π Bonding

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص486-487

الجزء والصفحة:

ص486-487

2025-09-28

2025-09-28

336

336

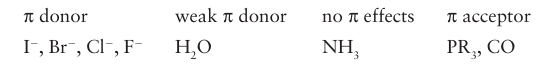

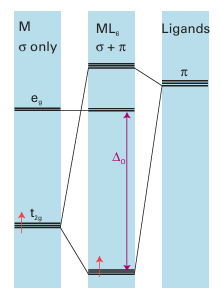

π Bonding

Key points: π-Donor ligands decrease ΔO whereas π-acceptor ligands increase ΔO; the spectrochemical series is largely a consequence of the effects of π bonding when such bonding is feasible. If the ligands in a complex have orbitals with local π symmetry with respect to the M L axis (as two of the p orbitals of a halide ligand have), they may form bonding and anti- bonding π orbitals with the metal orbitals (Fig. 20.19). For an octahedral complex the combinations that can be formed from the ligand π orbitals include SALCs of t2g symmetry. These ligand combinations have net overlap with the metal t2g orbitals, which are therefore no longer purely nonbonding on the metal atom. Depending on the relative energies of the ligand and metal orbitals, the energies of the now molecular t2g orbitals lie above or below the energies they had as nonbonding atomic orbitals, so ∆O is decreased or increased, respectively. To explore the role of π bonding in more detail, we need two of the general principles. First, we shall make use of the idea that, when atomic orbitals overlap strongly, they mix strongly: the resulting bonding molecular orbitals are significantly lower in energy and the antibonding molecular orbitals are significantly higher in energy than the atomic orbitals. Second, we note that atomic orbitals with similar energies interact strongly, whereas those of very different energies mix only slightly even if their overlap is large. Aπ-donor ligand is a ligand that, before any bonding is considered, has filled orbitals of π symmetry around the M L axis. Such ligands include Cl, Br, OH, O2 and even H2O. In Lewis acid base terminology (Section 4.9), a π-donor ligand is a π base. The energies of the full π orbitals on the ligands will not normally be higher than their -donor orbitals (HOMO) and must therefore also be lower in energy than the metal d orbitals. Because the full π orbitals of π donor ligands lie lower in energy than the partially filled d orbitals of the metal, when they form molecular orbitals with the metal t2g orbitals, the bonding com bination lies lower than the ligand orbitals and the antibonding combination lies above the energy of the d orbitals of the free metal atom (Fig. 20.20). The electrons supplied by the ligand π orbitals occupy and fill the bonding combinations, leaving the electrons originally in the d orbitals of the central metal atom to occupy the antibonding t2g orbitals. The net effect is that the previously nonbonding metal t2g orbitals become antibonding and hence are raised closer in energy to the antibonding eg orbitals. It follows that π-donor ligands decrease ΔO. A π-acceptor ligand is a ligand that has empty π orbitals that are available for occupation. In Lewis acid base terminology, a π-acceptor ligand is a π acid. Typically, the π-acceptor orbitals are vacant antibonding orbitals on the ligand (usually the LUMO), as in CO and N2, which are higher in energy than the metal d orbitals. The two π* orbit als of CO, for instance, have their largest amplitude on the C atom and have the correct symmetry for overlap with the metal t2g orbitals, so CO can act as a π-acceptor ligand

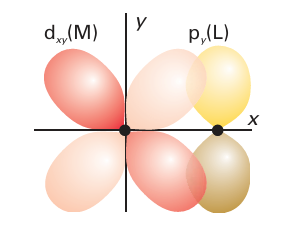

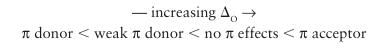

Figure 20.19 The π overlap that may occur between a ligand p orbital perpendicular to the M-L axis and a metal dxy orbital. (Section 22.5). Phosphines (PR3) are also able to accept π-electron density and also act as π acceptors (Section 22.6). Because the π-acceptor orbitals on most ligands are higher in energy than the metal d orbitals, they form molecular orbitals in which the bonding t2g combinations are largely of metal d-orbital character (Fig. 20.21). These bonding combinations lie lower in energy than the d orbitals themselves. The net result is that π-acceptors increase ∆O. We can now put the role of π bonding in perspective. The order of ligands in the spectrochemical series is partly that of the strengths with which they can participate in M-L Ϭ bonding. For example, both CH3- and H- are very high in the spectrochemical series because they are very strong Ϭ donors. However, when π bonding is significant, it has a strong influence on ∆O: π-donor ligands decrease ∆O and π-acceptor ligands increase ∆O. This effect is responsible for CO (a strong π acceptor) being high on the spectrochemical series and for OH- (a strong π donor) being low in the series. The overall order of the spectrochemical series may be interpreted in broad terms as dominated by π effects (with a few important exceptions), and in general the series can be interpreted as follows:

Representative ligands that match these classes are

Notable examples of where the effect of bonding dominates include amines (NR3), CH3-, and H, none of which has orbitals of π symmetry of an appropriate energy and thus are neither π-donor nor π-acceptor ligands. It is important to note that the classification of a ligand as strong-field or weak-field does not give any guide as to the strength of the M—L bond.

Figure 20.20 The effect of π bonding on the ligand-field splitting parameter. Ligands that act as π donors decrease ∆O. Only the π orbitals of the ligand are shown.

Figure 20.21 Ligands that act as π acceptors increase ∆O. Only the π orbitals of the ligand are shown.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة