Hydrides and dihydrogen complexes

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص543-544

الجزء والصفحة:

ص543-544

2025-10-01

2025-10-01

306

306

Hydrides and dihydrogen complexes

Key points: The bonding of a hydrogen atom to a metal atom is a σ interaction, whereas the bonding of a dihydrogen ligand involves π backbonding. A hydrogen atom directly bonded to a metal is commonly found in organometallic complexes and is referred to as a hydride ligand. The name ‘hydride’ can be misleading as it implies a H ligand. Although the formulation H might be appropriate for most hydrides, such as [CoH (PMe3)4], some hydrides are appreciably acidic and behave as though they contain H, for example [CoH (CO)4] is an acid with pKa= 8.3 (in acetonitrile). The acid ity of organometallic carbonyls is described in Section 22.18. In the donor-pair method of electron counting, we consider the hydride ligand to contribute two electrons and to have a single negative charge (that is, to be H). The bonding of a hydrogen atom to a metal atom is simple because the only orbital of appropriate energy for bonding on the hydrogen is H1s and the MH bond can be con sidered as a σ interaction between the two atoms. Hydrides are readily identified by NMR spectroscopy as their chemical shift is rather unusual, typically occurring in the range 50<Ϭ<0.

Infrared spectroscopy can also be useful in identifying metal hydrides as they normally have a stretching band in the range 2850 2250 cm1. X-ray diffraction, normally so valuable for identifying the structure of crystalline materials, is of little use in identify ing hydrides because the diffraction is related to electron density, and the hydride ligand will have at most two electrons around it, compared with, for instance, 78 for a platinum.

Neutron diffraction is of more use in locating hydride ligands, especially if the hydrogen atom is replaced by a deuterium atom, because deuterium has a large neutron scattering cross-section. An MH bond can sometimes be produced by protonation of an organometallic com pound, such as neutral and anionic metal carbonyls (Section 22.18e). For example, ferrocene can be protonated in strong acid to produce an Fe H bond:

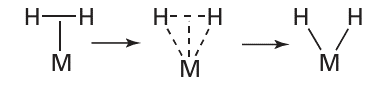

Bridging hydrides exist, where an H atom bridges either two or three metal atoms: here the bonding can be treated in exactly the same way we considered bridging hydrides in diborane, B2H6 (Section 2.11). Although the first organometallic metal hydride was reported in 1931, complexes of hydrogen gas, H2 , were identified only in 1984. In such compounds, the dihydrogen molecule, H2 , bonds side-on to the metal atom (in the older literature, such compounds were sometimes called non-classical hydrides). The bonding of dihydrogen to the metal atom is considered to be made up of two components: a σ donation of the two electrons in the H2 bond to the metal atom (24) and a π backdonation from the metal to the σ* antibonding orbital of H2 (25). This picture of the bonding raises a number of interesting issues. In particular, as the π backbonding from the metal atom increases, the strength of the HH bond decreases and the structure tends to that of a dihydride:

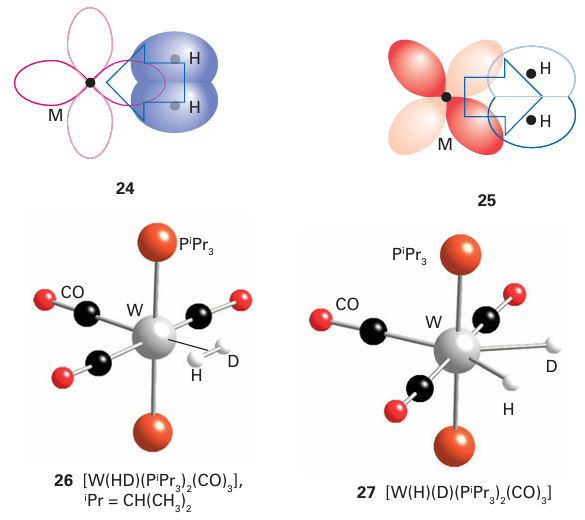

A dihydrogen molecule is treated as a neutral two-electron donor. Thus, the transformation of the dihydrogen into two hydrides (each considered to have a single negative charge and to contribute two electrons) requires the formal charge on the metal atom to increase by two. That is, the metal is oxidized by two units and the dihydrogen is reduced. Although it might seem that this oxidation of the metal is just an anomaly thrown up by our method of counting electrons, two of the electrons on the metal atom have been used to back bond to the dihydrogen, and these two electrons are no longer available to the metal atom for fur ther bonding. This transformation of the dihydrogen molecule to a dihydride is an exam ple of oxidative addition, and is discussed more fully later in this chapter (Section 22.22). It is now recognized that complexes exist with structures at all points between these two extremes, and in some cases an equilibrium can be identified between the two. Work by G. Kubas on tungsten complexes used the H D coupling constant to show that it is possible to detect both the dihydrogen complex (26, 1JHD=34Hz) and the dihydride (27, 2JHD<2Hz), and to follow the conversion from one to the other. Certain microbes contain enzymes known as hydrogenases that use Fe and Ni at their catalytic centres to catalyse the rapid oxidation of H2 and reduction of H, via intermediate metal dihydrogen and hydride species (Section 27.14).

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة