Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The role of back-formation

المؤلف:

Ingo Plag

المصدر:

Morphological Productivity

الجزء والصفحة:

P206-C7

2025-02-11

1074

The role of back-formation

The most common of these processes is back-formation, which I take to be "the formation of a new lexeme by the deletion of a suffix, or supposed suffix, from an apparently complex form by analogy with other instances where the suffixed and non-suffixed forms are both lexemes" (Bauer 1983:64). The decision whether a form is a back-formation or not is sometimes both theoretically and empirically controversial, but I will adduce three kinds of evidence to substantiate my analysis, namely the dates of the earliest attestations as given in the OED, the close semantic relationship between model form and back-formed verb, and the aberrant phonological properties of some of the back-formed verbs.

Of the 72 verbs in the corpus, 38 are first attested at least one year later than the complex noun from which they are presumably back-formed, and 18 are first attested in the same year, of which 12 are first attested in the same text as the related noun. These facts clearly indicate that a huge portion of -ate verbs, if not the majority, do not arise through the suffixation of -ate to a given base, but through back-formation from nomina actionis in -ation.1 The reason for the high number of back-formations is rather obvious: the existence of the suffix -ation on the one hand, and the fact that all -ate verbs can be nominalized by the attachment of -ion on the other. Thus every noun in -ation is a possible candidate for the back-formation of a verb in -ate.

Although -ation has often been analyzed as a combination of -ate and -ion, both older and newer pairs like declare-declaration (noun first attested 1340) derive-derivation (noun: 1530), starve-starvation (noun: 1778) show that -ation also exists as a non-compositional suffix, since there are no corresponding forms ?declarate, ?derivate, ?starvate.2 The neologisms and their related forms as given in the OED suggest that this non-compositional suffix is especially productive in the realm of chemical-technical terminology and primarily attaches to nouns (e.g. epoxide - epoxidation). This analysis of -ation runs counter to standard sources, which treat -ation as an exclusively deverbal suffix. The data indicate, however, that this cannot be the whole story and even Marchand states that "[substantives in -ation which go with verbs in -ate are, as a rule, older than the verbs." (1969:260). In view of these facts the most natural conclusion - not drawn by Marchand, however - would be to analyze most of these -ate verbs as back-formations.

There is, however, also the possibility that most of the putative -ation nouns are in fact nominalizations not of actual but of possible -ate verbs. The above-cited epoxidation (first attested 1945) would be a case in point, since !epoxidate, though not attested, is certainly a possible form. This escape hatch has in fact been used by Marchand to account for the existence of sedimentation, for which no verbal -ate base is attested. He submits that, for example, in the case of sedimentation, "-ation derives a noun from a verb that exists only virtually" (1969:261). Under this assumption the lack of an attested base verb for a given -ation noun is pragmatically conditioned, it is simply not needed. This type of approach would have wider implications also for the semantic analysis of -ate. Assuming that -ation nouns are all derived from possible -ate verbs, the meaning of a semantically transparent -ation noun would depend on the meaning of its base, i.e. the possible -ate verb. Given the heterogeneous meaning of -ation derivatives, we would have to assume that -ate is just as indeterminate in meaning as the action nomináis putatively derived from it. Consequently, the LCS proposed above would be wrong, and the meaning of -ate would be as indeterminate as that of -ation, i.e. simply denoting an Event having to do with what is denoted by the base. Such an analysis will be proposed for denominal zero-derived verbs below, but, as we will see, it is not feasible for all -ate formations.

The decision for a very general verbal meaning (as against the LCS above) would hinge, among other things, on the acceptance of the claim that the -ation nouns are derived from possible but unattested -ate verbs. This claim is, however, most problematic. First, the existence of forms like derivation, declaration, perseveration, starvation, etc. clearly shows that -ation has an independent status as a non-compositional suffix. Second, as pointed out by Rainer (1993:99), the postulation of one compound suffix instead of two stacked ones is all the more plausible, the more often the compound suffix is attested without a corresponding single affix form. As conceded by Marchand, it is the rule rather than the exception, that the -ation form is attested earlier than the -ate form, and the same holds for the neologisms in our corpus. These facts are strong evidence against the successive suffixation of -ate and -ion in the cases under discussion.

Another major argument for the back-formation analysis is the close semantic relationship between model noun and back-formed verb. In general, the meaning dependency between a putatively back-formed word and its model is crucial evidence for a back-formation (see e.g. the discussion in Becker 1993a, 1993b). We would therefore predict that the indeterminacy of the meaning of -ation derivatives is reflected in the meaning of back-derived verbs. Under this approach, the heterogeneity of the -ate verbs turns out to be the direct consequence of their derivational history.

A full-fledged analysis of the semantic properties of -ation derivatives is beyond the scope of the present investigation, but as already mentioned above, the data suggest that action nominals in -ation merely denote an Event having to do with the entity denoted by the base. The postulation of a more specific meaning seems not to be justified in view of the semantic variation among the forms. On the basis of the meaning of -ation just proposed it can be (correctly) predicted that, for example, cavitation denotes an Event in which a cavity or cavities are involved in some manner. The lexicalized meaning 'The formation of bubbles or cavities in a fluid, esp. by the rapid motion of a propeller’ (OED) is certainly more specific, but conforms to the general semantics of -ation. The semantics of the back-formed verbs directly reflect the semantics of the action nominal from which they are derived. This close relationship between verb and action nominal is especially striking in those cases where more idiosyncratic meanings are involved, but a parallel analysis applies to the less idiosyncratic cases.

Let us consider, for example, escalate, formate and perseverate. The verb escalate can have two meanings, each of which is derived from their respective model word. The first meaning, that of escalate1, can be paraphrased as 'To climb or reach by means of an escalator ... To travel on an escalator' (OED), and is thus closely related to escalator. The second meaning, associated with esacalate2, is roughly synonymous with 'increase in intensity', which is derived from escalation.3 The second example, formate, is obviously coined in analogy to formation, as it is clearly indicated by the OED's paraphrase 'Of an aircraft or its pilot: to take up formation with, to fly in formation'. Finally, the meaning of perseverate, a technical term used in psychology, is given by the OED as 'To repeat a response after the cessation of the original stimulus, in various senses of perseveration2'. Perseveration is paraphrased in the OED as 'The tendency for an activity to be persevered with or repeated after the cessation of the stimulus to which it originally responded'. In all of these examples the -ate verb is semantically dependent on the action noun, and the noun is also attested a number of years earlier than the verb.

The final argument for the back-formation analysis comes from phonological facts. As already mentioned above, there are a number of verbs that have prosodic patterns that do not conform to the regular one of -ate verbs. Of these, the following are attested in the same year or later than the corresponding action nominals in -ation:4

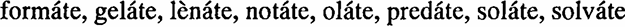

(1)

The derivatives in (1) all have primary stress on the last syllable. The aberrant phonological behavior of these forms is however naturally accounted for if we assume that they simply have preserved the stress pattern of their model form, i.e. the nomen actionis, which has primary stress on -átion. In sum, the phonologically aberrant behavior of these forms, together with their semantics, stresses the role of back-formation in the creation of -ate verbs.

The reader should note that eleven of the 25 ornative-resultative -ate verbs given in (Ornative/resultative -ate (2) discussed above are also attested later than their related action noun, which can be interpreted in such a way that these forms are not derived by suffixation, but are back-formations. This does, however, not challenge our analysis of ornative-resultative -ate verbs, but merely shows that the relationship of ornative-resultative -ate verbs with the corresponding -ation nouns is probably one of cross-formation (see Becker 1993a). The LCS in (Ornative/resultative -ate(1) should not be confused with a traditional word formation rule on the basis of which all ornative-resultative -ate verbs must be formed. What I have proposed instead is a semantic well-formedness condition for possible -ate verbs which does not entail claims about the morphological operation (affixation, back-formation, or conversion) by which they come into existence.

1 There are only two back-formed verbs on the basis of other nouns. Mono chromate is modelled on Monochromator, escalate1 on escalator.

2 See Haspelmath (1995) for a detailed discussion of affix reanalysis.

3 Note that the OED analyzes escalation as being derived by escalate + -tion. The dates of the first attestations, however, indicate a back-formation relationship (escalation 1938, escalate (in this sense) 1959).

4 The derivatives in (1) include those that do not conform to the LCS of productive -ate.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)