Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Stress assignment in English nouns: Pater (1995) OT model

المؤلف:

Ingo Plag

المصدر:

Morphological Productivity

الجزء والصفحة:

P168-C6

2025-02-04

961

Stress assignment in English nouns: Pater's (1995) OT model

I will briefly outline the general constraint hierarchy responsible for the stress patterns in English nouns, omitting a number of constraints not directly relevant for the present purposes. The specific phonological properties of -ize verbs result from the operation of constraints that occupy a lexically specified position in the general hierarchy. This is in line with the idea frequently expressed in the literature (e.g. Alber 1998, Benua 1995, 1997, Urbanczyk 1995, 1996) that members of derivational categories are subject to the general prosodic constraints of a language, but that these categories involve further faithfulness relations which enrich the general constraint hierarchy of the language. As we will see, such constraints do not only influence stress assignment, but also segmental stem alternations as those that can be observed with -ize derivatives.

The following of Pater's constraints are most important for the analysis of -ize verbs. They are also the ones that are highest in Pater's hierarchy. The constraints and their definitions are given in (1a), their hierarchical ordering is given in (1b):

(1)

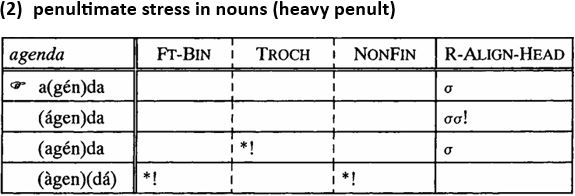

Basically, it is these four constraints that are responsible for the well-known generalization that English nouns are stressed on the penultima if it is heavy, and on the antepenultimate syllable if the penultima is light, (e.g Giegerich 1992:187, Burzio 1994:43). Let us see how this works. The constraints NONFINALITY and R-ALIGN-HEAD are in direct competition with each other. If NONFINALITY is ranked above R-ALIGN-HEAD, this forces main stress, and the main stressed foot, off the final syllable. R-ALIGN-HEAD nevertheless forces the main stress to be as close as possible to the right edge of the word, with each syllable intervening between the head syllable and the edge counting as one violation. Thus the minimal violation of R-ALIGN-HEAD which satisfies NONFINALITY is main stress on the penult. Consider the stress assignment in agenda and Canada (from Pater 1995:17-18):

The optimal candidate involves only one R-ALIGN-HEAD violation, whereas the competing candidates either violate higher ranked NON-FINALITY or show an additional R-ALIGN-HEAD violation. Note that, obviously, PARSE-σ must be ranked lower than R-ALIGN-HEAD, because the optimal candidate has two unparsed syllables. TROCH rules out the iambic candidate (agén)da, whereas Ft-BlN has no effect with these candidates. Turning now to words with non-heavy penult, we see that stress must be placed on the penultima in order to satisfy either of the top-ranked constraints:

Candidates that have a light penultima cannot have penultimate stress because in that case they would either have a final prosodic head, as in Ca(náda), or non-binary foot, as in Ca(ná)da, or an iambic foot, as in (Caná)da. With either of these candidates, one of the top-ranked constraints is violated.

Let us now turn to -ize derivatives, which show the same kind of basic stress pattern as nouns, in that they never have ultimate primary stress.1 They thus markedly differ from other verbs, which usually carry their stress on the last syllable, especially if it is superheavy (e.g. Burzio 1994: chapter 3). Consider the following data:

(4)

The behavior of canonical verbs must be due to a different ranking of the constraints in (1a) above. Thus, it could be argued that with underived verbs NONFINALITY ranks below R-ALIGN-HEAD. The details of such an account still need to be worked out, but need not concern us here any further. The basic points are that nouns behave differently from verbs, that derived verbs behave differently from underived verbs and that -ize verbs behave in general like nouns, but with some requirements that are specific to this class of words.

Note that it is not only derived verbs that do not behave like their un-derived counterparts, but that also certain derived nouns and adjectives show an aberrant behavior. Thus, nominal derivatives in -ee and -eer, or adjectives in -esque pattern with canonical verbs in that they have ultimate primary stress. The reasons for this anti-canonical prosodic behavior of certain classes of derived words certainly merit further investigation, but in general we can say that suffixes may bring in their own requirements which may disturb the general pattern.

1 As mentioned already in note 13, Hiberno-English and many varieties of Caribbean English place ultimate primary stress on -ize derivatives. The analysis to be proposed here does not extend to these varieties.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)