Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

IMPOSING LOGICAL ORDER

المؤلف:

BARBARA MINTO

المصدر:

THE MINTO PYRAMID PRINCIPLE

الجزء والصفحة:

75-6

2024-09-13

1324

IMPOSING LOGICAL ORDER

be second rule of the Minto Pyramid Principle is that ideas in any grouping must be in logical order The logical order rule helps to make sure that the ideas you have brought together truly belong together, and that you have not left any out. In other words, you may have grouped together a set of ideas that can legitimately be labeled "steps," but unless you can put them in one-two-three order, you cannot be certain they are all part of the same process and that they are all there.

In deductive groupings, of course, finding the logical order is no problem, since it is the order imposed by the structure of the argument. In inductive groupings, however, you have a choice of how to order. Thus, you need to know how to make the choice, and how to judge that you have made the right choice.

To this end you must understand that, in theory’ ideas grouped together in ·writing are never brought there by chance. They are always picked out by your mind because it sees them as having a logical relationship. For example:

- Three steps to solve a problem

- Three key factors for success in an industry

- Three problems in a company.

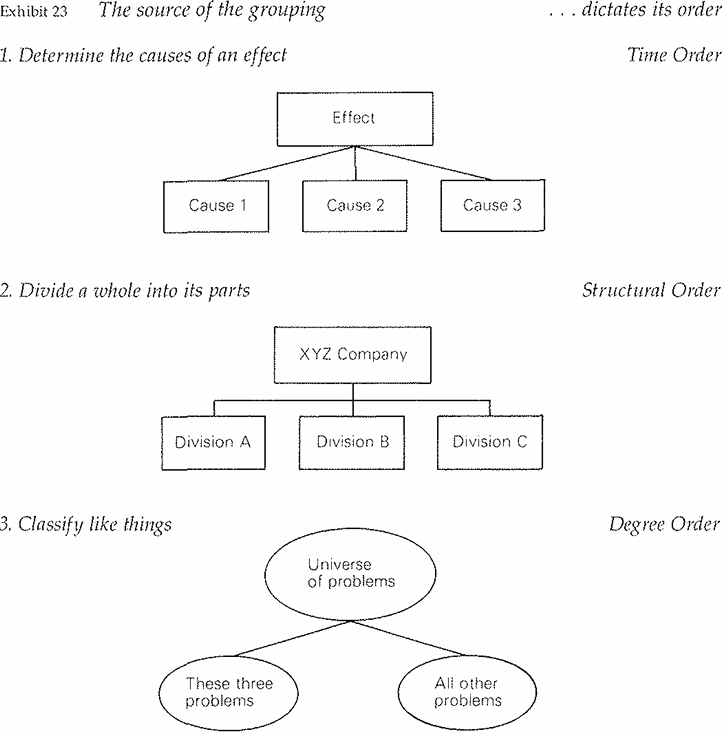

To see such relationships, the mind must have performed a logical analysis. In that case, the order you choose should reflect the analytical activity that your mind performed to create the grouping. The mind can perform only three analytical activities of this nature (Exhibit 23).

1. It can determine the causes of an effect. Whenever you make statements in writing that tell the reader to do something-fire the sales manager, say; or delegate profit responsibility to the regions-you do so because you believe the action will have a particular effect. You have determined in advance the effect you want to achieve, and then identified the action necessary to achieve it.

When several actions are together required to achieve the effect (e.g., three steps to solve a problem), they become a process or a system-the set of causes that in concert create the effect. The steps required to complete the process or implement the system can only be carried out one at a time, over time. Thus, a grouping of steps that represents a process or system always goes in time order; and the summary of the set of actions is always the effect of carrying out the actions.

2. It can divide a whole into its parts. You are familiar with this technique in creating organization charts or picturing the structure of an industry. If you are going to determine the "key factors for success in an industry", for example, you must first visualize the structure of that industry. Having done so, you determine what must be done well to succeed in each part of it. The resulting grouping of three or four key factors would then logically be ordered to match the order of the parts shown in the structure you visualized. This is structural order.

3. It can classify like things together. Whenever you say that a company "has three problems", you are not speaking literal truth. The company has many problems some total universe of problems-of which you have classified three as being note-worthy in some way compared to the others. You are saying that each possesses a characteristic by which you are able to identify it as a particular kind of problem -say because each one is the result of a refusal to delegate authority.

All three problems are the same in that each possesses this characteristic, but they are all different in that each possesses it to a different degree. (If they possessed it to the same degree, you could not distinguish them on this basis.) Because they are different, therefore, you rank them in the order in which they possess to the greatest degree whatever characteristic made you identify them as problems in the first place. This is variously called degree order, comparative order, or order of importance.

These orders can be applied singly or in combination, but one of them must always be present in a grouping to justify its existence. In other words, given that any grouping of ideas can have been created only through applying one of these three analytical frameworks, any grouping of ideas must have as its backbone one of these three orders. Thus you want deliberately to look for an order in each of your groupings. If you don't find one, it tells you instantly that there is something wrong with the grouping. And your knowledge of the underlying framework can help you sort out the problem.

Let me tell you more about each ordering framework and how you can use them to check your thinking.

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)