Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Foregrounding

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

64-3

30-4-2022

1052

Informational foreground

Foregrounding

In informational pragmatics, scholars have not fully explained what it is that pushes information into the foreground and makes it salient. Some work done on the pragmatic-grammar interface has addressed more formal aspects of foregrounding, and we will consider some of this work . Nevertheless, too many studies simply refer to, for example, something having been recently mentioned as evidence that it is in the foreground. There is much more to it than this. A key theory to turn to here is the theory of foregrounding. This theory does not restrict its focus to the sentence, but can work at various linguistic levels. It is concerned with how language can be made cognitively salient, with – recalling our distinction between semantic givenness/newness and cognitive givenness/newness – cognitive focus. Though rooted in Russian Formalism and the work of the Prague School, its main development came about in the 1960s and after in literary studies, discourse analysis and cognitive psychology. Foregrounding theory has been shown to guide the interpretation of literary texts (van Peer 1986), though there is no reason for limiting it to literary texts since it encapsulates general principles.

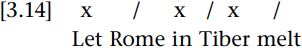

Foregrounded elements achieve salience through deviation from a linguistic norm (Mukarovský 1970). This idea is analogous to that of figure and ground. The characteristics of such foregrounded elements include “unexpectedness, unusualness, and uniqueness” (ibid.: 53–54). Unexpectedness is a notion that is not remote from cognitive newness as opposed to givenness . Consider an example of foregrounding. In Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra, when Anthony says, Let Rome in Tiber melt (I.i.33), deviation occurs at a semantic level, since, quite obviously, a city cannot melt. Our attention is captured and we can work to construct an interpretation. Leech (1985) drew attention to the two sides of foregrounding: just as you can have deviation through irregularity, so you can also have deviation through regularity. The parallelism of the same kinds of elements where you would normally expect different ones is a type of deviation. In the above example, one can perceive a high degree of regularity in the metrical pattern:

The strict alternation between stressed and unstressed syllables picks this utterance out. It is foregrounded not only against the natural rhythms of spoken English, but also against the immediately preceding lines which contain no such regularity of patterning. This regularity helps foreground the serious nature of what Anthony has to say, his first statement of treason. There is also some degree of syntactic foregrounding. Syntactic norms are violated in that no definite article precedes Tiber. Furthermore, the ordering of this particular clause, the adverbial falling between subject and verb, seems odd. Perhaps the syntactic construction here was motivated by a desire to form a regular metrical pattern.

One of the main reasons for the success of the notion of foregrounding lies in its relevance to the study of the process of linguistic interpretation. Leech (1985: 47) points out that more interpretive effort is focused on foregrounded elements in an attempt to rationalize their abnormality, than on backgrounded elements. Leech writes:

In addition to the normal processes of interpretation which apply to texts, whether literary or not, foregrounding invites an act of IMAGINATIVE INTERPRETATION by the reader. When an abnormality comes to our attention, we try to make sense of it. We use our imaginations, consciously or unconsciously, in order to work out why this abnormality exists. (Leech 1985: 47)

Furthermore, van Peer (1986) has provided empirical evidence to substantiate the claim that foregrounded elements are not only cognitively more striking but are also regarded as more important in relation to the overall interpretation of the text.

Foregrounding theory is generally focused on implicit foregrounding, achieved by making certain elements cognitively salient and thus likely to attract more attention. Sometimes, language deploys explicit foregrounding. An example of this is when we write in this topic “note that ...”. Here, we are explicitly directing you towards parts of the text which we think are important and so should be in the foreground of your attention (you can always ignore the instruction of course!). There are, needless to say, other structures that involve that kind of explicit direction and we will attend to some of them, amongst other things.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)