The phoneme: problems and solutions

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

90-5

الجزء والصفحة:

90-5

2023-12-15

2023-12-15

1273

1273

The phoneme: problems and solutions

We have seen a number of examples of complementary distribution, in which allophones of the same phoneme occur in different environments and therefore lack the potential for functional contrast. In some cases, however, we can identify sounds whose distribution is certainly complementary, but which, for other reasons, we would not wish to consider as members of the same phoneme. The most celebrated example of this kind is that of [h] and  (generally represented by the digraph ng in conventional orthography), which have very different, and certainly complementary, distributions:

(generally represented by the digraph ng in conventional orthography), which have very different, and certainly complementary, distributions:

hear ring

hope singing

Henry singer

ahead long

ahoy! alongside

While [h] only occurs syllable-initially,  is only to be found syllable-finally. These sounds seem to meet the criteria for conditioned allophones, and there are no minimal pairs like hope/*ngope or ring/*rih, so one might want to suggest that they are members of a single phoneme (which we can call ‘heng’ for convenience).

is only to be found syllable-finally. These sounds seem to meet the criteria for conditioned allophones, and there are no minimal pairs like hope/*ngope or ring/*rih, so one might want to suggest that they are members of a single phoneme (which we can call ‘heng’ for convenience).

In fact, there are good reasons for rejecting ‘heng’. Firstly, the two sounds, a glottal fricative and a velar nasal, seem very different in kind: in other words, they fail the test of phonetic similarity. But as our /t/ example showed earlier, allophones can be very dissimilar, so it would be dangerous to give undue weight to this criterion alone. A more important consideration is that there is a natural class of consonants, nasals, to which one member belongs but the other does not, and that this grouping shares a number of properties which [h] does not. Like /n/ and /m/ (but unlike [h]),  has fortis and lenis oral equivalents, and although its distribution is restricted when compared to /n/ and /m/ (both of which can occur syllable initially or syllable-finally in English), it behaves exactly like the other nasals, notably with regard to the homorganicity rule for nasal+ oral stop sequences.

has fortis and lenis oral equivalents, and although its distribution is restricted when compared to /n/ and /m/ (both of which can occur syllable initially or syllable-finally in English), it behaves exactly like the other nasals, notably with regard to the homorganicity rule for nasal+ oral stop sequences.

None of these things are true for the glottal fricative [h], and no meaningful generalizations about  can be framed which could include [h]. It therefore seems intuitively and practically more sensible to view these sounds as separate phonemes /h/ and

can be framed which could include [h]. It therefore seems intuitively and practically more sensible to view these sounds as separate phonemes /h/ and  , with restricted distributions in English. The ‘heng’ question does raise an important problem in linguistics, however: where two competing explanations of the same data are available, how should one choose between them? Generally the principle of Occam’s Razor is applied in such cases, namely that descriptively economical theories should be favored until simplicity can be traded for greater explanatory power. Positing a ‘heng’ phoneme appears descriptively elegant in that it captures a distributional fact about the two sounds involved, but it fails to capture a range of other properties which one putative ‘allophone’ shares with another group of English phonemes.

, with restricted distributions in English. The ‘heng’ question does raise an important problem in linguistics, however: where two competing explanations of the same data are available, how should one choose between them? Generally the principle of Occam’s Razor is applied in such cases, namely that descriptively economical theories should be favored until simplicity can be traded for greater explanatory power. Positing a ‘heng’ phoneme appears descriptively elegant in that it captures a distributional fact about the two sounds involved, but it fails to capture a range of other properties which one putative ‘allophone’ shares with another group of English phonemes.

An assumption we have made thus far, but not stated directly, is that allophones must belong only to a single phoneme: this is known as the biuniqueness condition. It is not difficult to see that if allophones could belong to several phonemes, the ensuing ambiguities would make language much more difficult to process. But the important working principle that allophones belong to one and only one phoneme encounters some notable problems. Consider the following examples from German:

Das Rad  ‘wheel’

‘wheel’

Der Rat  ‘council’

‘council’

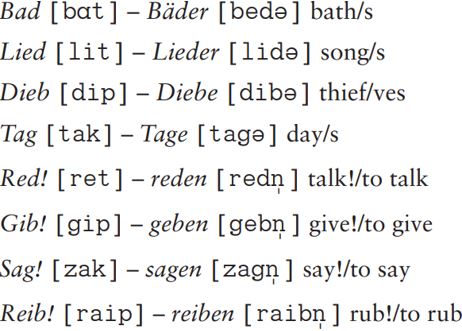

Both words are pronounced with final [t] sound, but the difference in spelling here has a rational basis rather than being simply a historical quirk, as is evident from their plural forms: in the plural of Rad (Räder) the [d] sound is restored, while in that of Rat (Räte) the final [t] remains. This is not merely a fact about Rad and Rat: a whole range of singular/plural pairs have a voiceless word-final consonant which becomes voiced when a suffix is added; the same pattern is observed too for some imperative and infinitive pairs:

The generalization to be drawn here is that voiced consonants are not allowed (or licensed) word-finally in German, but this descriptive statement fails to capture the fact that the [t]s of Rad and Rat are fundamentally different: one reverts to [d] in non-final positions, the other does not. We might want to suggest that the final segment of Rad is ‘underlyingly’ /d/, but to do so we have to sacrifice the biuniqueness condition and claim, in effect, that [t] is an allophone of both /d/ and /t/.

The solution proposed by Nikolai Trubetzkoy of the Prague School was to suggest that, in certain environments, some phonemic oppositions are unavailable or neutralized: this would be the case for the word-final voiced/voiceless contrast in German, which remains available in other positions. A similar analysis can be proposed in the case of nasal+ oral stop sequences in English.

Try saying the following words:

Indeed input

increase invade

The orthographic n here is deceptive. In the case of indeed, it corresponds to [n], but the sound normally produced in input is in fact [m], and in increase it is  (we will come back to invade in a moment). To summarize, the sequences of nasal and oral stops is as follows:

(we will come back to invade in a moment). To summarize, the sequences of nasal and oral stops is as follows:

In all of these cases, the nasal consonant and the following oral stop share the same place of articulation: dental-alveolar, bilabial and velar respectively: the nasal consonant, in other words, is homorganic with the following oral stop. Because the nature of the nasal consonant is entirely predictable from the following consonant, the phonemic contrast between /m/, /n/ and  is neutralized in this environment, which we can indicate via a nasal archiphoneme N in this position (archiphonemes are conventionally represented by capital letters). This phenomenon explains the restricted distribution of

is neutralized in this environment, which we can indicate via a nasal archiphoneme N in this position (archiphonemes are conventionally represented by capital letters). This phenomenon explains the restricted distribution of  which we discussed above.

which we discussed above.  occurs in sequences represented orthographically by ng, representing syllable-final N+g sequences, where our homorganicity rule would predict that N is realized

occurs in sequences represented orthographically by ng, representing syllable-final N+g sequences, where our homorganicity rule would predict that N is realized  before the velar consonant. In most varieties of English, final /g/ in this environment was lost, leaving

before the velar consonant. In most varieties of English, final /g/ in this environment was lost, leaving  in syllable-final position, but not available in other positions (in some varieties this change did not happen: in north-west England, for example, thing is still realized

in syllable-final position, but not available in other positions (in some varieties this change did not happen: in north-west England, for example, thing is still realized  ).

).

But what of the nasal consonant in invade? /v/ is a labio-dental consonant and our rule predicts, correctly, that the nasal will accordingly be the labio-dental  .

.  is not a phoneme of English because it occurs only in this position, where no contrasts with other nasals are possible.

is not a phoneme of English because it occurs only in this position, where no contrasts with other nasals are possible.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة