Glass formation

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص623-624

الجزء والصفحة:

ص623-624

2025-10-11

2025-10-11

250

250

Glass formation

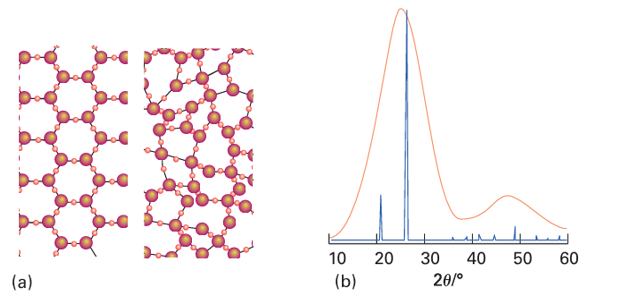

Key points: Silicon dioxide readily forms a glass because the three-dimensional network of strong covalent Si–O bonds in the melt does not easily break and reform on cooling; the Zachariasen rules summarize the properties likely to lead to glass formation. A glass is prepared by cooling a melt more quickly than it can crystallize. Cooling molten silica, for instance, gives vitreous quartz. Under these conditions the solid has no long-range order as judged by the lack of X-ray diffraction peaks, but spectroscopic and other data indicate that each Si atom is surrounded by a tetrahedral array of O atoms. The lack of long-range order results from variations of the Si-O-Si angles. Figure 24.31a illustrates in two dimensions how a local coordination environment can be preserved but long-range order lost by variation of the bond angles around O. This loss of long-range order is readily apparent when X-rays are scattered from a glass (Fig. 24.31b); in contrast to a long-range, periodically ordered crystalline material, where diffraction gives rise to a series of diffraction maxima (Section 8.1), the X-ray diffraction pattern obtained from a glass shows only broad features as the long-range order is lost. Silicon dioxide readily forms a glass because the three-dimensional network of strong covalent Si-O bonds in the melt does not readily break and reform on cooling. The lack of strong directional bonds in metals and simple ionic substances makes it much more difficult to form glasses from these materials. Recent ly, however, techniques have been developed for ultrafast cooling and, as a result, a wide variety of metals and simple inorganic materials can now be frozen into a vitreous state. The concept that the local coordination sphere of the glass-forming element is preserved but that bond angles around O are variable was originally proposed by W.H. Zachariasen in 1932. He reasoned that these conditions would lead to similar molar Gibbs energies and molar volumes for the glass and its crystalline counterpart. Zachariasen also proposed that the vitreous state is favoured by polyhedral corner-sharing O atoms, rather than edge- or face-shared, which would enforce greater order. These and other Zachariasen rules hold for common glass-forming oxides, but exceptions are known.

An instructive comparison between vitreous and crystalline materials is seen in their change in volume with temperature (Fig. 24.32). When a molten material crystallizes, an abrupt change in volume (usually a decrease) occurs. By contrast, a glass-forming material that is cooled sufficiently rapidly persists as a metastable supercooled liquid. When cooled below the glass transition temperature Tg, the supercooled liquid becomes rigid, and this change is accompanied by only an inflection in the cooling curve rather than an abrupt change in slope. The rates of crystallization are very slow for many complex metal silicates, phosphates, and borates, and it is these compounds that often form glasses.

Figure 24.31 (a) Schematic representation of a two-dimensional crystal, left, compared with a two-dimensional glass, right. (b) The powder X-ray diffraction pattern of a glass (SiO2, orange) contrasted with that of a crystalline solid (quartz SiO2, blue). The long- range order, which gives rise to the sharp diffraction maxima in quartz, is no longer present in amorphous SiO2 and only broad features are seen.

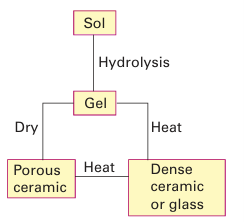

Figure 24.32 Comparison of the volume change for supercooled liquids and glasses with that for a crystalline material. The glass transition temperature is Tg. Another route to glasses is the sol–gel process, which is described schematically in Fig. 24.33 and discussed more fully in Section 25.4. As described there, the sol–gel process is also used to produce crystalline ceramic materials and high-surface-area compounds such as silica gel. A typical process involves the addition of a metal alkoxide precursor to an alcohol, followed by the addition of water to hydrolyse the reactants. This hydrolysis leads to a thick gel that can be dehydrated and sintered (heated below its melting point to Heat Dense ceramic or glass produce a compact solid). For example, ceramics containing TiO2 and Al2O3 can be pre pared in this way at much lower temperatures than required to produce the ceramic from the simple oxides. Often a special shape can be fashioned at the gel stage. Thus, the gel may be shaped into a fibre and then heated to expel water; this process produces a glass or ceramic fibre at much lower temperatures than would be necessary if the fibre were made from the melt of the components.

Figure 24.33 Schematic diagram of the sol–gel process. When the gel is dried at high temperatures dense ceramics or glasses are formed. Drying at low temperatures above the critical pressure of water produces porous solids known as xerogels or aerogels.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة