Bilinguals

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

246-12

الجزء والصفحة:

246-12

2024-01-02

2024-01-02

1618

1618

Bilinguals

A true bilingual is someone who has been raised from a young age to use two mother tongues and is equally proficient in both: the term does not normally extend to individuals who have an aptitude to learning languages at school or university, or who have lived for a long time in a country where a language other than their mother tongue is used. Such people may in some cases be able to approximate closely to native speaker competence in their new language, but cannot claim to have that language as a mother tongue. Famous English-speaking bilinguals are Richard Burton (Welsh/English), Sandra Bullock (German/English), Charlize Theron (Afrikaans/English) and Mila Kunis (Russian/English).

Leaving aside the languages of recent immigration (around 300 are believed to be spoken in London alone), a patchwork of indigenous minority languages within the United Kingdom reflects historical patterns of settlement and displacement. Welsh, Irish and Scots Gaelic are still spoken in northern and western peripheral areas to which Celtic peoples were displaced following Anglo-Saxon invasions between the fifth and seventh centuries. Two other Celtic languages have been lost: Cornish, the language of Cornwall, died probably in the early nineteenth century but has since been revived and now has a number of speakers raised as modern Cornish–English bilinguals, while Manx in the Isle of Man died as a mother tongue with its last native speaker, Ned Maddrell, in 1974. In the Channel Islands, which became subject to the Crown after the Norman Conquest, Romance varieties similar to French are spoken by dwindling numbers of speakers: Jèrriais in Jersey; Guernésiais in Guernesey and Serquois in Sark; only a handful of Auregnais speakers now remain on Alderney. Norn, a descendant of old Norse, was spoken in Shetland and Orkney and Caithness until probably the early nineteenth century, following Scandinavian settlement from the ninth century onwards. The appearance of monolingualism in the British Isles therefore belies considerable linguistic diversity.

An important kind of arrangement in multilingual communities involves a functional separation between varieties known as diglossia. The term was first coined by Charles Ferguson in 1959, and originally defined as follows:

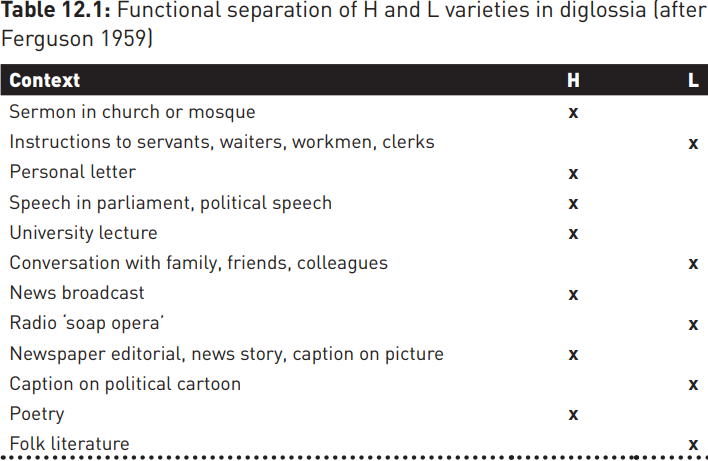

Examples of diglossia include classical and spoken Arabic, High German (Hochdeutsch) and Swiss German (Schwyzertütsch) in Switzerland, or katharevousa (‘Church Greek’) and dhimotiki (‘demotic Greek’, or ‘people’s Greek’) in modern Greece. In all these cases, Ferguson argued, the two related varieties continue to co-exist because each serves a particular set of functions. One, which can be labelled the High (H) variety, is used in a range of more formal settings and functions, while the other Low (L) variety is used in more familiar or intimate contexts. Ferguson illustrates this division of labour as follows:

It is important to note that Ferguson’s schema is indicative, and not all diglossic situations have an identical distribution of H and L functions; nor is the relationship between the two varieties hermetically sealed. Later definitions of diglossia have relaxed Ferguson’s strict criterion that the varieties be related: Fishman (1967), for example, sees a very similar functional separation in many settings where different languages are involved and H and L varieties can be identified. This broader definition encompasses English (H) and Welsh (L) in Wales; French (H) and Alsatian (L) in Alsace, eastern France or Spanish (H) and Basque (L) in the Basque Country, north-western Spain.

Diglossia may or may not involve individual bilingualism. In many diglossic situations, speakers control both varieties and use them according to the circumstances of the speech situation. Early-nineteenth-century Tsarist Russia, on the other hand, was a diglossic society with very little bilingualism: the Frenchspeaking elite generally did not speak Russian (L) and the peasantry generally had little French (H). Brussels, by contrast, is a setting in which widespread French-Dutch bilingualism is not accompanied by a functional separation of varieties and, officially at least, both languages enjoy equal status. There can be little doubt, however, that French now dominates in Brussels, and Fishman has argued that bilingualism without diglossia tends to be a transitional state.

In diglossic communities where most speakers control both H and L varieties, speakers may code-switch between the two. In situational code-switching, a switch may be triggered by a change of topic or situation, or in response to a change of interlocutor, and may exploit the symbolic value or associations of the varieties in question. In a famous 1972 study by Jan-Petter Blom and John Gumperz, party guests in the Norwegian town of Hemnesberget were found unconsciously to switch from the local dialect, Ranamål (L), to standard Norwegian (Bokmål; H) as the conversation turned from domestic or local topics to more public or academic ones. Use of Ranamål seemed to emphasize what the researchers called local ‘team’ values.

In cases of conversational code-switching, however, there is most often no identifiable trigger for individual switches, which can occur with great frequency: it is the switching itself, rather than the symbolic associations of the varieties for the speakers concerned, which becomes an important marker of speech community identity.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة