The inner-sphere mechanism

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص524-527

الجزء والصفحة:

ص524-527

2025-09-27

2025-09-27

343

343

The inner-sphere mechanism

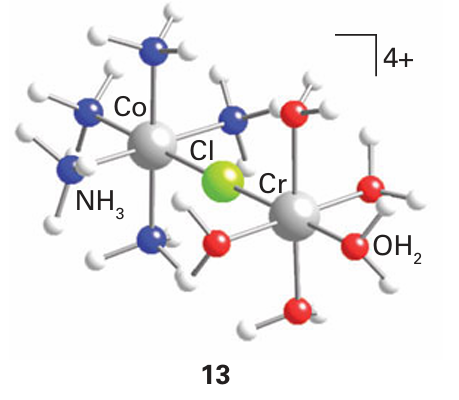

Key point: The rate-determining step of an inner-sphere redox reaction may be any one of the component processes, but a common one is electron transfer. The inner-sphere mechanism was first confirmed for the reduction of the nonlabile com plex [CoCl (NH3)5]+2 by Cr2 (aq). The products of the reaction included both Co2 (aq) and [CrCl (OH2)5]+2, and addition of 36Cl to the solution did not lead to the incorporation of any of the isotope into the Cr (III) product. Furthermore, the reaction is much faster than reactions that remove Cl from nonlabile Co (III) or introduce Cl into the nonlabile [Cr (OH2)6]+3 complex. These observations suggest that Cl has moved directly from the coordination sphere of one complex to that of the other during the reaction. The Cl attached to Co(III) can easily enter into the labile coordination sphere of [Cr (OH2)6]+2 to produce a bridged intermediate (13). Inner-sphere reactions, though involving more steps than outer-sphere reactions, can be fast. Figure 21.16 summarizes the steps necessary for such a reaction to occur.

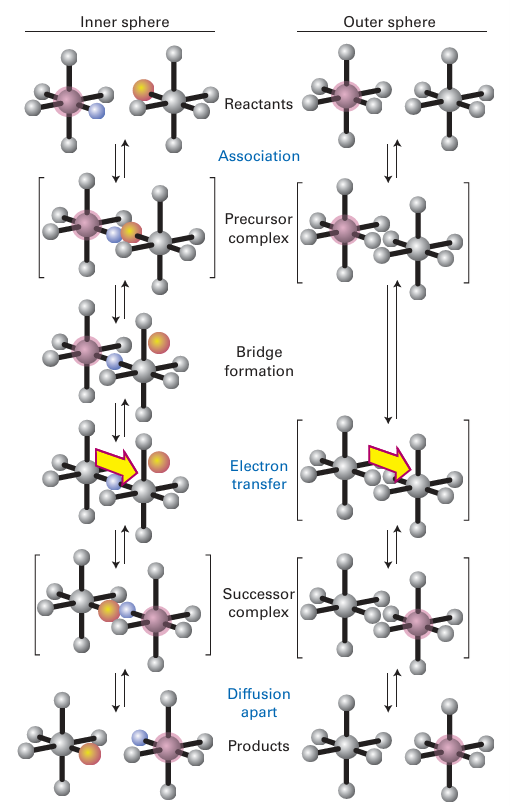

Figure 21.16 The different pathways followed by inner- and outer-sphere mechanisms.

The first two steps of an inner-sphere reaction are the formation of a precursor complex and the formation of the bridged binuclear intermediate. These two steps are identical to the first two steps in the Eigen Wilkins mechanism (Section 21.5). The final steps are electron transfer through the bridging ligand to give the successor complex, followed by dissociation to give the products. The rate-determining step of the overall reaction may be any one of these processes, but the most common one is the electron-transfer step. However, if both metal ions have a nonlabile electron configuration after electron transfer, then the break-up of the bridged complex is rate determining. An example is the reduction of [RuCl(NH3)5]+2

by [Cr (OH2 )6 ]2, in which the rate-determining step is the dissociation of the Cl-bridged complex [RuII (NH3)5 (μ-Cl) CrIII (OH2)5]4+. Reactions in which the formation of the bridged complex is rate determining tend to have similar rate constants for a series of partners of a given species. For example, the oxidation of V2 (aq) has similar rate constants for a long series of Co (III) oxidants with different bridging ligands. The explanation is that the rate determining step is the substitution of an H2 O molecule from the coordination sphere of V(II), which is quite slow (Table 21.8).

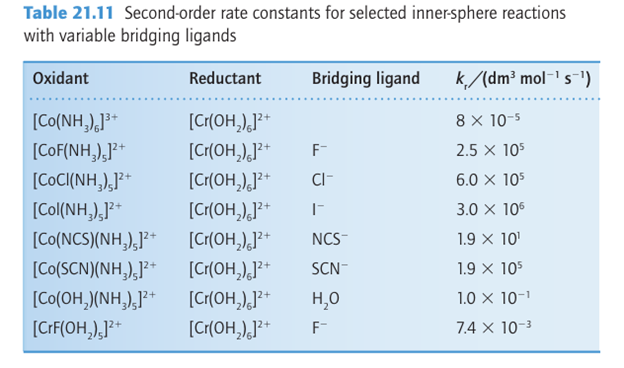

The numerous reactions in which electron transfer is rate determining do not display such simple regularities. Rates vary over a wide range as metal ions and bridging ligands are varied.4 The data in Table 21.11 show some typical variations as bridging ligand, oxidizing metal, and reducing metal are changed. All the reactions in Table 21.11 result in the change of oxidation number by ±1. Such reactions are still often called one-equivalent processes, the name reflecting the largely outmoded term ‘chemical equivalent’. Similarly, reactions that result in the change of oxdation number by ±2 are often called two-equivalent processes and may resemble nucleophilic substitutions. This resemblance can be seen by considering the reaction

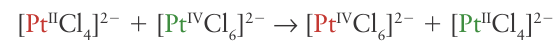

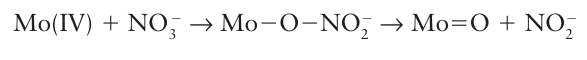

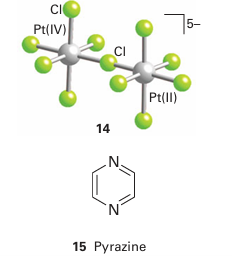

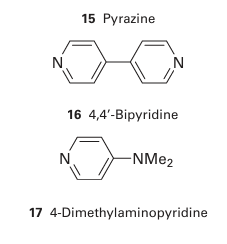

which occurs through a Cl bridge (14). The reaction depends on the transfer of a Cl-ion in the break-up of the successor complex. There is no difficulty in assigning an inner-sphere mechanism when the reaction involves ligand transfer from an initially nonlabile reactant to a nonlabile product. With more labile complexes, inner-sphere reactions should always be suspected when ligand transfer occurs as well as electron transfer, and if good bridging groups such as Cl-, Br-, I-, N3-, CN-, SCN-, pyrazine (15), 4,4-bipyridine (16), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (17) are present. Although all these ligands have lone pairs to form the bridge, this may not be an essential requirement. For instance, just as the carbon atom of a methyl group can act as a bridge between OH and I in the hydrolysis of iodomethane, so it can act as a bridge between Cr (II) and Co (III) in the reduction of methyl cobalt species by Cr (II). The oxidation of a metal centre by oxidoanions is also an example of an inner-sphere process. For example, in the oxidation of Mo (IV) by NO3 ions, an O atom of the nitrate ion binds to the Mo atom, facilitating the electron transfer from Mo to N, and then remains bound to the Mo (VI) product:

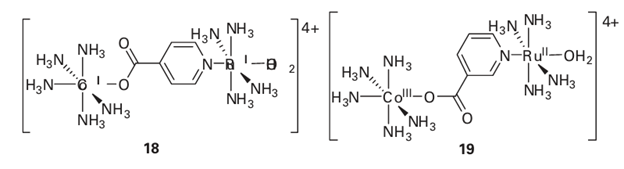

A brief illustration. Therate constant for the oxidation of the Ru (II) centre by the Co (III) centre in the bimetallic complex (18) is 1.0 102 dm3 mol 1 s 1, whereas the rate constant for complex (19) is 1.6 10 2 dm3 mol 1 s 1. In both complexes there is a pyridine carboxylic acid group bridging the two metal centres. These groups are bound to both metal atoms and could facilitate an

4Somebridged intermediates have been isolated with the electron clearly located on the bridge, but we shall not consider these here. electron-transfer process through the bridge, suggesting an inner-sphere process. The fact that the rate constant changes between the two complexes, when the only substantive difference between them is in the substitution pattern of the pyridine ring, confirms that the bridge must be playing a role in the electron transfer process.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة