Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Why English has so little inflection

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

101-6

21-1-2022

2764

Why English has so little inflection

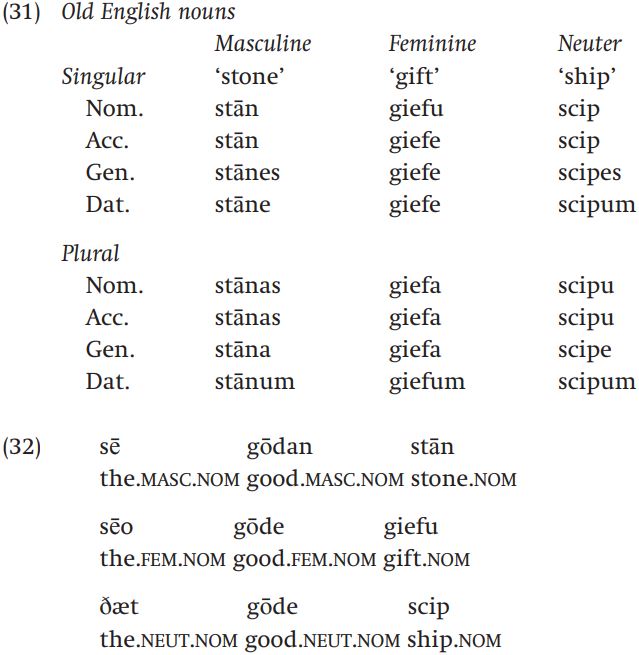

You might wonder why English has so little inflection. In fact, if you study the history of English, you’ll find that at one time English had quite a bit more inflection than it now has. The earliest form of English, Old English, was spoken from about 450 to 1100 CE. Old English had three genders – masculine, feminine, and neuter – and a case system with four cases – nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive, see (31). Articles and adjectives agreed with nouns in case and number, as (32) shows:

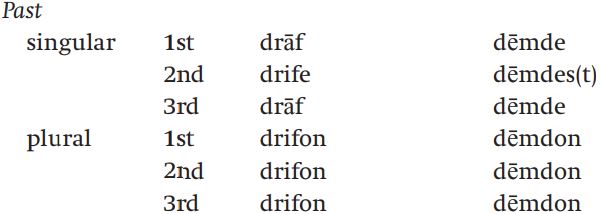

Verb inflection was also more complex in Old English than in Modern English. In Old English, verbs were inflected for person and number, and were different for present tense and past tense in both the indicative and the subjunctive. In addition, some verbs were strong verbs, which means that they show internal stem change – specifically ablaut – in some forms. For example, in the strong verb drīfan ‘to drive’ the present tense always has a long [i] vowel, but the past has the vowel [a] in the first and third person singular and a short [i] in the plural form and the second person singular. Other verbs were called weak verbs; these inflected using suffixes rather than ablaut. As you can see with the weak verb dēman ‘to judge’ in (33), the vowel of the stem never changes, but in the past tense there is always a suffix -d(e):

Why did English lose all this inflection? There are probably two reasons. The first one has to do with the stress system of English: in Old English, unlike modern English, stress was typically on the first syllable of the word. Ends of words were less prominent, and therefore tended to be pronounced less distinctly than beginnings of words, so inflectional suffixes tended not to be emphasized. Over time this led to a weakening of the inflectional system. But this alone probably wouldn’t have resulted in the nearly complete loss of inflectional marking that is the situation in present day English; after all, German – a language closely related to English – also shows stress on the initial syllables of words, and nevertheless has not lost most of its inflection over the centuries.

Some scholars attribute the loss of inflection to language contact in the northern parts of Britain. For some centuries during the Old English period, northern parts of Britain were occupied by the Danes, who were speakers of Old Norse. Old Norse is closely related to Old English, with a similar system of four cases, masculine, feminine, and neuter genders, and so on. The actual inflectional endings, however, were different, although the two languages shared a fair number of lexical stems. For example, the stem bōt meant ‘remedy’ in both languages, and the nominative singular in both languages was the same. But the nominative plural in Old English was bōta and in Old Norse bótaR. 2 The form bóta happened to be the genitive plural in Old Norse. Some scholars hypothesize that speakers of Old English and Old Norse could communicate with each other to some extent, but the inflectional endings caused confusion, and therefore came to be de-emphasized or dropped. One piece of evidence for this hypothesis is that inflection appears to have been lost much earlier in the northern parts of Britain where Old Norse speakers cohabited with Old English speakers, than in the southern parts of Britain, which were not exposed to Old Norse. Inflectional loss spread from north to south, until all parts of Britain were eventually equally poor in inflection.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)