Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Building an alternative: An analogy to definite descriptions

المؤلف:

MARCIN MORZYCKI

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P114-C5

2025-04-16

826

Building an alternative: An analogy to definite descriptions

An essential problem here is this: It seems to be a fundamental property of expressive meaning (or conventional implicatures) that a constituent with such an interpretation can’t contain a variable inside it that is bound from outside it. (Karttunen and Peters 1975 termed this the “binding problem.”) The way around this is to suppose that nonrestrictive modification always involves reference, or at least some form of quantificational independence. The problem faced here is that in, for example, unsuitable word or damn Republican, the modified expression is property-denoting. So how then to reconcile this with the need to keep expressive and at-issue meaning apart from each other in the right way? What do expressive modifiers modify?

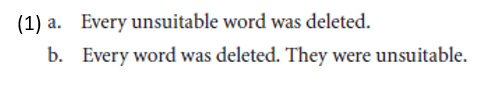

To address this question, it may help to momentarily revisit an old analytical intuition: that expressive meaning (or in any case nonrestrictive modification) involves, in some sense, interleaving two utterances, one commenting on or elaborating the other. Seen in this light, perhaps the Larson and Marušiˇc (2004) paraphrase of (1a) in (1b) is not only apt, but also revealing:

What’s special about (1a) (on the relevant reading) is that it is a way of saying both sentences of (1b) at once. And the linguistic trick that makes (35b) possible is using they to refer back to a plural individual consisting of the set quantified over by every.

Thus an answer to the question just raised presents itself: Maybe what these nonrestrictive modifiers modify is a potentially plural discourse referent such as the one the pronoun in (1b) refers to.

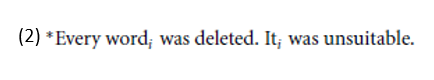

Importantly, the anaphora (1b) would not be possible with a singular pronoun:

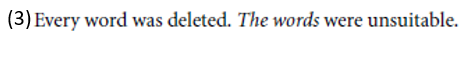

That is, 2) can’t mean “Every word was deleted and unsuitable.” A natural assumption about why this anaphora is nonetheless possible in (1b) is that this they is an E-type pronoun, and consequently is interpreted like a definite description (Heim 1990):

This approach helps avoid an interpretation that includes an element such as “words were unsuitable,” because, unlike kinds, definite descriptions involve a contextual domain restriction.

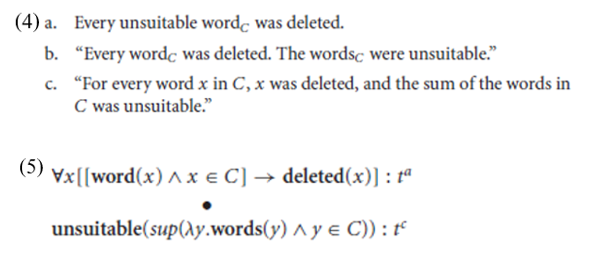

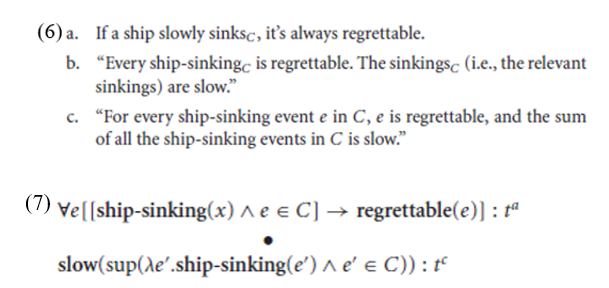

What’s being quantified over in the unsuitable-words example is not, of course, all words, but only the contextually relevant ones – a fact I’ll reflect here using a contextually supplied resource domain variable C (Westerstahl 1985; von Fintel 1994), as in (4) and (5).1

Roughly analogous assumptions are possible for adverbs:

Striving to assemble these interpretations may be a step toward a more adequate general understanding.

It also provides an alternative way of understanding the damn facts in the previous sections. On this view, the damn machine will convey disapproval of only the machine relevant in the context, and the fucking people next door, disapproval of contextually relevant people next door.

1 In addition to contextual domain restrictions, these rough interpretations introduce a supremum operator that loosely corresponds to the definite determiner in the paraphrases. This is not as significant a move, however. Indeed, the Chierchia (1984) nominalizing type-shift ∩ itself has this general kind of semantics (at least extensionally). Note also that I am placing the resource variable C directly in the syntax, as a subscript on the head.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)