Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Reflection: Production footing beyond the speaker

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

123-5

11-5-2022

759

Reflection: Production footing beyond the speaker

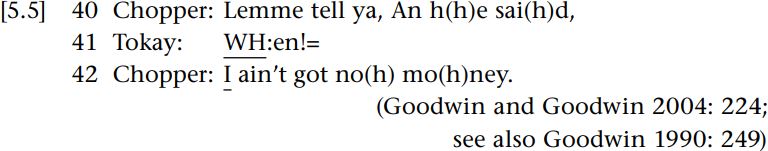

The different production roles are not limited, however, to speakers per se. In some instances, talk may depict someone who is co-present or involve attributing utterances to others (including others who are co-present). Let us consider the following example taken from a recording of conversation amongst some (African-American) children in the United States, where Chopper has just been asked what Tony said when confronted by a group of boys on the street.

In lines 40 and 42, Chopper is attributing an utterance to Tony, namely, I ain’t got no money. This means that although Chopper is the animator (or utterer) here, the figure is Tony. Thus, me in line 40 refers to Chopper, while I in line 42 refers to Tony, even though they’re part of one and the same utterance. It also means Tony is the author and principal of the utterance quoted (at least so Chopper alleges). However, there are also laughter particles interspersed through this quotation of what was said by Tony. These laughter particles are attributable to Chopper, who is therefore the author and principal for what is implicated by attributing this statement to Tony, namely, that Tony is a coward. Through this laughter, Chopper also implicates that this is a laughable matter, both in the sense of laughing at what was said by Tony, as well as at Tony himself. Since Tony (the figure) is also present during this telling, he also becomes a target of the derision that arises through what is implicated here. In analyzing the speaker meaning that arises in this case, then, we have two distinct footings: that of Chopper as the animator as well as the author and principal of what is implicated, and Tony as the author and principal of what is said.

A consideration of production roles opens up many interesting questions about the nature of speaker meaning, and a more nuanced understanding of whose meaning representation we are analyzing, as earlier noted by Bertuccelli-Papi (1999). There is also, however, the issue of participation status to be considered, or what might be termed reception roles (Levinson 1988). Goffman (1981) made a distinction between recipients who are ratified and those who are not. This was based on the intuitive distinction we can draw in English between hearing and listening, where the latter entails some responsibility to respond to or participate in the talk, even if that only means showing one is paying attention to the talk and not something else. A ratified recipient (or participant) is an individual who is expected to not only hear but also listen to the talk. An unratified recipient (or non-participant) is an individual who can hear the talk but is not expected to listen. These two types of recipients, or participants, were further subdivided by Goffman into different footings. A participant may either be an addressee or an unaddressed side participant. An addressee is a person (or persons) to whom the utterance is (ostensibly) directed, but both addressees and side participants have recognized entitlements to respond to the utterance, although their degree of responsibility to do so varies (at least ostensibly). Unratified recipients, or non-participants, on the other hand can be divided, following Verschueren (1999: 82–86) into bystanders and overhearers. The former encompasses a person (or persons) that can be expected to be able to hear at least some parts of the talk, but is not ratified as a participant. A waiter who is standing next to a table while guests talk in a restaurant can be considered a bystander, for instance. An overhearer, on the other hand, refers to a person (or persons) that might be able to hear some parts of the talk. Overhearers include listener-ins, that is, persons who are in view, such as guests at an adjoining table in the restaurant, and eavesdroppers, that is, persons who are secretly following the talk.

There is experimental work that has demonstrated that the understandings of participants and non-participants cannot be assumed to be synonymous, even in situations where the non-participants can hear everything that is said by the participants (Schober and Clark 1989). In their experiments, Schober and Clark (1989) examined the understandings of addressees (the participants) of conversations between strangers about an unfamiliar topic versus the understandings of eavesdroppers (the non-participants) of those conversations. They found that the eavesdroppers’ understanding of the conversation was significantly less than that of the addressees, despite the former having full access to all the same utterances, and sharing the same common ground as that existing between the participants, since they were all strangers in both cases. This shows that we cannot assume different recipients will all reach the same understandings of meanings arising in a particular conversation. In other words, depending on one’s reception footing, a person’s understanding of pragmatic meaning may vary.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)