Carbon monoxide

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص540-542

الجزء والصفحة:

ص540-542

2025-09-30

2025-09-30

416

416

Carbon monoxide

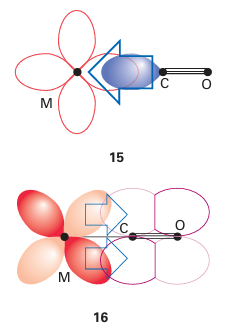

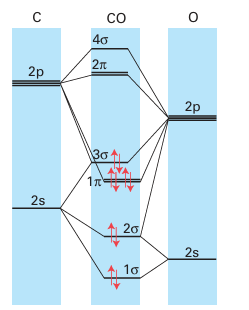

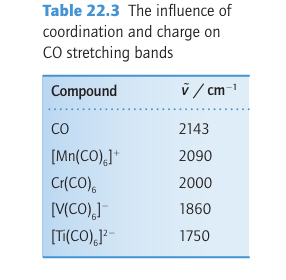

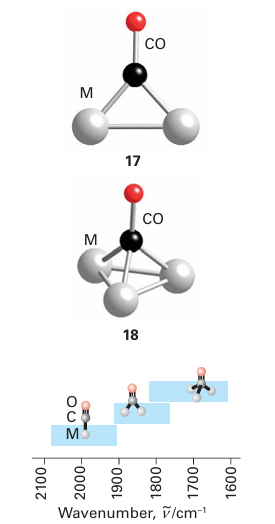

Key point: The 3Ϭ orbital of CO serves as a very weak donor and the π* orbitals act as acceptors. Carbon monoxide is a very common ligand in organometallic chemistry, where it is known as the carbonyl group. Carbon monoxide is particularly good at stabilizing very low oxidation states, with many compounds (such as Fe (CO)5) having the metal in its zero-oxidation state. We described the molecular orbital structure of CO in Section 2.9, and it would be sensible to review that section. A simple picture of the bonding of CO to a metal atom is to treat the lone pair on the carbon atom as a Lewis σ base (an electron-pair donor) and the empty CO antibonding orbital as a Lewis π acid (an electron-pair acceptor), which accepts π-electron density from the filled d orbitals on the metal atom. In this picture, the bonding can be considered to be made up of two parts: a σ bond from the ligand to the metal atom (15) and a π bond from the metal atom to the ligand (16). This type of π bonding is sometimes referred to as backbonding. Carbon monoxide is not appreciably nucleophilic, which suggests that σ bonding to a d-metal atom is weak. As many d-metal carbonyl compounds are very stable, we can also infer that π backbonding is strong and the stability of carbonyl complexes arises mainly from the π-acceptor properties of CO. Further evidence for this view comes from the observation that stable carbonyl complexes exist only for metals that have filled d orbitals of an energy suitable for donation to the CO antibonding orbital. For instance, elements in the s and p blocks do not form stable carbonyl complexes. However, the bonding of CO to a d metal atom is best regarded as a synergistic (that is, mutually enhancing) out-come of both σ and π bonding: the π backbonding from the metal to the CO increases the electron density on the CO, which in turn increases the ability of the CO to form a σ bond to the metal atom. A more formal description of the bonding can be derived from the molecular orbital scheme for CO (Fig. 22.3), which shows that the HOMO has σ symmetry and is essentially a lobe that projects away from the C atom. When CO acts as a ligand, this 3σ or bital serves as a very weak donor to a metal atom, and forms a σ bond with the central metal atom. The LUMOs of CO are the π* orbitals. These two orbitals play a crucial role because they can overlap with metal d orbitals that have local π symmetry (such as the t2g orbitals in an Oh complex). The π interaction leads to the delocalization of electrons from filled d orbitals on the metal atom into the empty π* orbitals on the CO ligands, so the ligand also acts as a π acceptor. One important consequence of this bonding scheme is the effect on the strength of the CO triple bond: the stronger the metal carbon bond becomes through pushing electron density from the metal atom into the π bond, the weaker the CO bond becomes, as this electron density enters a CO antibonding orbital. In the extreme case, when two electrons are fully donated by the metal atom, a formal metal carbon double bond is formed; because the two electrons occupy a CO antibonding orbital, this donation results in a decrease in the bond order of the CO to 2. In practice, the bonding is somewhere between MC O, with no backbonding, and MC O, with complete backbonding. Infrared spectroscopy is a very convenient method of assessing the extent of π bonding; the CO stretch is clearly identifiable as it is both strong and normally clear of all other absorptions. In CO gas, the absorption for the triple bond is at 2143 cm1, whereas a typical metal carbonyl complex has a stretching mode in the range 2100 1700 cm1 (Table 22.3). The number of IR absorptions that occur in a particular carbonyl compound is discussed in Section 22.18g. Carbonyl stretching frequencies are often used to determine the order of acceptor or donor strengths for the other ligands present in a complex. The basis of the approach is that the CO stretching frequency is decreased when it serves as a π acceptor. However, as other π acceptors in the same complex compete for the d electrons of the metal atom, they cause the CO frequency to increase. This behaviour is opposite to that observed with donor ligands, which cause the CO stretching frequency to decrease as they supply electrons to the metal atom and hence, indirectly, to the CO π* orbitals. Thus, strong σ-donor ligands attached to a metal carbonyl and a formal negative charge on a metal carbonyl anion both result in slightly greater CO bond lengths and significantly lower CO stretching frequencies. Carbon monoxide is versatile as a ligand because, as well as the bonding mode we have described so far (often referred to as ‘terminal’), it can bridge two (17) or three (18) metal atoms. Although the description of the bonding is now more complicated, the concepts of σ-donor and π-acceptor ligands remain useful. The CO stretching frequencies generally follow the order MCO M2 CO M3 CO, which suggests an increasing occupation of the π* orbital as the CO molecule bonds to more metal atoms and more electron density from the metals enters the CO π* orbitals. As a rule of thumb, carbonyls bridging two metal atoms typically have stretching bands in the range 1900 1750 cm1, and those that bridge three atoms have stretching bands in the range 1800 1600 cm1 (Fig. 22.4). We consider carbon monoxide to be a two-electron neutral ligand when terminal or bridging (thus a carbonyl bridging two metals can be considered to give one electron to each). A further bonding mode for CO that is sometimes observed is when the CO is terminally bound to one metal atom and the CO triple bond binds side-on to another metal (19). This description is best considered as two separate bonding interactions, with the terminal interaction being the same as that described above and the side-on bonding being essentially identical to that of other side-on π donors such as alkynes and N2, which are discussed later. The synthesis, properties, and reactivities of compounds containing the carbonyl ligand are discussed in more detail in Section 22.18.

Figure 22.3 The molecular orbital scheme for CO shows that the HOMO has σ symmetry and is essentially a lobe that projects away from the C atom. The LUMO has π symmetry.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة