Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Un-stoppable?

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

114-6

2023-12-18

2096

Un-stoppable?

George Orwell’s famous novel Nineteen Eighty-Four presents a world in which the state conditions thought through control of language. The hero Winston Smith is charged with rewriting documents in ‘Newspeak’, a version of English in which the words to express opposition to the all-powerful Big Brother simply do not exist. Part of this involves removal of antonyms; thus ‘bad’ becomes ‘ungood’ and heretical statements beyond ‘Big Brother is ungood’ become all but impossible:

‘After all, what justification is there for a word which is simply the opposite of some other word? A word contains its opposite in itself.

Take "good", for instance. If you have a word like "good", what need is there for a word like "bad"? "Ungood" will do just as well — better, because it’s an exact opposite, which the other is not.’

Fortunately, language is far too complex, and human beings far too creative in its use, for top-down control ever to be possible. Ungood may never have caught on, but uncool has, and unfriend, while ruled out as a noun, has emerged as a verb with the advent of Facebook. What Orwell appears to have grasped is the flexibility with which English speakers apply this prefix to create antonyms:

But I’ve already booked a table!

- Well, unbook it!

I have even heard a speaker, known for his fondness for British understatement (litotes), observe that: ‘this actor doesn’t unremind me of a young Robert Redford’!

Our derivational inventiveness stems in part from the fact that we associate morphemes with a particular meaning, and learn those meanings in the same way we do those of full lexemes. But there is an interesting subset of derivational morphemes with no apparent meaning outside the isolated lexemes in which they occur. These have become known as cranberry morphemes after their most celebrated example:

straw+ berry

black+ berry

goose+ berry

blue+ berry

cran+ berry

All of these cases appear to involve compounding of free morphemes, but cran has no independent meaning or function outside of the word cranberry. A slightly more marginal case is lukewarm, in which the first element luke- appears to qualify warm and is thought to derive from a Middle English word meaning ‘tepid’, but has no such meaning in any other lexeme.

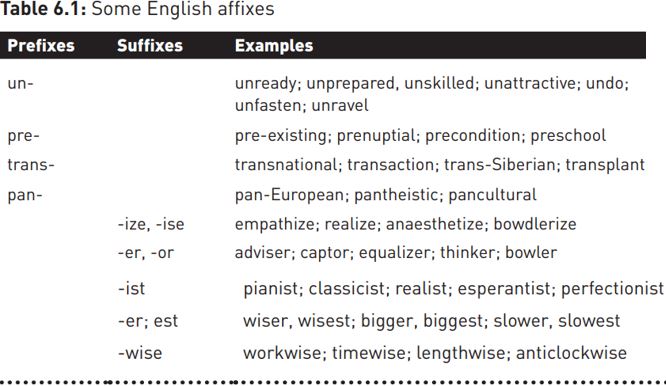

Children learn not just a list of derivational morphemes, which enables them to understand new words like giant-baking-soda-volcano-inator, but also the rules by which they may be combined. A child needs to know not just that prefixes can only be placed at the beginning of the word and suffixes at the end, but also that affixes attach to particular kinds of word-class.

The word uncontrollableness, for example, can be divided into four morphemes un+control+able+ness, but these morphemes have an internal constituent structure and are not simply juxtaposed. Control needs to combine first with able to form controllable, because the prefix un- can only attach to adjectives (unwary) and verbs (undo), but not nouns, ruling out *uncontrol. The same restriction applies to the abstract noun controllableness, which suggests that, in spite of the fact that controllableness does exist, the proper constituent structure is uncontrollable+ness rather than un+controllableness. This can be illustrated by the following tree diagram.

In the above example, morphologists would distinguish between root and stem morphemes: the root noun (in this case) around which uncontrollableness is built is control, which is also the stem of controllable. But controllable itself is the stem of uncontrollable, and likewise uncontrollable is the stem that yields uncontrollableness.

While many aspects of derivational morphology reveal regular patterns, much has to be learned on an item-by-item basis. In the example above, the meaning of the -ness suffix used for coining abstract nouns is broadly synonymous with that of -ity, and many speakers prefer uncontrollability to uncontrollableness (prescriptive dictionaries allow both). A quick Google search gave around 25,000 hits for uncontrollableness, but 241,000 for uncontrollability, but unfathomableness gave 41,600 hits as opposed to only 10,700 for unfathomability. The same highly unscientific test suggested a preference for unremarkableness over unremarkability but a strong preference the other way for predictability over predictableness. Similarly, there is no obvious reason why the antonyms of complete and capable are incomplete and incapable while those of conscious and comfortable are unconscious and uncomfortable: this is simply an arbitrary fact about present-day English.

Derivational morphology reveals many grey areas in which form or meaning can vary and change. The suffix -phobia, for example, has acquired a generally pejorative meaning in xenophobia and homophobia which it lacks in claustrophobia or agoraphobia, and while some speakers insist on the dictionary distinction between disinterested and uninterested, for many others the two words are now synonymous.

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)