Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 15-3-2022

Date: 21-3-2022

Date: 2024-02-20

|

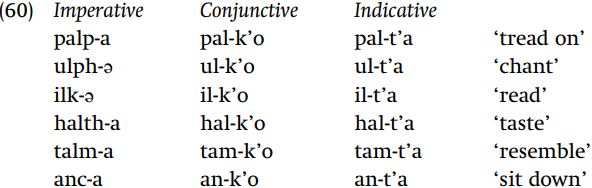

A second major class of phonological processes can be termed “prosodically motivated processes.” Such processes have an effect on the structure of the syllable (or higher prosodic units such as the “foot”), usually by inserting or deleting a consonant, or changing the status of a segment from vowel to consonant or vice versa.

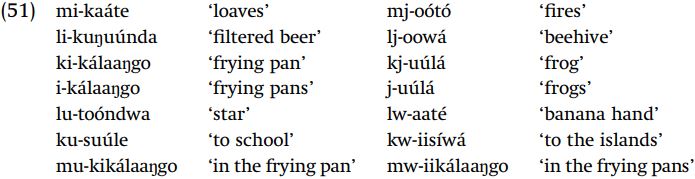

Vowel sequences. A very common set of prosodic processes is the class of processes which eliminate V+V sequences. Many languages disallow sequences of vowels, and when such sequences would arise by the combination of morphemes, one of the vowels is often changed. One of the most common such changes is glide formation, whereby a high vowel becomes a glide before another vowel. Quite often, this process is accompanied with a lengthening of the surviving vowel, a phenomenon known as compensatory lengthening. For example, in Matuumbi, high vowels become glides before other vowels, as shown by the data in (51). The examples on the left show that the noun prefixes have underlying vowels, and those on the right illustrate application of glide formation.

Although the stem-initial vowel is long on the surface in these examples, underlyingly the vowel is short, as shown when the stem has no prefix or when the prefix vowel is a. Thus, compare ka-ótó ‘little fire,’ ma-owá ‘beehives,’ ka-úlá little frog,’ até ‘banana hands,’ ipʊkʊ́ ‘rats.’

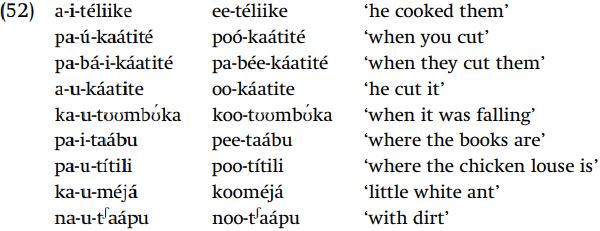

Vowel sequences can also be eliminated by coalescing the two vowels into a single vowel, often one which preserves characteristics of the individual vowel. This happens in Matuumbi as well, where the combinations /au/ and /ai/ become [oo] and [ee]. This rule is optional in Matuumbi, so the uncoalesced vowel sequence can also be pronounced (thus motivating the underlying representation).

The change of /au/ and /ai/ to [oo] and [ee] can be seen as creating a compromise vowel, one which preserves the height of the initial vowel /a/, and the backness and roundness of the second vowel.

Sometimes, vowel sequences are avoided simply by deleting one of the vowels, with no compensatory lengthening. Thus at the phrasal level in Makonde, word-final /a/ deletes before an initial vowel, cf. lipeeta engaanga ! lipeet engaanga ‘the knapsack, cut it!’, likuka engaanga ! likuk engaanga ‘the trunk, cut it!’, nneemba idanaao ! nneemb idanaao ‘the boy bring him!’.

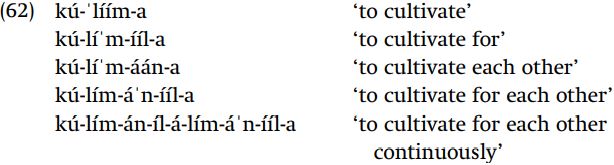

Vowel epenthesis. The converse process of vowel epenthesis is also quite common. One context that often results in epenthesis is when an underlying form has too many consonants in a row, given the syllable structure of the language. Insertion of a vowel then reduces the size of the consonant cluster. An example of such epenthesis is found in Fula. In this language, no more than two consonants are allowed in a row. As the data of (53) show, when the causative suffix /-na/ is added to a stem ending in two consonants, the vowel i is inserted, thus avoiding three consecutive consonants.

Another form of vowel epenthesis is one that eliminates certain kinds of consonants in a particular position. The only consonants at the end of the word in Kotoko are sonorants, so while the past tense of the verbs in (54a) is formed with just the stem, the verbs in (54b) require final epenthetic schwa.

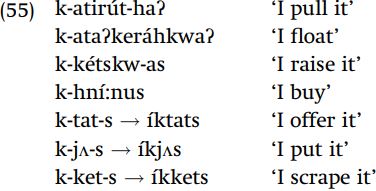

Another factor motivating epenthesis is word size, viz. the need to avoid monosyllabic words. One example is seen in the following data from Mohawk, where the first-singular prefix is preceded by the vowel í only when it is attached to a monosyllabic stem.

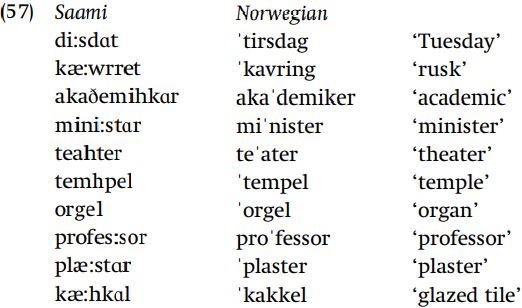

The adaptation of loanwords into North Saami from Scandinavian languages (Norwegian or Swedish) illustrates a variant on the Mohawk-type minimal-word motivation for epenthesis. In this case, a vowel is inserted to prevent a monosyllabic stress foot – though interestingly this requirement is determined on the basis of the Norwegian source, whereas in the Saami word stress is (predictably) on the first syllable. Except for a small set of “special” words (pronouns, grammatical words), words in Saami must be at least two syllables long. Thus the appearance of a final epenthetic vowel in the following loanwords is not surprising.

In contrast, in the following loanwords there is no epenthetic vowel. The location of stress, which is the key to understanding this problem, is marked on the Norwegian source though stress is not marked in the orthography.

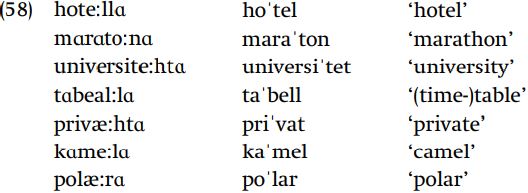

The above examples are ambiguous in analysis, since the source word is both polysyllabic and has a nonfinal stress. The examples in (58), on the other hand, show epenthesis when the stress-foot in the source word is monosyllabic, even though the overall word is polysyllabic.

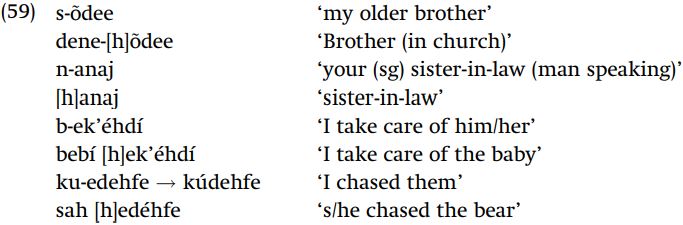

Onset creation. Consonants can also be inserted. The main cause of consonant insertion is the avoidance of initial vowels or vowel sequences. In Arabic all syllables begin with a consonant, and if a word has no underlying initial consonant a glottal stop is inserted, thus /al-walad/ ! [ʔalwalad] ‘the boy.’ In the Hare and Bearlake dialects of Slave, words cannot begin with a vowel, so when a vowel-initial root stands at the beginning of a word (including in a compound), the consonant h is inserted.

In Axininca Campa t is inserted between vowels – this language does not have a glottal stop phoneme. Thus, /i-N-koma-i/ ! [inkomati] ‘he will paddle.’

Cluster reduction. Deletion of consonants can be found in languages. The most common factor motivating consonant deletion is the avoidance of certain kinds of consonant clusters – a factor which also can motivate vowel epenthesis. Consonant cluster simplification is found in Korean.

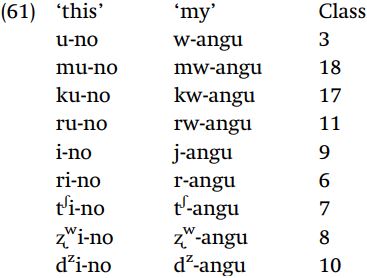

Another cause of cluster simplification is the avoidance of certain specific types of consonant clusters. Shona avoids clusters of the form Cj, although Cw is perfectly acceptable. The deletion of j after a consonant affects the form of possessive pronouns in various noun classes. Demonstratives and possessive pronouns are formed with an agreement prefix reflecting the class of the noun, plus a stem, -no for ‘this’ and -angu for ‘my.’ Before the stem -angu, a high vowel becomes a glide. Where this would result in a Cy sequence, the glide is deleted.

Since /i-angu/ becomes jangu, it is evident that the vowel i does become a glide before a vowel rather than uniformly deleting.

Stress lengthening and reduction. Processes lengthening stressed vowels are also rather common. An example of stress-induced vowel lengthening is found in Makonde, where the penultimate syllable is stressed, and the stressed vowel is always lengthened.

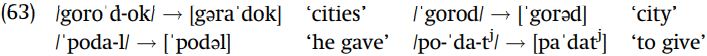

A related process is the reduction of unstressed vowels, as found in English. From alternations like bəˈrɔmətr ~ ˌbɛrəˈmɛtrιk, ˈmɔnəpowl ~ məˈnɔpəlij, we know that unstressed vowels in English are reduced to schwa. Russian also reduces unstressed nonhigh vowels so that /a, o/ become [ə], or [a] in the syllable immediately before the stress.

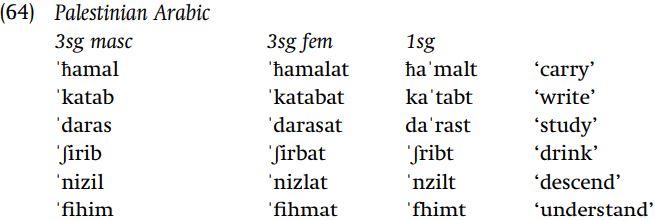

Reduction of unstressed vowels can go all the way to deletion, so in Palestinian Arabic, unstressed high vowels in an open syllable are deleted.

Syllable weight limits. Many languages disallow long vowels in syllables closed by consonants, and the following examples from Yawelmani show that this language enforces such a prohibition against VVC syllables by shortening the underlying long vowel.

A typical explanation for this pattern is that long vowels contribute extra “weight” to a syllable (often expressed as the mora), and syllable-final consonants also contribute weight. Languages with restrictions such as those found in Yawelmani are subject to limits on the weight of their syllables.

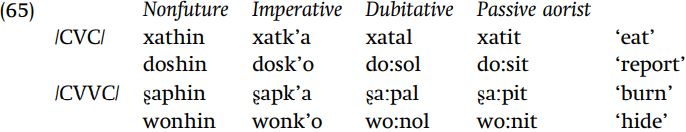

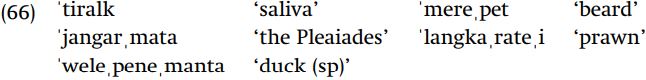

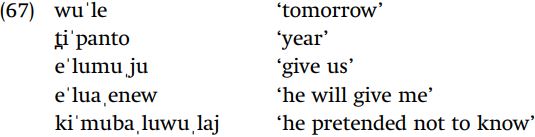

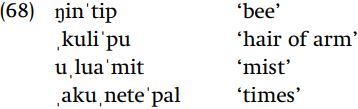

Stress patterns. Stress assignment has been the subject of intensive typological study and has proven a fruitful area for decomposing phonological parameters. See Hayes (1995) for a survey of different stress systems. One very common stress assignment pattern is the alternating pattern, where every other syllable is assigned a stress. Maranungku exemplifies this pattern, where the main stress is on the first syllable and secondary stresses are on all subsequent odd-numbered syllables.

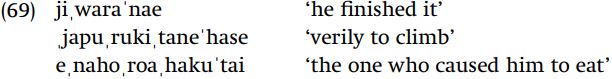

A variant of this pattern occurs in Araucanian, where the main stress appears on the second syllable, and secondary stresses appear on every even-numbered syllable following.

The mirror image of the Maranugku pattern is found in Weri, where the last syllable has the main stress and every other syllable preceding has secondary stress.

Finally, Warao places the main stress on the penultimate syllable and has secondary stresses on alternating syllables before.

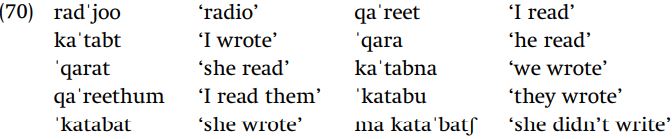

Another property exhibited by many stress systems is quantity-sensitivity, where stress is assigned based on the weight of a syllable. Palestinian Arabic has such a stress system, where stress is assigned to the final syllable if that syllable is heavy, to the penult if the penult is heavy and the final syllable is light, and to the antepenult otherwise. The typical definition of a heavy syllable is one with either a long vowel or a final consonant; however, it should be noted that in Arabic, final syllables have a special definition for “heavy,” which is that a single consonant does not make the syllable heavy, but two consonants do.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|