Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Grammaticalization.

المؤلف:

P. John McWhorter

المصدر:

The Story of Human Language

الجزء والصفحة:

17-3

2024-01-08

3207

Grammaticalization

A. Words can be divided into two classes.

1. Concrete words refer to objects, actions, concepts, or traits that any of these have. In other words, nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs: man, happiness, run, overrate, red, distraught, quickly, soon.

2. Grammatical words are those that relate concrete terms to one another or situate a statement in time, space, and attitude. In other words, prepositions, articles, conjunctions, interjections, auxiliaries: in, under, the, but, except, hey!, so…, would, not.

B. A fundamental process in what happens to a language over time is that grammatical words develop gradually from words that begin as concrete.

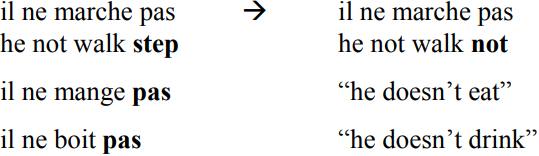

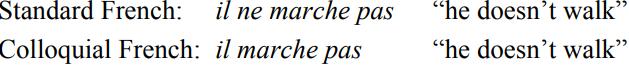

C. The negative marker pas in French.

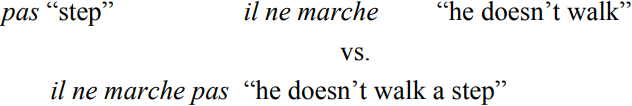

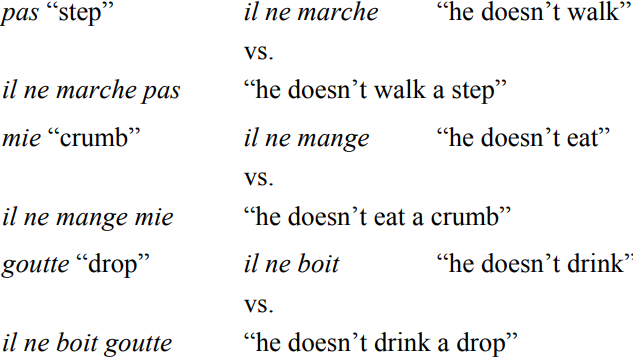

1. In early French, the regular way to negate a sentence was to put ne before it. One did not need to add pas afterwards as in Modern French. At this stage in French, pas still had a concrete meaning, step, and to add pas meant just a stronger version of the negative.

2. At the time, this was part of a general pattern. To make a stronger negation, one added various words to a sentence with ne, depending on what kind of action was involved.

3. In general in language, an expression that begins as a colorful one either disappears (peachy keen!) or dilutes into normality and needs replacing by a new “colorful” expression. In the 1960s and 1970s, for example, to call something or someone lame was pretty trenchant; today, it has diluted into meaning roughly “not especially good” and has been replaced by other expressions among the young, such as from hell.

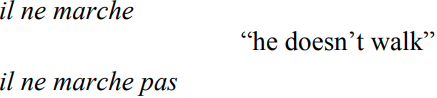

4. In French, the “crumb” and “drop” expressions fell away after a while, but the “pas” one held on—although it began fading in power. After a while, there was no real difference between an expression with pas and one without one:

5. In this situation, pas no longer seemed to mean step at all. By the 1500s, pas started to seem as if it were a new way of saying not, along with ne. And, eventually, it was. This meant that you could use it with any verb, even ones that had nothing to do with walking.

6. Therefore, a word that began as a concrete word for step became a piece of grammar, a word to make a sentence negative. This process is called grammaticalization.

7. The process has gone even further in colloquial French, where speakers tend to drop the ne, leaving pas as the only negator word. The change in pas from “thing” to “grammar” is now complete!

8. Recall that this is a worldwide process, not just something that happens in Europe, or to written languages, or to languages spoken by certain people. In the Mandinka language of West Africa, their grammatical word for showing the future, like English’s will, is sina. This word began as two concrete words, si and na, which mean sun and come. Together, these words form the word for tomorrow: sina or “sun come.” This word for tomorrow was used in expressions with the future so much that it came to be felt as the word for the future itself.

D. Grammaticalization and endings.

1. To return to the issue of how language rebuilds itself: grammaticalization creates not only new words, such as pas, but new endings to replace the ones that sound erosion wears away.

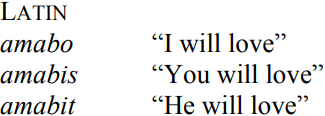

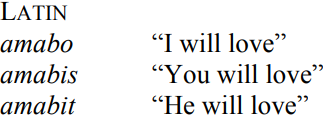

2. For example, in Latin, there were endings expressing the future.

D. Grammaticalization and endings.

1. To return to the issue of how language rebuilds itself: grammaticalization creates not only new words, such as pas, but new endings to replace the ones that sound erosion wears away.

2. For example, in Latin, there were endings expressing the future.

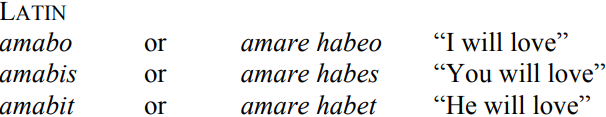

3. But there was a newer way of expressing the future, using the verb habēre “to have.”

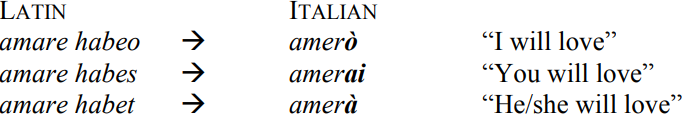

4. Over time, the future endings wore away. But at the same time, the habēre forms began wearing down and becoming endings on the verb that came before them. What began as concrete words— forms of “to have”—became bits of grammar, endings. The result was a new set of future endings, such as in Italian.

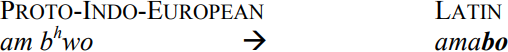

5. Overall, any prefixes or suffixes that you find in a language most likely began as separate words. Languages very often continually create their prefixes and suffixes in this way. For example, this kind of process had created the original future endings in Latin. Latin’s ancestor Proto-Indo-European had had an expression with a verb and a following verb “to be.” This was what created such Latin words as amabo.

E. Grammaticalization and new sounds.

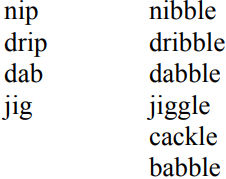

1. Grammaticalization can go so far that it leaves behind bits of material that we barely even think of as suffixes or affixes at all. Consider, for example, this list of related words:

2. We do not usually even realize these words are related, but the -le syllable was once an ending in an earlier stage of Germanic, the family that English belongs to. The ending meant “to do something repeatedly within a short time.”

3. Today, we can’t make new words with that ending, and often, the original word without -le no longer even exists. The ending is just a fossil, but it began as a separate word, now lost to time.

F. Grammaticalization and new tones.

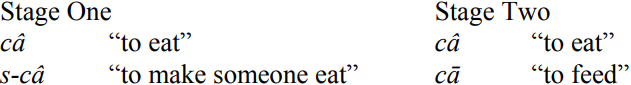

1. Sometimes, grammaticalization can also just leave behind a tone! In many languages in Southeast Asia, there was once a prefix that meant that one caused some action to happen. Here is an example from Lahu, a language spoken in China and various Southeast Asia countries:

2. The s- made speakers pronounce the vowel on a lower pitch. But then, erosion wore away the s- and left just the lower pitch behind. Now, the low pitch alone shows that one means that an action was caused—as if just a tone meant “to make.”

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)