Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

More elaborate word forms: compounds within compounds

المؤلف:

Andrew Carstairs-McCarthy

المصدر:

An Introduction To English Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

76-7

2024-02-03

1473

More elaborate word forms: compounds within compounds

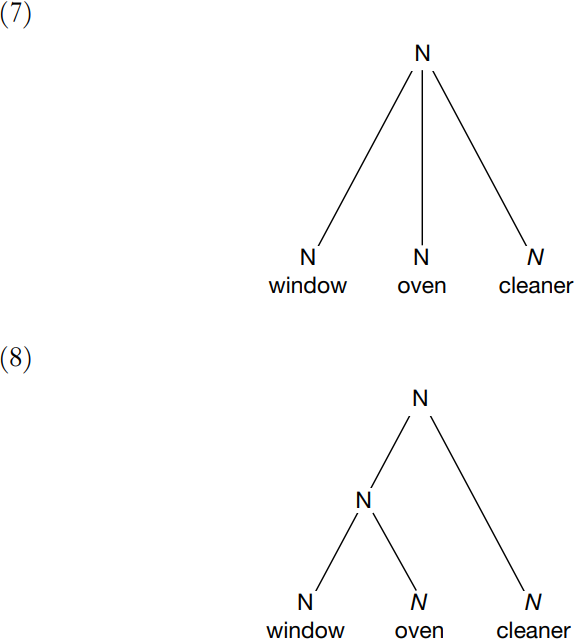

We saw that the structure of words derived by affixation can be represented in tree diagrams where each branch has at most two branches. The same applies to compounds: any compound has just two immediate constituents. All the compounds that were discussed contained just two parts. This was not an accident or an arbitrary restriction. To see this, consider for example the noun that one might use to denote a new cleaning product equally suitable for ovens and windows. Parallel to the secondary compound hair restorer are the two two-part compounds oven cleaner and window cleaner. Can we then refer to the new product with a three-part compound such as window oven cleaner? The answer is surely no. Window oven cleaner is not naturally interpreted to mean something that cleans both windows and ovens; rather, it means something that cleans window ovens (that is, ovens that have a see-through panel in the door). This is a clue that its structure is not as in (7) but as in (8):

The structure at (8) seems appropriate even for complex compounds such as verb–noun contrasts and Reagan–Gorbachev encounters. As simple compounds, verb–noun and Regan–Gorbachev certainly sound odd. Nevertheless verb–noun contrasts denotes crucially contrasts between verbs and nouns, not contrasts some of which involve verbs and others of which involve nouns; therefore verb–noun deserves to be treated as a subunit within the whole compound verb–noun contrast. Likewise, a Reagan– Gorbachev encounter necessarily involves both Reagan and Gorbachev, not just one of the two, so Reagan–Gorbachev deserves to be treated as a subunit within Reagan–Gorbachev encounters.

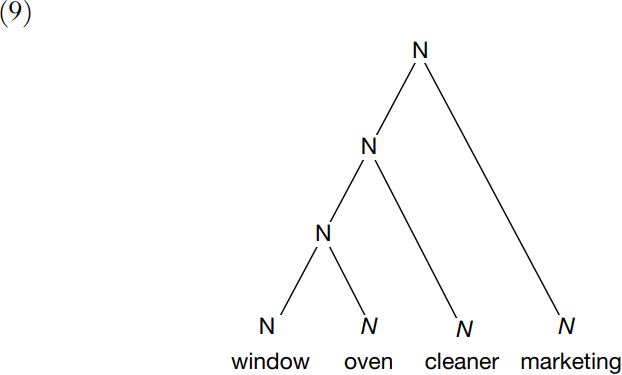

We concentrated on compounds with only two members. But, given that a compound is a word and that compounds contain words, it makes sense that, in some compounds, one or both of the components should itself be a compound – and (8), with its most natural interpretation, shows that this is indeed possible, at least with compound nouns. Moreover, the compound at (8) can itself be an element in a larger compound, such as the one at (9) meaning ‘marketing of a product for cleaning window ovens’:

At this point, it is worth pausing to consider whether these more elaborate examples comply with what was said about where stress is placed within compound nouns. Window oven, if it is a compound, should have its main stress on the lefthand element, namely window – and that seems correct. The same applies to window oven cleaner: its main stress should be on window oven, and specifically on its lefthand element, namely window. Again, that seems correct. So we will predict that the whole compound at (9) should have its main stress on the lefthand element too – a prediction that is again consistent with how I, as a native speaker, find it most natural to pronounce this complex word. It is true that other elements than window can be emphasized for the sake of contrast: for example, I can envisage a context at a conference of sales executives where one might say We are concerned with window oven cleaner márketing today, not with manufácture. Nevertheless, where no contrast is implied or stated (such as between marketing and manufacture), the most natural way of pronouncing the example at (9) renders window the most prominent element.

Can we then conclude that all complex compound nouns follow the left-stressed pattern of simple compound nouns? Before saying yes, we need to make sure that we have examined all relevant varieties. It may have struck you that, in (8) and (9), the compounds-within-compounds are uniformly on the left. We have not yet looked at compounds (or potential compounds) in which it is the righthand element (in fact, the head) that is a compound. Consider the following examples:

Native speakers are likely to agree sith me that, whereas in (10) the main stress is on holiday, in (11) it is on car. (Again, we are assuming that no contrast is implied – between a holiday trip and a business trip, say.) This is consistent with car trip being a compound with car as its lefthand element, but not (at first sight) with an analysis in which holiday car trip is a compound noun with holiday as its lefthand element. The stress on the righthand element in holiday car trip makes it resemble phrases such as green hóuse and toy fáctory, rather than compounds such as gréenhouse and tóy factory. Yet it would be strange if a compound noun cannot itself be the head of a compound noun, given that any other kind of noun can be.

The best solution seems to be to qualify what was said about stress in compound nouns. The usual pattern, with stress on the left, is overridden if the head is a compound. In that case, stress is on the right – that is, on the compound which constitutes the head. Another way of expressing this is to say that the righthand component in a compound noun gets stressed if and only if it is itself a compound; otherwise, the lefthand component gets stressed. As well as with native speakers’ intuitions about pairs such as (10) and (11). It is also consistent with a more complex example such as (12), involving internal compounds on both left and right branches. If you apply carefully to (12) the formula that we have arrived at, you should find that it predicts that the main stress should be on sight – which seems correct.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)