is not his proper name which was Salah al-Din Musa Pasha. While we are commenting on his name we should also note that it is often written as Qadizada. Dilgan points out in [1] that certain historians have made errors regarding Qadi Zada's name. For example Montucla says that he was a Greek convert to Islam which Dilgan suggests may come from a misunderstanding of the name al-Rumi [1]:-

... for the peoples who lived in Asia Minor were called Rum, meaning Roman (not Greek), because Asia Minor was once Roman.

It was in his home town of Bursa that Qadi Zada was brought up. He completed his standard education in Basra and then studied geometry and astronomy with al-Fanari. His teacher al-Fanari realised that Qadi Zada was a young man with great abilities in mathematics and astronomy and he advised him to visit the cultural centres of the empire, Khorasan or Transoxania, where he could benefit from coming in contact with the top mathematicians of his time.

When Qadi Zada was a young man, Timur, who is often known as Tamerlane, ruled the empire stretching across present day Iran, Iraq, and eastern Turkey. After Timur's death in 1405, his empire was disputed among his sons. Shah Rukh was the fourth son of Timur and, by 1407, he had gained overall control of most of the empire, including Iran and Turkistan, regaining control of Samarkand. The cultural centres where Qadi Zada would be advised to visit would include Herat in Khorasan (today in western Afghanistan) and Bukhara and Samarkand in Transoxania.

It was not until around 1407 that Qadi Zada set off to visit these cities. It is unclear why he waited so long for by this time he was over forty years of age, not really a young man setting off to begin a career. He had already gained a good reputation as a mathematician and a treatise on arithmetic, which he composed in Bursa in 1383, has survived. It is a work which covers arithmetic, algebra and mensuration.

After visiting a number of cities, Qadi Zada reached Samarkand in about 1410. The previous year Shah Rukh, having gained control of his father Timur's empire, had decided to make Herat in Khorasan his new capital and put his own son Ulugh Beg in control of Samarkand. Ulugh Beg was only 17 years old when Qadi Zada met him at Samarkand in 1410. He was far more interested in science and culture than in politics or military conquest but he was, nevertheless, deputy ruler of the whole empire and, in particular, sole ruler of the Mawaraunnahr region. Meeting Ulugh Beg was certainly a turning point for Qadi Zada, for he would spend the rest of his life working in Samarkand. He married in that city and his son Shams al-Din Muhammad was born there.

Qadi Zada wrote a number of commentaries on works on mathematics and astronomy during his first years in Samarkand. These seem to have been written for Ulugh Beg and it would appear that Qadi Zada was producing material as a teacher of the brilliant young mathematician. One commentary on the compendium of the astronomer al-Jaghmini was written by Qadi Zada in 1412-13, while a second commentary was on a work by al-Samarqandi. This second commentary is on al-Samarqandi's famous short work of only 20 pages in which he discusses thirty-five of Euclid's propositions. Qadi Zada wrote the work in 1412.

In 1417, perhaps encouraged by Qadi Zada, Ulugh Beg began building a madrasah which is a centre for higher education. The madrasah, fronting the Rigestan Square in Samarkand, was completed in 1420 and Ulugh Beg then began to appoint the best scientists he could find to teaching positions in his university. In addition to Qadi Zada, Ulugh Beg invited al-Kashi to join his madrasah, as well as around sixty other scientists. There is little doubt that al-Kashi, Qadi Zada and Ulugh Beg himself, were the leading astronomers and mathematicians at this prestigious establishment in Samarkand.

Construction of an observatory in Samarkand began in 1424 and, while the observatory was under construction, al-Kashi wrote to his father, who lived in Kashan, about the scientific life in Samarkand. In the letters al-Kashi praises the mathematical abilities of Ulugh Beg and Qadi Zada but considers the other scientist second rate compared with them. Scientific meetings were led by Ulugh Beg and in these sessions problems in astronomy were freely discussed. Usually these problems were too difficult for all except al-Kashi and Qadi Zada.

Qadi Zada's most original work was a computation of sin 1° with remarkable accuracy. He published his methods in his Treatise in the sine and, although al-Kashi also produced a method for solving this problem, the two methods are different and show that two remarkable scientists were both working on the same problems at Samarkand. Qadi Zada computed sin 1° to an accuracy of 10-12 (if expressed in decimals), as did al-Kashi. The method is fully described in [1] (see also [5]).

The major work undertaken at the Observatory in Samarkand was the production of the Catalogue of the stars, the first comprehensive stellar catalogue since that of Ptolemy. This star catalogue, the Zij-i Sultani, set the standard for such works up to the seventeenth century. Published in 1437, in the year following Qadi Zada's death, it gives the positions of 992 stars. The catalogue was a collaborative effort by a number of scientists working at the Observatory but the principal contributors were certainly Ulugh Beg, al-Kashi, and Qadi Zada. As well as tables of observations made at the Observatory, the work contained calendar calculations and results in trigonometry.

A commentary by Qadi Zada which is incomplete, was on the astronomical treatise of Nasir ad-Din al-Tusi. The contents of this surviving work are described in [3]. A treatise by Qadi Zada on the problem of facing Mecca, an important problem which many Muslim astronomers and mathematicians discussed, has also survived.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|