Historical changes in productivity

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

67-4

الجزء والصفحة:

67-4

19-1-2022

19-1-2022

1062

1062

Historical changes in productivity

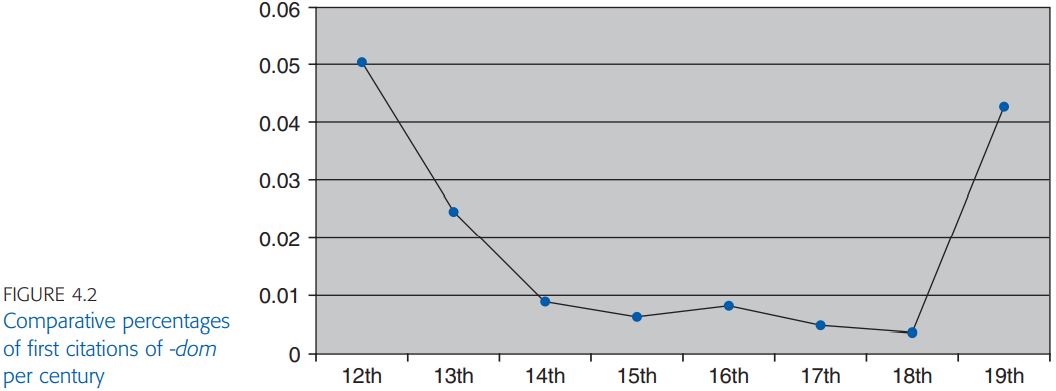

It should not come as a surprise at this point that lexeme formation processes may change their degree of productivity over time. Consider, for example, the suffix -dom in English, which attaches (mostly) to nouns and forms nouns. We find it in such words as chiefdom, fandom, and stardom. Not too much work has been done on methods of measuring productivity over time, but here is one very rough idea of how to do it. With some care, it’s possible to find all the words in the OED with the suffix -dom and take note of when they were first cited (in other words, the year of the first quotation the OED gives for their use). We can then count up how many -dom words were first cited in each century. If we also know how many citations there are in the OED for each century (not every century has the same number of citations), we can calculate what percentage of them are first citations with -dom. For example, if the OED gives 28,698 citations dating from the thirteenth century, and seven of them are the first citations of words with -dom, then the -dom citations represent 0.0243% of all the citations. I’ve calculated these percentages for each century, and then plotted them on a graph, as you can see in figure 4.2.

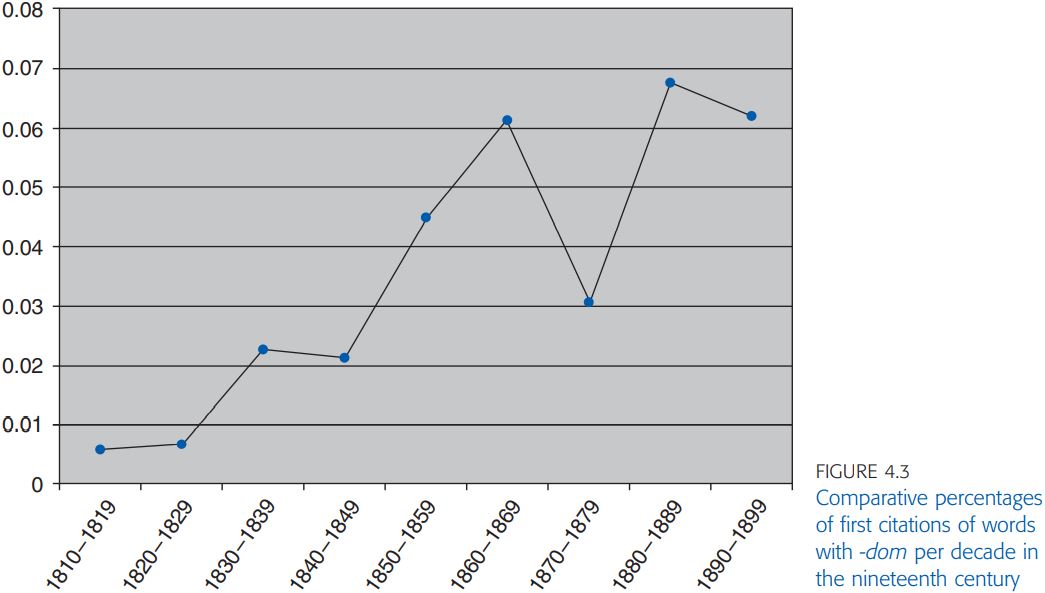

The suffix -dom is a very old one, going back to the beginnings of English, and indeed further back into the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family, from which English descends.1 We can see that after an initially very productive period in the twelfth century, -dom seems to have dropped off in productivity from the fourteenth through the eighteenth centuries. But its productivity rises again precipitously in the nineteenth century. In fact, we can see from figure 4.3 that if we look in detail at the percentage of first citations per decade in the nineteenth century, the suffix gained steadily in productivity as the century progressed (with an odd blip in the 1870s), and peaked in the 1880s.

Exactly why the productivity of the suffix should start to rise after centuries of minimal productivity is unclear. Wentworth (1941) notices the same trend that I’ve shown here, and points out that particular nineteenth-century authors seem especially prone to coin new words with the suffix: Thomas Carlyle and William Makepeace Thackeray in Britain, Mark Twain and Sinclair Lewis in the United States. But whether they are the cause of the rise or a reflection of something that was happening in the language at large is impossible to say. Bauer (2001) points out that in the nineteenth century, the kind of bases available to the suffix -dom seemed to expand drastically. Where it was confined for many centuries to bases referring to important types of people (lord, king, master, pope, earl, but also martyr and witch) or a few adjectives (wise, rich, free), in the nineteenth century it began to appear with more frequency on names for animals (puppy, dog, butterfly, centaur) and a wide variety of common nouns (school, twaddle, leaf, magazine, jelly, cotton, fossil). But why, exactly, its range of bases expanded at this point is still a mystery.

By the way, when he wrote in the early 1940s Wentworth was convinced that the productivity of -dom did not drop from the turn of the twentieth century on, as figure 4.3 suggests: in addition to scrutinizing the OED, as I have done here, he checked through other dictionaries and collected his own examples, and his study turned up quite a few words. Still, the OED has not added a huge number of examples since Wentworth wrote his article, and it appears that although -dom is still quite productive, it does not now enjoy the enormous popularity it did during the 1880s.

This is just one suffix in just one language, but we would expect that other word formation processes could be tracked in a similar way, showing the different processes most active in a language at any given time.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة