Rechargeable battery materials

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص622-623

الجزء والصفحة:

ص622-623

2025-10-11

2025-10-11

226

226

Rechargeable battery materials

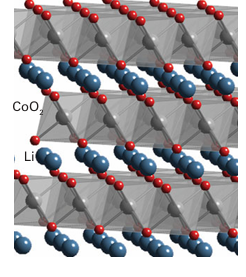

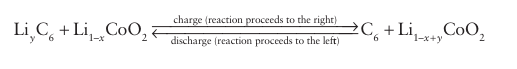

Key point: The redox chemistry associated with the extraction and insertion of metal ions into oxide structures is exploited in rechargeable batteries. The existence of complex oxide phases that demonstrate good ionic conductivity associated with the ability to vary the oxidation state of a d-metal ion has led to the development of materials for use as the cathode in rechargeable batteries (see Box 11.1). Examples in clude LiCoO2, with a layer-type structure based on sheets of edge-linked CoO6 octahedra separated by Li ions (Fig. 24.30), and various lithium manganese spinels, such as LiMn2O4. In each of these compounds the battery is charged by removing the mobile Li ions from the complex metal oxide, as in

The battery is discharged through the reverse electrochemical reaction. Lithium cobalt oxide, which is used in many commercial lithium-ion batteries, has many of the characteristics required for this type of application. The specific energy (the stored energy divided by the mass) of LiCoO2 (140 W h kg 1) is maximized by using light elements such as Li and Co; the 3d metals are almost invariably used in such applications because they are the lowest density elements with variable oxidation states. The high mobility of the Li ion and good reversibility of electrochemical charging and discharging stem from the lithium ion’s small ionic radius and the layer-like structure of LiCoO2, which allows the Li to be extracted without major disruption of the structure. High capacities are obtained from the large amount of Li (one Li ion for each LiCoO2 formula unit) that may be reversibly extracted (about 500 discharge/recharge cycles) from the compound, and the current is delivered at a constant and high potential difference (of between 3.5 and 4 V). The high potential difference is partly due to the high oxidation states of cobalt (+3 and+4) that are involved.

Because cobalt is expensive and fairly toxic, the search continues for even better oxide materials than LiCoO2 . New materials will be required to demonstrate the high levels of reversibility found for lithium cobaltite and considerable effort is being directed at doped forms of LiCoO2 and of LiMn2O4 spinels and at nanostructured complex oxides (Section 25.4), which, because of their small particle size, can offer excellent reversibility. There is also a high level of interest in LiFePO4, which shows good characteristics for a cathode material and contains cheap and nontoxic iron.

The other electrode in a rechargeable lithium-ion battery can simply be Li metal, which completes the overall cell reaction through the process Li(s) → Li+ +e-. Lithium ions then migrate to the cathode through an electrolyte, which is typically an anhydrous lithium salt, such as LiPF4 or LiC (SO2CF3)3 dissolved in a polymer, such as poly (propene carbonate).

Figure 24.30 The structure of LiCoO2 shown as layers of linked CoO6 octahedra separated by Li ions; lithium may be de-intercalated electrochemically from between the layers. However, the use of Li metal has a number of problems associated with its reactivity and volume changes that occur in the cell. Therefore, an alternative anode material that is frequently used in rechargeable batteries is graphitic carbon, which can intercalate, electro chemically, large quantities of Li to form LiC6 (Section 14.5). As the cell is discharged, Li is transferred from between the carbon layers at the anode and intercalated into the metal oxide at the cathode (and vice versa on charging) with the following overall processes:

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة