Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Reflection: Social deixis across languages

المؤلف:

Reflection: Social deixis across languages

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

26-2

23-4-2022

957

Reflection: Social deixis across languages

Person marking varies hugely from language to language. Consider, for example, that Fijian is said to have 135 person forms, whereas Madurese, an Austronesian language, has only two (Siewierska 2004: 2). One of the reasons for this is that person marking interacts with the socio-cultural contexts of the particular language. As Mühlhäusler and Harré (1990: 207, quoted in Siewierska 2004: 214) comment, “pronominal grammar provides a window to the relationship between themselves and the outside world”. Obviously, this fact is most salient with respect to social deixis. Non-singular second person marking when addressing a single person is often a way of signaling social distance, deference (particularly in the context of an age differential) or formality, as was the case, at least to some extent, with the you-forms in earlier periods of English, and is still the case in many European languages (e.g. French, German, Spanish, Greek, Danish, Swedish, Russian, Czech). Non-singular person marking is also used for single referents in many other languages, but not necessarily for the same social reasons. Some languages achieve such social functions with the use of the third person. For example, in Italian one uses the third person feminine singular lei, and in German the third person plural Sie. Such person marking phenomena are part of linguistic honorifics, conventional systems of forms that “honor” (i.e. express deference to) a participant (usually but not necessarily the addressee) in some way. Such forms include not only person markings, but also forms of address, various affixes, clitics and particles, and choice of vocabulary. Present-day English does not have a rich honorific system, being now largely confined to forms of address, as noted above. Other languages, particularly those of East and South-East Asia (e.g. Thai, Japanese, Nepali, Korean) have remarkably rich systems. In Thai, there are said to be 27 forms used for the first person, 22 for the second and eight for the third. These are used according to, amongst other things, social status, intimacy, age, sex and kinship, and to reflect deference or assertiveness (see Cooke 1968, quoted in Siewierska 2004: 228).

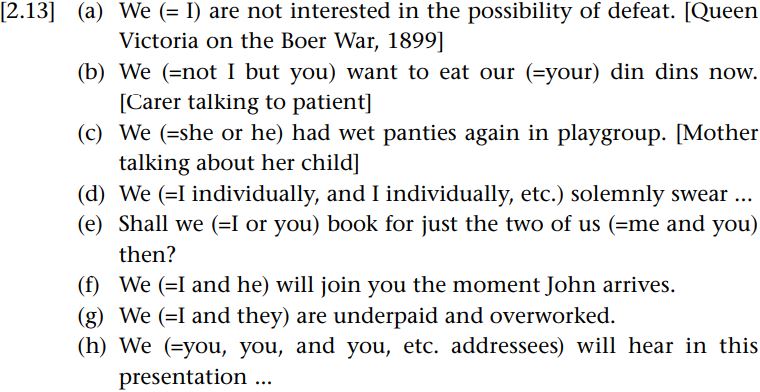

Person markers, as we have seen for all referring expressions, are not always used in such a way that their encoded meaning matches their usage. Mismatches are often deployed for the purpose of generating local social meanings. Consider, for example, the range of possible referents for the English form we (based on the list given in Siewierska 2004: 215):

Some of these mismatches have become well established. (a) is of course the royal-we (pragmatically “I”), a more recent example of which are the words of Margaret Thatcher upon discovering that she had become a grandmother in 1989: we have become a grandmother. The royal-we might be said to be a case of self-deference: the speaker is the honorific focus. (b) is a typical usage of the exclusive-we (pragmatically not “I”), where the avoidance of the pronoun you in requests or commands lends a veneer of politeness (see Wales 1996, for a full discussion of we and other English pronouns).

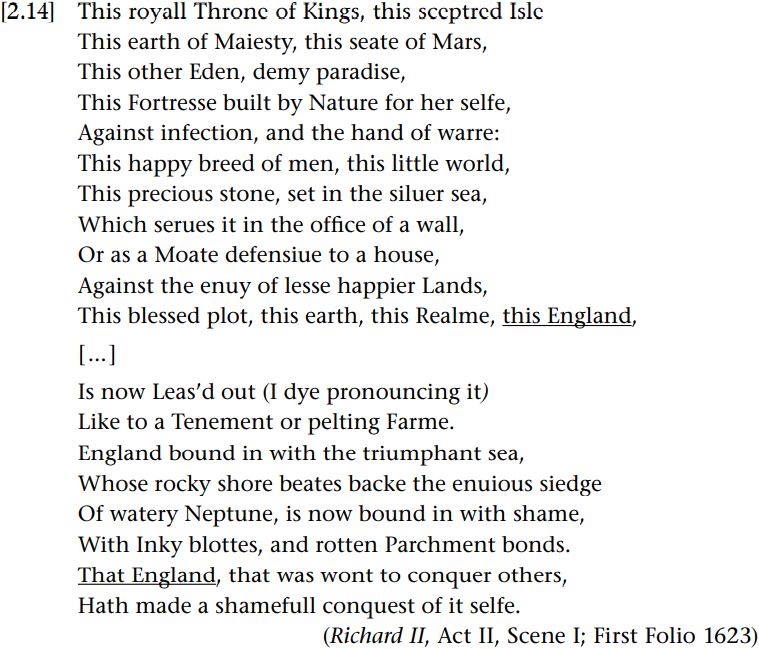

As can be seen from Table 2.2, a category of deictic expressions can express spatial relations. As far as English is concerned, spatial deixis typically expresses a relationship relating to distance between the deictic centre of the speaker and a referent. English has a proximal/distal (as in near/far) contrast, as might be illustrated by items such as here/there and this/that. However, usage of these items, particularly the final set of demonstratives, is not always restricted to physical spatial relations. In the extract from Shakespeare below, John of Gaunt laments the fact that England is not what it was; England has been sold out by Richard II, the current king, in pursuit of his own glory. The contrast is between proximal this England, near in time, and distal that England, further away in time.

We might also briefly note that sometimes the issue is one of focusing the target’s attention. Thus, while here in Here she is! might well convey the fact that somebody has arrived in the vicinity, it also draws attention to that fact; and that in I’d like that one (said of several items all the same distance from the speaker) focuses the target’s attention on one particular item.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)