Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

CREATE THE IMAGE

المؤلف:

BARBARA MINTO

المصدر:

THE MINTO PYRAMID PRINCIPLE

الجزء والصفحة:

205-12

2024-10-02

1218

CREATE THE IMAGE

Here is a passage from Thoreau's Walden. As you read it, try to keep track of what's going on in your mind.

Near the end of March 1845 I borrowed an axe and went down to the woods by Walden Pond, nearest to where I intended to build my house, and began to cut down some tall, arrowy white pines, still in their youth, for timber… It was a pleasant hillside where I worked, covered with pine woods, through which I looked out on the pond, and a small open field in the woods where pines and hickories were springing up. The ice in the pond was not yet dissolved, though there were some open spaces, and it was all dark-colored and saturated with water.

As you took in the words, did you not build up a sort of mental picture in your mind, to which you added details as you took in successive phrases and sentences? What you were building was an image, but not a photographic image. Rather it is what George Miller, to whom I am indebted for this example,1· calls a "memory image," and it grows piecemeal as you go along.

If you read it as I did, first you see that it's March 1845, so that perhaps you have a feeling of a gray day in the past. Then you see one person borrow an axe from a second person, both indistinct, and you see him walking toward the woods, axe in hand. The trees turn into white pines, and you see Thoreau chopping at them. The next sentence introduces a hillside, so that suddenly the trees are on a hill. Then you see Thoreau stand up straight and look across at the pond, the open field, and the ice.

Your experience may or may not have been exactly like that. The point is, however, that you were constructing the passage as you read. The result of this constructive activity is a memory image that summarizes the information presented. You construct the image as part of the process of understanding, and the image then helps you to remember what you have read.

If you put the book down and try to remember what you read, you will probably find that you can't repeat it verbatim. But if you recall the image you can read off from it what you see, and it will be roughly equivalent to the original.

That images help to increase recall has been proven in memory studies, although these studies also show that people forget some details and embellish others, depending on their emotional predilections. Nevertheless, the memory image does provide a record of the passage and of the information extracted from it-a record that the reader constructs as he reads, phrase by phrase.

This is the kind of thing that must happen every time you read anything if you are to comprehend and remember it. Some passages are more difficult to visualize than others, and if the ideas being presented are particularly abstract, it may be that you will represent them with skeletal structures rather than with images. But unless the passage can be visualized in Some form, unless the reader can actually "see" what is being said, he cannot be considered to have understood it.

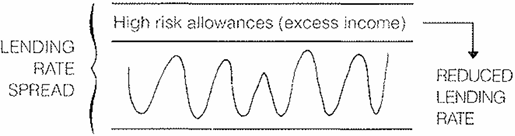

To demonstrate, here is a passage from a document that debated whether the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development should change front a fixed lending rate to a floating one.

If the risk allowances provided in the lending rate spread turn out to be too high, the Bank's income will be returned to borrowers as a group through a reduction in the lending rate in subsequent periods. Thus, fixed rate lending would involve extra costs for borrowers as a group only if the Bank were systematically to overestimate risks and thereby earn "excess" income more or less permanently This possibility seems remote.

Although the concepts discussed are fairly abstract, words like "spread," "excess," and "reduction" permit you to visualize a clear set of relationships. If asked to draw them, you could do so with no more than four lines and two arrows, perhaps like this. (I have added the words, but you would not need to do so for yourself.)

This skeletal nature of the image is important to note. One does not want a complete, detailed photographic reproduction, but only a sense of the structure of the relationships being discussed. These will generally consist of one or more geometric forms (e.g., circle, straight line, oval, rectangle), arranged in a schematized or sketchy fashion, plus something like an arrow to indicate direction and interaction.

It may seem almost childish as you look at it. But all the great "visual thinkers" of the past who have talked about it, front Einstein on down, have emphasized this vague, hazy; abstract nature of their conscious visual imagery.

1From "Images and Models, Similes and Metaphors," in Metaphor and Thought, Andrew Ortony, editor. Cambridge University Press, 1979.

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)