Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Relative clauses

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

223-6

19-1-2023

2867

Relative clauses

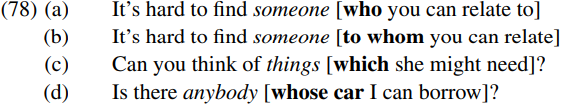

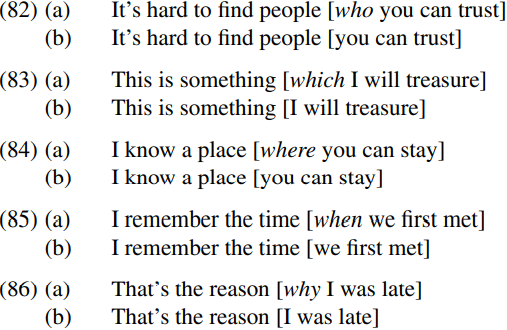

A further type of wh-clause (briefly touched on earlier in relation to (12c), (13), (19) and (20) above) are relative clauses like those bracketed below:

They are called relative clauses because they contain a relative pronoun (who/whose/which) that ‘relates’ (i.e. refers back) to an (italicized) antecedent in a higher clause (generally one which immediately precedes the bold-printed relative wh-expression). Each of the bracketed relative clauses in (78) contains a bold-printed wh-expression which has undergone wh-movement and thereby been positioned at the front of the bracketed relative clause. In (78b) the preposition to has been pied-piped along with the (relative) wh-pronoun whom, so that to whom is preposed rather than whom on its own; likewise, in (78d) the noun car is pied-piped along with the genitive wh-pronoun whose.

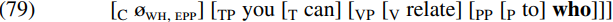

Relative wh-clauses resemble exclamative wh-clauses in that they too show wh-movement without auxiliary inversion. We can therefore analyze them in a similar way, namely as CPs containing a C with [WH, EPP] features but no [TNS] feature. On this view, the bracketed relative clause in (78a) would have the simplified structure shown below at the point where C is merged with its TP complement:

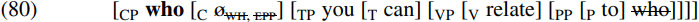

The [WH, EPP] features of the null C attract the closest maximal projection with a wh-word – i.e. the bold-printed relative pronoun who (which is the maximal projection of the wh-word who). Who then moves to spec-CP, thereby deleting the [WH, EPP] features of C and so forming the CP (80) below:

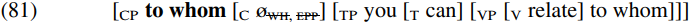

An alternative possibility found in more formal styles is for the whole PP to be preposed, so that to is pied-piped along with the relative pronoun, deriving the structure shown in simplified form below:

The relative pronoun in structures like (81) is spelled out as the accusative form whom in formal styles.

Although the relative pronoun is overtly spelled out as who/whom in structures like (80) and (81) above, relative pronouns in English can also be given a null spellout, so resulting in bare relative clauses (i.e. relative clauses which contain no overt relative pronoun) like those bracketed in the (b) examples below:

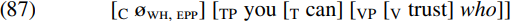

Although the bare relative clauses in the (b) examples don’t contain an overt relative pronoun, there is reason to believe that they contain a null relative pronoun – and hence (e.g.) that (82b) contains a null counterpart of who. For example, the verb trust in (82b) is a two-place transitive predicate which requires a noun or pronoun expression as its complement: since trust has no overt object, it must have a null object of some kind. On the assumption that all relative clauses contain a relative pronoun, the object must be a relative pronoun (or relative operator, to use alternative technical terminology). For concreteness, let’s suppose that the object of the verb trust in (82b) is the relative pronoun who. If so, the bracketed relative clauses in (82a,b) will both have the structure shown below at the point where the null complementizer C is merged with its TP complement:

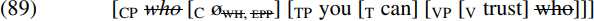

The [WH, EPP] features of the complementizer will attract the relative pronoun who to move to spec-CP and are thereafter deleted (along with the trace copy of the moved pronoun who), so deriving the CP (88) below:

If we further suppose that the PF component permits a relative pronoun which occupies spec-CP position in a relative clause to be given a null spellout, then who in (88) can be given a null spellout in the PF component, so deriving:

One reason why the relative pronoun can be given a null spellout may be that its person/number/gender features can be identified by its antecedent: e.g. who refers back to people in (82a) and so is identifiable as a third-person-plural animate pronoun even if deleted.

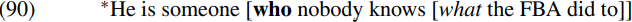

While the analysis of bare relative clauses sketched above is plausible, an important question to ask is whether there is any empirical evidence in support of the key assumption that bare relative clauses contain a relative pronoun which undergoes wh-movement in the same way as overt relative pronouns do. An interesting piece of evidence in support of a wh-movement analysis comes from islandhood effects. As we noted earlier, Ross (1967) argued that certain types of syntactic structures are islands – i.e. they are structures out of which no subpart can be moved via any kind of movement operation (the general idea behind his metaphor being that any constituent which is on an island is marooned there and can’t be removed from the island by any movement operation of any kind). One type of island identified by Ross are wh-clauses (i.e. clauses beginning with a wh-expression). In this connection, note the ungrammaticality of sentences like:

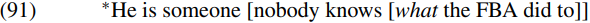

(intended to have a meaning which can be paraphrased somewhat clumsily as ‘He is someone such that nobody knows what the FBA did to him’). In (90), the relative pronoun who is the object of the preposition to, and is moved out of the bracketed did-clause to the front of the knows-clause. However, the did-clause is a wh-clause (by virtue of being introduced by what) and wh-clauses are islands: this means that moving who out of the did-clause will lead to violation of Ross’s wh-island constraint (forbidding any constituent from being moved out of a wh-clause: see Sabel 2002 for a more detailed account of the constraint).

What is of more immediate relevance to our claim that bare relative clauses contain a relative pronoun which undergoes wh-movement is that bare relative clauses exhibit the same islandhood effect, as we see from the ungrammaticality of:

How can we account for this? Given our assumption that bare relative clauses contain a relative pronoun which moves to spec-CP and is subsequently given a null spellout in the PF component, (91) will have the structure (92) below (simplified in numerous respects, including by not showing trace copies of moved constituents):

The relative pronoun who is initially merged as the complement of the preposition to and is then moved out of the did-clause to the front of the knows-clause, and receives a null spellout in the PF component. But since the did-clause is a wh-clause (by virtue of containing the preposed wh-word what) and since wh-clauses are islands, movement of the relative pronoun out of the did-clause will lead to violation of the wh-island constraint. Thus, our assumption that bare relative clauses contain a relative pronoun which undergoes wh-movement provides a principled account of the ungrammaticality of structures like (92).

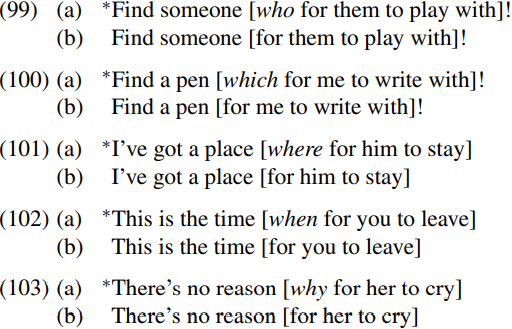

In finite relative clauses like those bracketed in (82)–(86) above, the (italicized) relative pronoun can optionally be given a null spellout. But in infinitival relative clauses like those bracketed below, it is obligatory for the relative pronoun to have a null spellout:

The bracketed structures in (93)–(97) above are control clauses, hence CPs containing a null intransitive complementizer and a null PRO subject. Given the assumptions made here, (93b) will have the partial, simplified structure shown in (98) below:

The relative pronoun will move from VP-complement position to CP-specifier position, and obligatorily be given a null spellout.

It is also obligatory for a relative pronoun to be given a null spellout in infinitival relative clauses containing the transitive complementizer for – as we see from the examples below:

Accordingly, an infinitival relative clause like that bracketed in (99b) will contain a relative pronoun like who which is initially merged as the complement of the preposition with and then moves to become the specifier of the complementizer for, ultimately being given a null spellout.

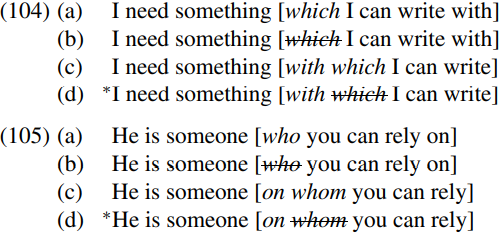

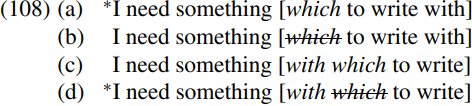

So far, we have seen that relative pronouns are optionally given a null spell-out in finite relative clauses, and obligatorily given a null spellout in non-finite (infinitival) relative clauses. However, there is an important complication which we have overlooked so far, which relates to pied-piping. In (both finite and non-finite) relative clauses in which other material is pied-piped along with the relative pronoun when it moves to the front of the relative clause, the relative pronoun cannot be null but rather must be overtly spelled out – as we see from the contrast below (where strikethrough is used to denote a ‘silent’ relative pronoun with a null spellout, and traces of moved wh-pronouns are omitted):

Why should it be that relative pronouns can have a null spellout in structures like (104b) and (105b), but not in structures like (104d) and (105d)?

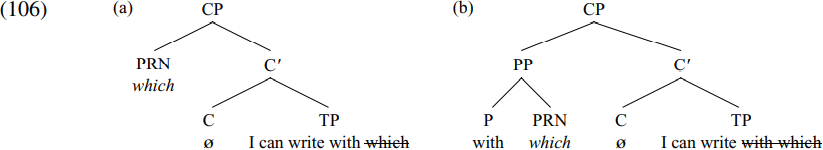

The reason seems to be related to a difference in the superficial position occupied by the relative pronoun in the two types of clause. This positional difference becomes apparent if we compare the superficial structure of the bracketed relative clauses in (104a,b) with that of the relative clauses in (104c,d), shown in (106) below:

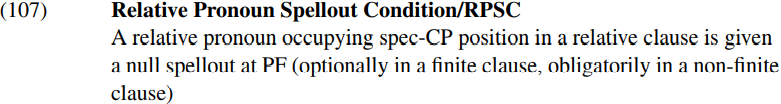

In (106a), the italicized relative pronoun which ends up (at the end of the syntactic derivation) as the specifier of the null complementizer heading the relative clause, and can be given a null spellout. By contrast, in (106b) the relative pronoun remains the complement of the preposition with throughout the derivation, and it is the whole PP with which that is in spec-CP. The descriptive generalization which this suggests is the following:

In accordance with RPSC, which can receive a null spellout in (106a) by virtue of occupying CP-specifier position, but not in (106b) by virtue of occupying PP-complement position.

Since it is obligatory for a relative pronoun in spec-CP to receive a null spellout in a non-finite relative clause, relative pronouns in non-finite relative clauses are spelled out differently from their finite counterparts – as we can see by comparing the examples in (104) above with those in (108) below:

The key difference is that whereas a relative pronoun which occupies the specifier position in a finite relative clause can either have an overt spellout as in (104a) or a null spellout as in (104b), a relative pronoun which occupies spec-CP in an infinitival relative clause obligatorily receives a null spellout as in (108b), and cannot be overtly spelled out – as we see from the ungrammaticality of (108a).

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)