Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-07-13

Date: 2-2-2022

Date: 2023-09-26

|

In contrast to the taxonomic approach adopted in traditional grammar, Chomsky takes a cognitive approach to the study of grammar. For Chomsky, the goal of the linguist is to determine what it is that native speakers know about their native language which enables them to speak and understand the language: hence, the study of language is part of the wider study of cognition (i.e. what human beings know). In a fairly obvious sense, any native speaker of a language can be said to know the grammar of his or her native language. For example, any native speaker of English can tell you that the negative counterpart of I like syntax is I don’t like syntax, and not e.g. ∗I no like syntax: in other words, native speakers know how to combine words together to form expressions (e.g. negative sentences) in their language. Likewise, any native speaker of English can tell you that a sentence like She loves me more than you is ambiguous and has two interpretations which can be paraphrased as ‘She loves me more than she loves you’ and ‘She loves me more than you love me’: in other words, native speakers also know how to interpret (i.e. assign meaning to) expressions in their language. However, it is important to emphasize that this grammatical knowledge of how to form and interpret expressions in your native language is tacit (i.e. subconscious) rather than explicit (i.e. conscious): so, it’s no good asking a native speaker of English a question such as ‘How do you form negative sentences in English?’, since human beings have no conscious awareness of the processes involved in speaking and understanding their native language. To introduce a technical term devised by Chomsky, we can say that native speakers have grammatical competence in their native language: by this, we mean that they have tacit knowledge of the grammar of their language – i.e. of how to form and interpret words, phrases and sentences in the language.

In work dating back to the 1960s, Chomsky has drawn a distinction between competence (the native speaker’s tacit knowledge of his or her language) and performance (what people actually say or understand by what someone else says on a given occasion). Competence is ‘the speaker–hearer’s knowledge of his language’, while performance is ‘the actual use of language in concrete situations’ (Chomsky 1965, p. 4). Very often, performance is an imperfect reflection of competence: we all make occasional slips of the tongue, or occasionally misinterpret something which someone else says to us. However, this doesn’t mean that we don’t know our native language or that we don’t have competence in it. Misproductions and misinterpretations are performance errors, attributable to a variety of performance factors like tiredness, boredom, drunkenness, drugs, external distractions and so forth. A grammar of a language tells you what you need to know in order to have native-like competence in the language (i.e. to be able to speak the language like a fluent native speaker): hence, it is clear that grammar is concerned with competence rather than performance. This is not to deny the interest of performance as a field of study, but merely to assert that performance is more properly studied within the different – though related – discipline of psycholinguistics, which studies the psychological processes underlying speech production and comprehension.

In the terminology adopted by Chomsky (1986a, pp. 19–56), when we study the grammatical competence of a native speaker of a language like English we’re studying a cognitive system internalized within the brain/mind of native speakers of English; our ultimate goal in studying competence is to characterize the nature of the internalized linguistic system (or I-language, as Chomsky terms it) which makes native speakers proficient in English. Such a cognitive approach has obvious implications for the descriptive linguist who is concerned to develop a grammar of a particular language like English. According to Chomsky (1986a, p. 22) a grammar of a language is ‘a theory of the I-language . . . under investigation’. This means that in devising a grammar of English, we are attempting to uncover the internalized linguistic system (= I-language) possessed by native speakers of English – i.e. we are attempting to characterize a mental state (a state of competence, and thus linguistic knowledge). See Smith (1999) for more extensive discussion of the notion of I-language.

Chomsky’s ultimate goal is to devise a theory of Universal Grammar/UG which generalizes from the grammars of particular I-languages to the grammars of all possible natural (i.e. human) I-languages. He defines UG (1986a, p. 23) as ‘the theory of human I-languages . . . that identifies the I-languages that are humanly accessible under normal conditions’. (The expression ‘are humanly accessible’ means ‘can be acquired by human beings’.) In other words, UG is a theory about the nature of possible grammars of human languages: hence, a theory of UG answers the question: ‘What are the defining characteristics of the grammars of human I-languages?’

There are a number of criteria of adequacy which a theory of Universal Grammar must satisfy. One such criterion (which is implicit in the use of the term Universal Grammar) is universality, in the sense that a theory of UG must supply us with the tools needed to provide a descriptively adequate grammar for any and every human I-language (i.e. a grammar which correctly describes how to form and interpret expressions in the relevant language). After all, a theory of UG would be of little interest if it enabled us to describe the grammar of English and French, but not that of Swahili or Chinese.

However, since the ultimate goal of any theory is explanation, it is not enough for a theory of Universal Grammar simply to list sets of universal properties of natural language grammars; on the contrary, a theory of UG must seek to explain the relevant properties. So, a key question for any adequate theory of UG to answer is: ‘Why do grammars of human I-languages have the properties they do?’ The requirement that a theory should explain why grammars have the properties they do is conventionally referred to as the criterion of explanatory adequacy.

Since the theory of Universal Grammar is concerned with characterizing the properties of natural (i.e. human) I-language grammars, an important question which we want our theory of UG to answer is: ‘What are the defining characteristics of human I-languages which differentiate them from, for example, artificial languages like those used in mathematics and computing (e.g. Java, Prolog, C etc.), or from animal communication systems (e.g. the tail-wagging dance performed by bees to communicate the location of a food source to other bees)?’ It therefore follows that the descriptive apparatus which our theory of UG allows us to make use of in devising natural language grammars must not be so powerful that it can be used to describe not only natural languages, but also computer languages or animal communication systems (since any such excessively powerful theory wouldn’t be able to pinpoint the criterial properties of natural languages which differentiate them from other types of communication system). In other words, a third condition which we have to impose on our theory of language is that it be maximally constrained: that is, we want our theory to provide us with technical devices which are so constrained (i.e. limited) in their expressive power that they can only be used to describe natural languages, and are not appropriate for the description of other communication systems. A theory which is constrained in appropriate ways should enable us to provide a principled explanation for why certain types of syntactic structure and syntactic operation simply aren’t found in natural languages. One way of constraining grammars is to suppose that grammatical operations obey certain linguistic principles, and that any operation which violates the relevant principles leads to ungrammaticality: see the discussion below in §1.5 for a concrete example.

A related requirement is that linguistic theory should provide grammars which make use of the minimal theoretical apparatus required: in other words, grammars should be as simple as possible. Much earlier work in syntax involved the postulation of complex structures and principles: as a reaction to the excessive complexity of this kind of work, Chomsky in work over the past ten years or so has made the requirement to minimize the theoretical and descriptive apparatus used to describe language the cornerstone of the Minimalist Program for Linguistic Theory which he has been developing (in work dating back to Chomsky 1993, 1995). In more recent work, Chomsky (1998, 1999, 2001, 2002) has suggested that language is a perfect system with an optimal design in the sense that natural language grammars create structures which are designed to interface perfectly with other components of the mind – more specifically with speech and thought systems. (For discussion of the idea that language is a perfect system of optimal design, see Lappin, Levine and Johnson 2000a,b, 2001; Holmberg 2000; Piattelli-Palmarini 2000; Reuland 2000, 2001b; Roberts 2000, 2001a; Uriagereka 2000, 2001; Freidin and Vergnaud 2001; and Atkinson 2003.)

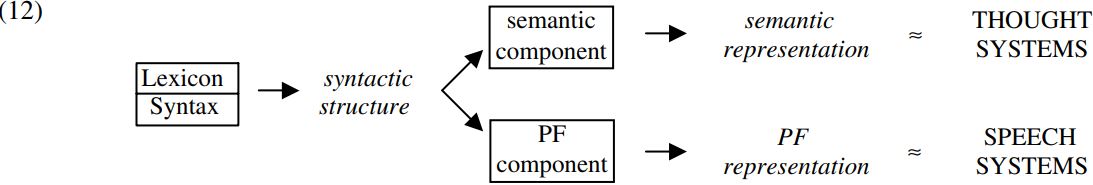

To make this discussion rather more concrete, let’s suppose that a grammar of a language is organized as follows. One component of a grammar is a Lexicon (= dictionary = list of all the lexical items/words in the language and their linguistic properties), and in forming a given sentence out of a set of words, we first have to take the relevant words out of the Lexicon. Our chosen words are then combined together by a series of syntactic computations in the syntax (i.e. in the syntactic/computational component of the grammar), thereby forming a syntactic structure. This syntactic structure serves as input into two other components of the grammar. One is the semantic component which maps (i.e. ‘converts’) the syntactic structure into a corresponding semantic representation (i.e. to a representation of linguistic aspects of its meaning); the other is a PF component, so called because it maps the syntactic structure into a PF representation (i.e. a representation of its Phonetic Form, telling us how it is pronounced). The semantic representation interfaces with systems of thought, and the PF representation with systems of speech – as shown in diagrammatic form below:

In terms of the model in (12), an important constraint is that the (semantic and PF) representations which are ‘handed over’ to the (thought and speech) interface systems should contain only elements which are legible by the appropriate interface system – so that the semantic representations handed over to thought systems contain only elements contributing to meaning, and the PF representations handed over to speech systems contain only elements which contribute to phonetic form (i.e. to determining how the sentence is pronounced).

The neurophysiological mechanisms which underlie linguistic competence make it possible for young children to acquire language in a remarkably short period of time. Accordingly, a fourth condition which any adequate linguistic theory must meet is that of learnability: it must provide grammars which are learnable by young children in a short period of time. The desire to maximize the learnability of natural language grammars provides an additional argument for minimizing the theoretical apparatus used to describe languages, in the sense that the simpler grammars are, the simpler it is for children to acquire them.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

بمساحة تزيد على (4) آلاف م²... قسم المشاريع الهندسية والفنية في العتبة الحسينية يواصل العمل في مشروع مستشفى العراق الدولي للمحاكاة

|

|

|