Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Productivity in meaning: semantic regularity

المؤلف:

Andrew Carstairs-McCarthy

المصدر:

An Introduction To English Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

88-8

2024-02-03

1680

Productivity in meaning: semantic regularity

A derivational process is semantically regular if the contribution that it makes to the meaning of the lexemes produced by it is uniform and consistent. An example is adverb-forming -ly. This is not only formally regular (like -ness) but also semantically regular, in that it almost always contributes the meaning ‘in an X fashion’ or ‘to an X degree’. Semantic and formal regularity can diverge, however. Again, the suffix -ity provides handy illustration. As we have seen, -ity nouns are formally regular when derived from adjectives with a range of suffixes such as -ive, -al and -ar, and the nouns selectivity, locality, partiality and polarity all exist. It may strike you, however, that none of these nouns means exactly what one might expect on the basis of the meaning of the base adjective. Selectivity has a technical meaning related to radio reception, not shared with selectiveness, which has only the expected non-technical meaning. The adjective local can mean ‘confined to small areas’, but locality means never ‘confinement to small areas’ but always ‘neighborhood’. The noun partiality can mean either ‘incompleteness’ or ‘favorable bias’, just as partial can mean either ‘incomplete’ or ‘biased’; however, the noun more often has the second meaning while the adjective more often has the first. And one can use the noun polarity in talking about electric current, but not in talking about the climate in Antarctica.

Similar behavior is exhibited by the adjective-forming suffix -able. This is formally regular and general; the bases to which it can attach are transitive verbs, and there is scarcely any transitive verb for which a corresponding adjective in -able is idiosyncratically lacking, including a brand-new verb such as de-Yeltsinise. We have already drawn attention to the fact that -able adjectives can exhibit semantic irregularity, as readable and punishable do. In the same exercise, too, we noted that words formed with the suffix -ion and even some words with the formally highly regular -ly and -ness are not entirely predictable in meaning.

This divergence between formal and semantic regularity in derivation contrasts sharply with how inflection behaves. There, semantic regularity is the norm even where formal processes differ; for example, no past tense form of a verb has any unexpected extra meaning or function, whether it is formally regular (e.g. performed) or irregular (e.g. brought, sang). This contrast is not so surprising, however, if one remembers that word forms related by inflection are all forms of one lexeme, and therefore necessarily belong to one lexical item, whereas word forms related by derivation belong to different lexemes and therefore, at least potentially, different lexical items. Although, a lexeme does not necessarily have to be listed in a dictionary, lexemes have a kind of independence from one another that allows them to drift apart semantically, even though it does not require it.

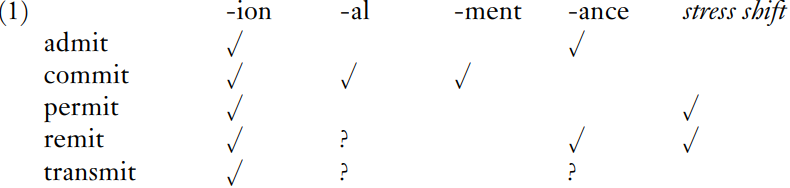

Another illustration of how semantic and formal regularity can diverge is supplied by verbs with the bound root -mit. We noted that the three nouns commitment, committal and commission all have meanings related to meanings of the verb commit, but the distribution of these meanings among the three nouns is not predictable in a way that would allow an adult learner of English to guess it. Also, there is no way that a learner could guess that commission can also mean ‘payment to a salesperson for achieving a sale’, because this is not obviously related to any meaning of the verb. It follows that the suffixation of -ion is by no means perfectly regular semantically. But consider its formal status, by comparison with other noun-forming suffixes, as shown in (1):

(The question marks indicate words which are not in my active vocabulary but which I would not be surprised to hear; indeed, transmittance exists as a technical term in physics, meaning ‘measure of the ability to transmit radiation’.) The pattern of ticks, question marks and gaps seems random – except for the consistent ticks in the -ion column. It seems that -ion suffixation is formally regular with the root -mit; that is, for any verb with the root -mit, there is guaranteed to be a corresponding abstract noun in -mission. That being so, it seems natural to expect that the meanings of these nouns should be entirely regular. Yet we have already seen that for commission this is not so. Remission, too, is semantically irregular, in that the meanings of remit and -ion are not sufficient to determine the sense ‘temporary improvement during a progressive illness’. So the fact that a noun in -mission is guaranteed to exist for every verb in -mit does not mean that, for any individual such noun, a speaker who encounters it for the first time will be able to predict confidently what it means.

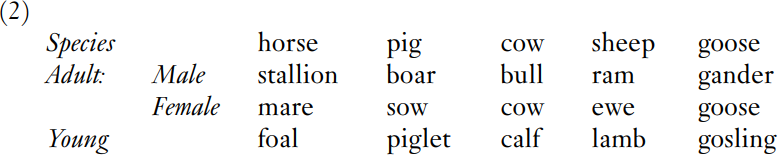

The converse of the situation just described would be one in which a number of different lexemes (not just inflectional forms of lexemes) exhibit a regular pattern of semantic relationship, but without any formally regular derivational processes accompanying it. Such a situation exists with some nouns that classify domestic animals according to sex and age:

Not many areas of vocabulary have such a tight semantic structure as this. However, the existence of just a few such areas shows that reasonably complex patterns of semantic relationship can sustain themselves without morphological underpinning. Morphology may help in expressing such relationships (as with pig and piglet, goose and gosling), but it is not essential. This reinforces further the need to distinguish between two aspects of ‘productivity’: formal and semantic regularity.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)