Ligand substitution

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص568-570

الجزء والصفحة:

ص568-570

2025-10-06

2025-10-06

529

529

Ligand substitution

Key points: The substitution of ligands in organometallic complexes is very similar to the substitution of ligands in coordination complexes, with the additional constraint that the valence electron count at the metal atom does not increase above 18; steric crowding of ligands increases the rate of dissociative processes and decreases the rate of associative processes.

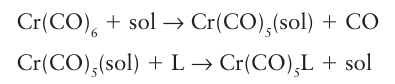

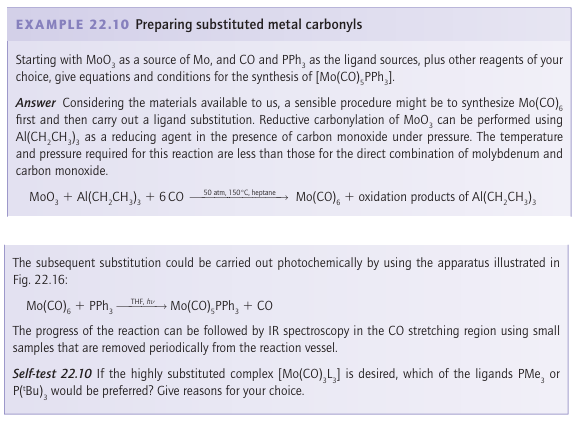

Extensive studies of CO substitution reactions of simple carbonyl complexes have revealed systematic trends in mechanisms and rates, and much that has been established for these compounds is applicable to all organometallic complexes. The simple replacement of one ligand by another in organometallic complexes is very similar to that observed with coordination compounds, where reactions sometimes go by an associative, a dissociative, or an interchange pathway, with the reaction being either associatively or dissociatively activated (Section 21.2). The simplest examples of substitution reactions involve the replacement of CO by another electron-pair donor, such as a phosphine. Studies of the rates at which trialkylphosphines and other ligands replace CO in Ni (CO)4, Fe (CO)5, and the hexacarbonyls of the chromium group show that they are relatively insensitive to the incoming group, indicating that a dissociatively activated mechanism is in operation. In some cases a solvated intermediate such as [Cr (CO)5(THF)] has been detected. This intermediate then combines with the entering group in a bimolecular process:

A dissociatively activated substitution reaction would be expected with metal carbonyl complexes as associative activation would require reaction intermediates with more than 18 valence electrons, formation of which corresponds to populating high-energy antibonding MOs.

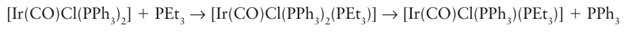

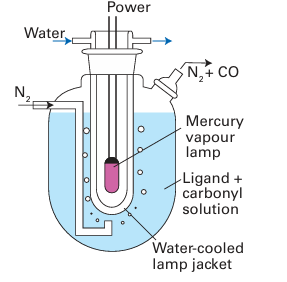

Whereas the loss of the first CO group from Ni(CO)4 occurs easily, and substitution is fast at room temperature, the CO ligands are much more tightly bound in the Group 6 carbonyls, and loss of CO often needs to be promoted thermally or photochemically. For example, the substitution of CO by CH3 CN is carried out in refluxing acetonitrile, using a stream of nitrogen to sweep away the carbon monoxide and hence drive the reaction to completion. To achieve photolysis, mononuclear carbonyls (which do not absorb strongly in the visible region) are exposed to near-UV radiation in an apparatus like that shown in Fig. 22.16. As with the thermal process, there is strong evidence that the photoassisted substitution reaction leads to the formation of a labile intermediate complex with the solvent, which is then displaced by the entering group. Solvated intermediates in the photolysis of metal carbonyls have been detected, not only in polar solvents such as THF but also in every solvent that has been tried, even in alkanes and noble gases.3 The rates of substitution of ligands in 16-electron complexes are sensitive to the identity and concentration of the entering group, which indicates associative activation. For exam ple, the reactions of [Ir (CO)Cl (PPh3)2] with triethyl phosphine are associatively activated:

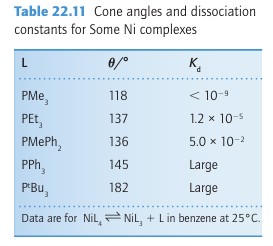

Sixteen-electron organometallic compounds appear to undergo associatively activated substitution reactions because the 18-electron activated complex is energetically more favour able than the 14-electron activated complex that would occur in dissociative activation. As in the reactions of coordination complexes, we can expect steric crowding between ligands to accelerate dissociative processes and to decrease the rates of associative processes (Section 21.6). The extent to which various ligands crowd each other is approximated by the Tolman cone angle and we can see how it influences the equilibrium constant for ligand binding by examining the dissociation constants of [Ni (PR3)4] complexes (Table 22.11). These complexes are slightly dissociated in solution if the phosphine ligands are compact, such as PMe3, with a cone angle of 118º. However, a complex such as [Ni (PtBu3)4], where the cone angle is huge (182º), is highly dissociated. The ligand PtBu3 is so bulky that the 14-electron complex [Pt (PtBu3)2] can be identified.

The rate of CO substitution in six-coordinate metal carbonyls often decreases as more strongly basic ligands replace CO, and two or three alkylphosphine ligands often represent the limit of substitution. With bulky phosphine ligands, further substitution may be ther modynamically unfavourable on account of ligand crowding, but increased electron density on the metal centre, which arises when a π-acceptor ligand is replaced by a net donor ligand, appears to bind the remaining CO ligands more tightly and therefore reduce the rate of CO dissociative substitution. The explanation of the influence of -donor ligands on CO bonding is that the increased electron density contributed by the phosphine leads to stronger π backbonding to the remaining CO ligands and therefore strengthens the MCO bond. This stronger MC bond decreases the tendency of CO to leave the metal atom and therefore decreases the rate of dissociative substitution. It is also observed that the second carbonyl that is replaced is normally cis to the site of the first and that replace ment of a third carbonyl results in a fac complex. The reason for this regiochemistry is that CO ligands have very high trans effects (Section 21.4).

Figure 22.16 Apparatus for photochemical ligand substitution of metal carbonyls.

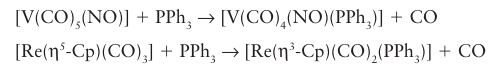

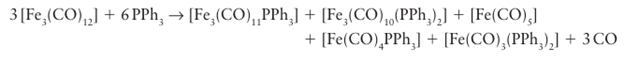

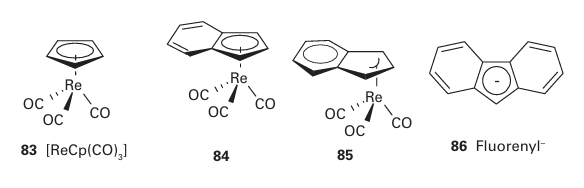

Although the generalizations above apply to a wide range of reactions, some exceptions are observed, especially if cyclopentadienyl or nitrosyl ligands are present. In these cases it is common to find evidence of associatively activated substitution even for 18-electron complexes. The common explanation is that NO may switch from being linear (as in 67) to being angular (as in 68), whereupon it donates two fewer electrons (Section 22.17). Similarly, the 5-Cp six-electron donor can slip relative to the metal and become an 3-Cp four-electron donor. In this case, the C5H5- ligand is regarded as having a three-carbon interaction with the metal while the remaining two electrons form a simple C=C bond that is not engaged with the metal (82), and the relatively electron-depleted central metal atom becomes susceptible to substitution:

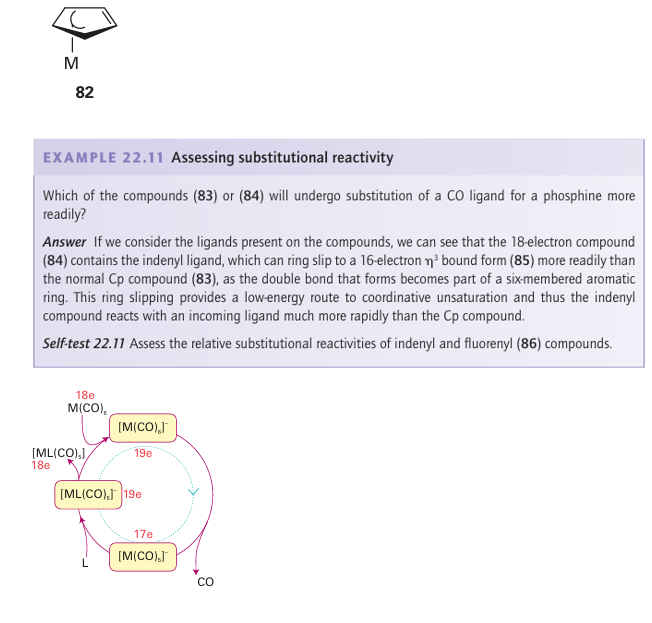

It has been found that, for some metal carbonyls, the displacement of CO can be catalysed by electron-transfer processes that create anion or cation radicals. These radicals do not have 18 electrons, and a typical process of this type is illustrated in Fig. 22.17. As can be seen, the key feature is the lability of CO in the 19-electron anion radical compared to the metal carbonyl starting material. Similarly, the less common 19- and 17-electron metal compounds are labile with respect to substitution. The substitution of ligands at a cluster is often not a straightforward process because fragmentation is common. Fragmentation occurs because the MM bonds in a cluster are generally comparable in strength to the M L bonds, and so the breaking of the MM bonds provides a reaction pathway with a low activation energy. For example, dodecacarbonyltriiron (0) reacts with triphenylphosphine under mild conditions to yield simple mono- and disubstituted products as well as some cluster fragmentation products:

However, for somewhat longer reaction times or elevated temperatures, only monoiron cleavage products are obtained. Because the strength of MM bonds increases down a group, substitution products of the heavier clusters, such as [Ru3 (CO)10 (PPh3)2] or [Os3 (CO)10(PPh3)2], can be prepared without significant fragmentation into mononuclear complexes.

Figure 22.17 Schematic diagram of an electron transfer catalysed CO substitution. After addition of a small amount of a reducing initiator, the cycle continues until the limiting reagent M(CO)6 or L has been consumed.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة