Atom and ion diffusion

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص606-607

الجزء والصفحة:

ص606-607

2025-10-08

2025-10-08

301

301

Atom and ion diffusion

Key point: The diffusion of ions in solids is strongly dependent on the presence of defects. One reason why diffusion in solids is much less familiar than diffusion in gases and liquids is that at room temperature it is generally very much slower. This slowness is why most solid-state reactions are undertaken at high temperatures (Section 24.1). However, there are some striking exceptions to this generalization. Diffusion of atoms or ions in solids is in fact very important in many areas of solid-state technology, such as semiconductor manufacture, the synthesis of new solids, fuel cells, sensors, metallurgy, and heterogeneous catalysis. The rates at which ions move through a solid can often be understood in terms of the mechanism for their migration and the activation barriers the ions encounter as they move. The lowest energy pathway generally involves defect sites with the roles summarized in Fig. 24.3. Materials that show high rates of diffusion at moderate temperatures have the following characteristics:

Low-energy barriers: so temperatures at (or a little above) 300 K are sufficient to permit ions to jump from site to site. Low charges and small radii: so, for example, the most mobile cation (other than the proton) and anion are Li+ and F-. Reasonable mobilities are also found for Na and O2. More highly charged ions develop stronger electrostatic interactions and are less mobile. High concentrations of intrinsic or extrinsic defects: defects typically provide a low energy pathway for diffusion through a structure that does not involve the energy penalties associated with continuously displacing ions from normal, favourable ion sites. These defects should not be ordered, as for crystallographic shear planes (Section 24.3), because such ordering removes the diffusion pathway. Mobile ions are present as a significant proportion of the total number of ions.

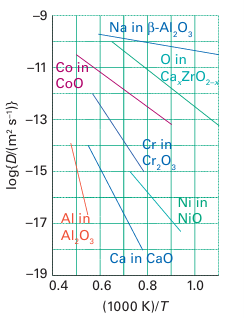

Figure 24.4 shows the temperature dependence of the diffusion coefficients, which are a measure of mobility, for specified ions in a selection of solids at high temperatures. The slopes of the lines are proportional to the activation energy for migration. Thus, Na is highly mobile and has a low activation energy for motion through -alumina, whereas Ca2 in CaO is much less mobile and has a high activation energy for hopping through the rock-salt structure.

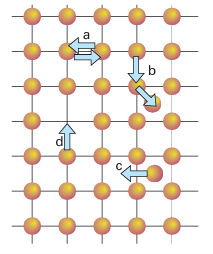

Figure 24.3 Some diffusion mechanisms for ions or atoms in a solid: (a) two atoms or ions exchange positions, (b) an ion hops from a normally occupied site in the structure to an interstitial site, which produces a vacancy which can then be filled by movement of an ion from another site, (c) an ion hops between two different interstitial sites and (d) an ion or atom moves from a normally occupied site to a vacancy, so producing a new vacant site.

As with the mechanisms of most chemical reactions, the evidence for the mechanism of a particular diffusion process is circumstantial. The individual events are never directly observed but are inferred from the influence of experimental conditions on diffusion rates. For example, a detailed analysis of the thermal motion and distributions of ions in crystals based on X-ray and neutron diffraction provides strong hints about the ability of ions to move through the crystal, including their most likely paths. Computer modelling, which is often an elaboration of the ionic model, also gives very useful guidance to the feasibility of these migration mechanisms.

Figure 24.4 The diffusion coefficients (on a logarithmic scale) as a function of inverse temperature for the mobile ion in selected solids.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة