Rates of ligand substitution

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص507-509

الجزء والصفحة:

ص507-509

2025-09-29

2025-09-29

349

349

Rates of ligand substitution

Key points: The rates of substitution reactions span a very wide range and correlate with the structures of the complexes; complexes that react quickly are called labile, those that react slowly are called inert or nonlabile.

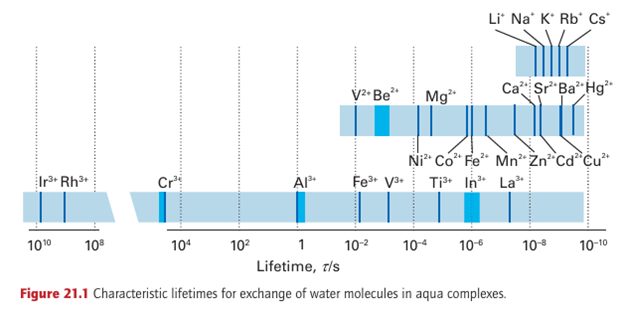

Rates of reaction are as important as equilibria in coordination chemistry. The numerous isomers of the ammines of Co (III) and Pt (II), which were so important to the development of the subject, could not have been isolated if ligand substitutions and interconversion of the isomers had been fast. But what determines whether one complex will survive for long periods whereas another will undergo rapid reaction? The rate at which one complex converts into another is governed by the height of the activation energy barrier that lies between them. Thermodynamically unstable complexes that survive for long periods (by convention, at least a minute) are commonly called ‘inert’, but nonlabile is more appropriate and is the term we shall use. Complexes that undergo more rapid equilibration are called labile. An example of each type is the labile complex [Ni (OH2)6]2+, which has a half-life of the order of milliseconds before the H2O is replaced by another H2 O or a stronger base, and the nonlabile complex [Co (NH3)5 (OH2)]3, in which H2O survives for several minutes as a ligand before it is replaced by a stronger base. Figure 21.1 shows the characteristic lifetimes of the important aqua metal ion complexes. We see a range of lifetimes starting at about 1 ns, which is approximately the time it takes for a molecule to diffuse one molecular diameter in solution. At the other end of the scale are lifetimes in years. Even so, the illustration does not show the longest times that could be considered, which are comparable to geological eras. We shall examine the lability of complexes in greater detail when we discuss the mechanism of reactions later in this section, but we can make two broad generalizations now. The first is that complexes of metals that have no additional factor to provide extra stability (for instance, the LFSE and chelate effects) are among the most labile. Any additional stability of a complex results in an increase in activation energy for a ligand replacement reaction and hence decreases the lability of the complex. A second generalization is that very small ions are often less labile because they have greater M L bond strengths and it is sterically very difficult for incoming ligands to approach the metal atom closely. Some further generalizations are as follows:

1. All complexes of s-block ions except the smallest (Be2 and Mg2) are very labile.

2. Complexes of the M(III) ions of the f block are all very labile.

3. Complexes of the d10 ions (Zn2, Cd2, and Hg2) are normally very labile.

4. Across the 3d series, complexes of d-block M(II) ions are generally moderately labile, with distorted Cu (II) complexes among the most labile.

5. Complexes of d-block M(III) ions are distinctly less labile than d-block M(II) ions.

6. d-Metal complexes with d3 and low-spin d6 configurations (for example Cr (III), Fe (II), and Co (III)) are generally nonlabile as they have large LFSEs. Chelate complexes with the same configuration, such as [Fe(phen)3 ]2, are particularly inert.

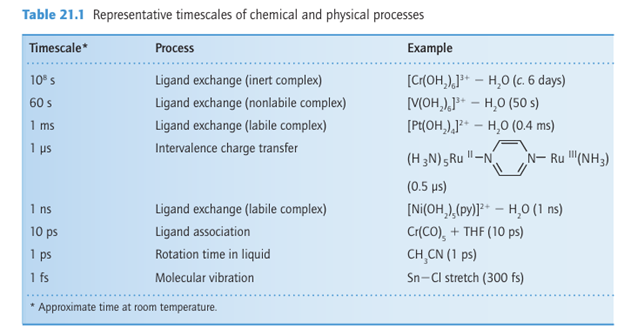

7. Nonliability is common among the complexes of the 4d and 5d series, which reflects the high LFSE and strength of the metal ligand bonding. Table 21.1 illustrates the range of timescales for a number of reactions. The natures of the ligands in the complex also affect the rates of reactions. The identity of the incoming ligand has the greatest effect, and equilibrium constants of displacement reactions can be used to rank ligands in order of their strength as Lewis bases. However, a different order may be found if bases are ranked according to the rates at which they displace a ligand from the central metal ion. Therefore, for kinetic considerations, we replace the equilibrium concept of basicity by the kinetic concept of nucleophilicity, the rate of attack on a complex by a given Lewis base relative to the rate of attack by a reference Lewis base. The shift from equilibrium to kinetic considerations is emphasized by referring to ligand displacement as nucleophilic substitution. Ligands other than the entering and leaving groups may play a significant role in controlling the rates of reactions; these ligands are referred to as spectator ligands.

For instance, it is observed for square-planar complexes that the ligand trans to the leaving group X has a great effect on the rate of substitution of X by the entering group Y.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة