Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Grice on speaker meaning

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

85-4

6-5-2022

1131

Grice on speaker meaning

Grice was interested in a particular kind of meaning, namely, meaning that was neither “natural” nor purely “conventional” in nature, as one of his primary goals was to better understand how it is that speakers can mean something. He first clarified that the sense of meaning he was interested in differed from natural meaning, which is defined as instances where a certain sign is causally related to an event or concept (e.g. “Those clouds mean rain”). He then proposed that non-natural meaning (meaning nn) includes, but is not exhausted by, linguistic (or word) meaning, where the latter is defined as signs that are conventionally related to a concept (e.g. “dog” in English means an animal which normally has four legs, a tail, barks and so on). Instead, he proposed that meaning nn arises through the speaker having a specific kind of meaning intention. He defined this kind of complex intention in the following way (where “A” refers to the speaker and x refers to the utterance):

‘A meant nn something by x’ is (roughly) equivalent to ‘Auttered x with the intention to produce some effect in an audience by means of the recognition of this intention.’ (Grice [1957] 1989: 220)

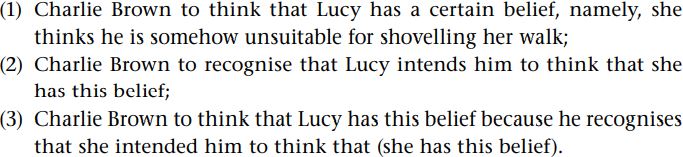

This definition of intention, while complex, is critical for us to understand as it underpins much, if not most, of the theorizing of pragmatic meaning representations to date. The essential idea is that a speaker means something by intending that the hearer recognize what is meant as intended by the speaker. What is meant is generally that the speaker has a particular belief, thought, desire, attitude, intention and so on. In other words, meaning nn necessarily involves the speaker thinking about what hearers will think he or she is thinking. This complex intention was further broken down into three levels by Grice (where “U” refers to the utterer, x refers to the utterance, and “A” refers to the audience):

Intention (1) is a first-order intention to produce a particular response in the hearer, which is embedded in a second-order intention (2) that the hearer recognize this first-order intention, which is further embedded in a third-order intention (3) that the hearer have this response on the basis of recognizing the speaker’s second-order intention.

As all this is somewhat hard to follow in the abstract, we will apply it here to a concrete instance of language use. Let us return to example [4.1] from Peanuts (the dialogue is extracted here as [4.2]):

Here Lucy could be said to be (speaker) meaning nn through uttering You? that she thinks Charlie Brown is somehow unsuitable for shoveling the snow outside her house by intending:

A number of scholars have claimed that the above third-order intention is unnecessary for defining speaker meaning (Bara 2010; Searle 2007). Indeed, one might argue that the last kind of intention raises the question of whether Grice’s notion of meaning nn is an abstract, theoretical notion of speaker meaning, or is something that is taken to actually arise in communication. At this point, however, the take-home message is that, following Grice, pragmatic meaning representations are generally understood as the speaker’s reflexively intended mental state. In other words, a speaker’s belief, thought, desire, attitude, intention and so on, which is intended by the speaker to be recognized by the hearer as intended.

Grice divided his notion of meaning nn or speaker meaning into two broad types of representation: what is said and what is implicated. He proposed that what is said can be traced to a certain understanding of saying involving meaning that is “closely related to the conventional meaning of the words (the sentence) [the speaker] has uttered” (Grice [1975]1989: 25). He elaborated this further in claiming that what is said is closely related to “the particular meanings of the elements of S [sentence], their order, and their syntactical character” (ibid.: 87). In other words, for Grice, what is said is compositional, as it arises through a combinatorial understanding of word meaning, syntax, and processes of reference assignment, indexical resolution and disambiguation (the latter referring to both different senses of words and different possible syntactic structures).

To illustrate what Grice meant by what said, let us recall Charlie Brown’s offer to Lucy to clean up the snow on the path leading to her house.

In order to understand what is said by Charlie Brown, we need to work out the underlying syntactic structure of his utterance (i.e. shovel is a verb referring to a particular type of action, and your walk is a noun phrase, namely, the object of that action), the referent of your (i.e. the second person pronoun refers to Lucy), and disambiguate what sense of walk is meant here (i.e. it refers to a path not the action of walking) amongst other things. However, if you recall we have already largely discussed such processes, and so will not consider them further here.

Grice’s account of what is said was arguably not very well developed, as he left it as primarily a matter for semantics to deal with. Instead, his primary focus was the second main type of meaning representation that he had proposed, namely, what is implicated. We will be returning to the issue of whether what is said really is just a semantic notion, as assumed by Grice. However, before doing so we move to consider Grice’s notion of what is implicated in more detail.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)