Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

How to: morphological analysis

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

110-6

21-1-2022

2047

How to: morphological analysis

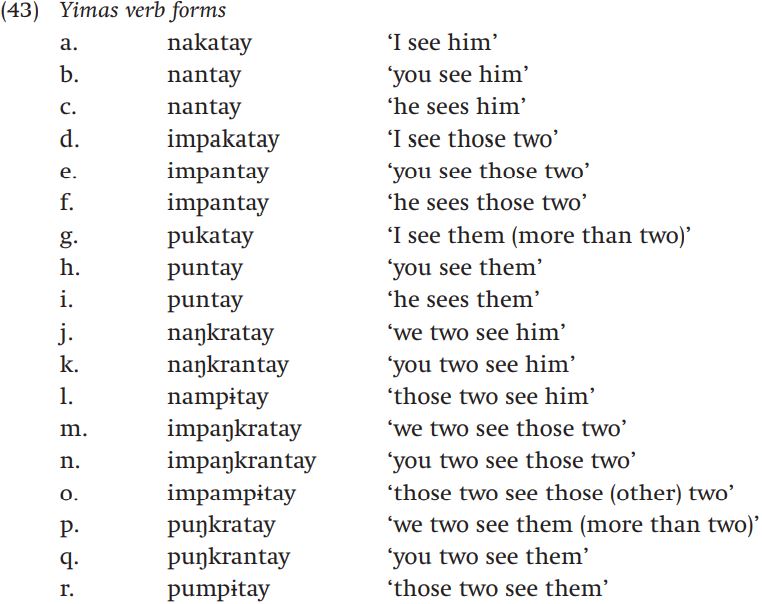

We will try to expose you to some of the sorts of inflectional distinctions that you might expect to find outside of English. Reading about inflectional morphology is not the same as analyzing it though. As a student morphologist you should be ready to figure out what sorts of inflectional distinctions are expressed in an unfamiliar language and how they are expressed. we will simulate such an experience for you, and take you through the process of trying to analyze the inflectional morphology of a language you otherwise know little or nothing about. Our example comes from the Papuan language Yimas, spoken in New Guinea (Foley 1991: 217):

Analyzing the inflectional system of an unfamiliar language is not very different from analyzing the sort of derivational data. What we do to start off is to look at glosses, and compare forms for areas of overlap.

If you glance even casually at the data in (43), you’ll see that I’ve given you part of a verb paradigm, namely the verb ‘to see’ in Yimas. You might therefore expect to find something that occurs in every form that would correspond to the root meaning ‘see’. Scanning the data, you will see that almost every form except s, v, and y ends in the sequence tay. The three forms that don’t end in tay end in cay. It would be a good initial guess, then, that the morpheme for ‘see’ is tay. Since cay looks a lot like tay, we might hypothesize that it also means ‘see’, although we don’t yet know why those three forms are different. At this point, let’s set aside the three forms with cay to think more about later.

The next thing we notice about the forms in (43) is that they vary in the person and number of the subject: there are examples with first, second, and third person subjects, not only in singular and plural, but also apparently in the dual. So Yimas makes a three-way number distinction in its verb forms. We notice as well that the examples differ from one another in the number of their object (again singular, dual, and plural), although all of the object forms in these examples happen to be in the third person. Given that we already suspect that the verb root comes at the end, we would guess that subject and object are marked on the verb with prefixes. So our next task is to start comparing the various forms that have the same number object or the same person and number subject to see if we can find separate prefixes for subject and object.

Let’s start with the object forms. If you look at (43a–c), you’ll notice that all three forms begin with na-, but that (43a) has ka- after the na-, whereas in (43b, c), there’s an n- after na-. We can hypothesize, then, that na- must mean ‘he-object’, but we need to check ourselves to make sure that other forms in (43) with third person singular objects begin with na-. If we look at (43j, k, l), you’ll see that our hypothesis is confirmed, and if you look further down the data, you’ll also see na- at the beginning of (43s, t, u). Now, looking at (43d, e, f ), you’ll notice that all three forms begin with impa-; in (43d) this is followed by ka- and in (43e–f) by n-. We can guess then that impa- must mean third person dual object. Finally (43g, h, i) all begin with pu-; again in (43g) pu- is followed by ka- and in (43h–i) by n-. It looks like pu- is used for a third person plural object.

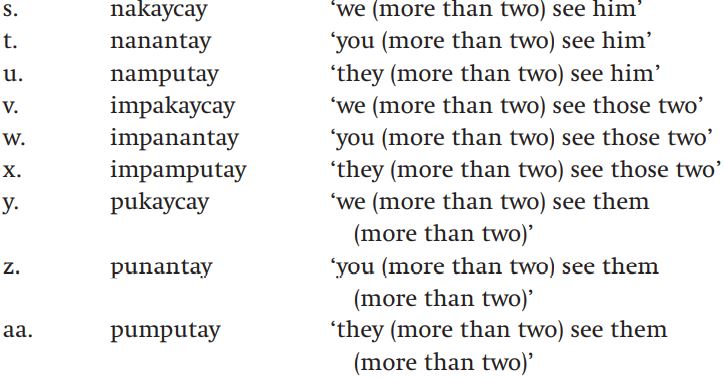

If na- is the third person object marker, then what’s left over between it and the verb stem must be the subject marker: in (43a, b, c), this would leave ka- as the first person singular subject marker, and n- for both the second and third person singular subject markers (syncretism!). Now, if you peel off the other object markers impa- and pu- from the beginnings of the words, and tay/cay from the end of the words, what you have left should be all the subject markers. This is what we get:

Beginning students might have the impulse to call the subject markers ‘infixes’, because they occur between the object markers and the verb root, but they are not infixes. Remember that we only call an affix an infix if it occurs within another morpheme. What we have here instead is a sequence of two prefixes before the verb root. So the structure of the Yimas verb is:

A note about the Yimas data: we still haven’t explained why the verb root appears to be tay in most verb forms but cay in (41s, v, and y). With the data I’ve given you, it’s actually impossible to say anything more about these forms. This is a point at which you, as the morphologist studying an unfamiliar language, must go looking for more data in the hope that they will explain what’s going on. So here’s a cautionary note: linguistic data can sometimes be a bit messy. Introductory text books have a tendency to sanitize data so that the student linguist will not be confronted with bits that can’t be explained. But keep in mind that in the real world data are rarely perfectly sanitary. You often see a pattern, but it’s not always perfect. This may be frustrating, but it isn’t a bad thing – every bit of mess – or apparent mess – forces us, as linguists, to keep looking for more data and to look more carefully at the data we have.

A final note: if you look carefully in Foley’s (1991) grammar of Yimas, it appears that there is a phonological rule that turns [t] to [c] if it is preceded by [y].5 So we were right to guess that tay and cay are the same morpheme.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)