Lewis Carroll and the art of English phonotactics

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

83-5

الجزء والصفحة:

83-5

2023-12-14

2023-12-14

1434

1434

Lewis Carroll and the art of English phonotactics

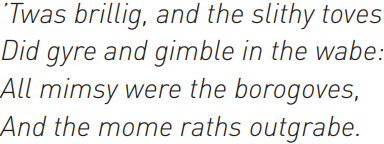

Languages demonstrate remarkable economy in using a small number of resources to produce all the words they need, not just for their existing lexicon (or stock of words), but also for an ever-growing number of new words: quidditch, satnav, website and selfie were all unknown 30 years ago, but have settled comfortably into the English language. This creativity is not haphazard but rule-governed: English speakers would not similarly have accepted new words like bzork, thlick or drailx, even though they use familiar English sounds. The nonsense words of Lewis Carroll’s famous poem Jabberwocky, on the other hand, pose no problem:

No native English speaker – probably not even Carroll himself – can say what brillig, gyre, wabe or borogoves mean (though some online have had a stab at doing so), but the poem works because all these words, and the many other unfamiliar inventions elsewhere in Jabberwocky, could exist in English: they just happen not to. They represent what linguists call accidental gaps in the lexicon. Carroll’s creations all respect the phonotactics of English, i.e. the constraints on the way its speech sounds can be combined.

Phonotactics are highly language-specific. While English allows words to begin sp-, st- or sk-, for example, Spanish does not, and Spanish learners of English often struggle with these forms initially (‘I espeak Espanish’, etc.). English, by contrast, rules out initial sequences such as vzd- or vn-, which present no difficulty to Russian speakers in such words as vzdor (‘nonsense’) or vnuk (‘grandson’).

The distinctive speech units of a language are known as phonemes, and these provide the essential building blocks from which all well-formed words (or lexemes) in that language are produced. Phonemes can therefore be thought of as the atoms of a language, and just as atoms have subatomic particles, so phonemes divide into smaller units known as allophones.

Let’s look again at the leap and cool examples above. For most (but not all) British English speakers, the two sounds are ‘clear’ l  in the former and ‘dark’ l

in the former and ‘dark’ l  in the latter. These sounds do not have the potential to distinguish words: pronouncing cool with ‘clear’ l results in a pronunciation which might correspond to that of Irish or Welsh English speakers (who generally use clear l in all positions) but the same word, cool, will be understood.

in the latter. These sounds do not have the potential to distinguish words: pronouncing cool with ‘clear’ l results in a pronunciation which might correspond to that of Irish or Welsh English speakers (who generally use clear l in all positions) but the same word, cool, will be understood.

Using ‘dark’ l in leap likewise might make your pronunciation sound slightly Russian (Russian does not have clear l), but the meaning would be unchanged. If, by contrast, we were to replace the  of leap with a [h], a [k] or a [p] sound, then different words (heap, keep and peep) would be understood.

of leap with a [h], a [k] or a [p] sound, then different words (heap, keep and peep) would be understood.

Clearly there’s something more important from an English speaker’s point of view about swapping [l] for [h] than [l] for  in this environment. A phonologist would say simply that [l] and

in this environment. A phonologist would say simply that [l] and  are allophones of the phoneme /l/, which English speakers perceive to be in some sense ‘the same’. It is important to realize that languages can organize the same sounds in different ways: in Polish, for example, the distinction between clear and dark l is phonemic, i.e. they do have the potential to distinguish words, as for example in luk ‘skylight’ and łuk ‘bow’.

are allophones of the phoneme /l/, which English speakers perceive to be in some sense ‘the same’. It is important to realize that languages can organize the same sounds in different ways: in Polish, for example, the distinction between clear and dark l is phonemic, i.e. they do have the potential to distinguish words, as for example in luk ‘skylight’ and łuk ‘bow’.

Two points need to be made here. Firstly, you may have noticed a subtle notational change in the previous paragraph. When we referred to ‘the phoneme /l/’, the square brackets we have consistently used for speech sounds were replaced by slants. This is because, when we talk of a phoneme, we refer not to a speech sound but to an abstract unit. The phoneme /l/ might be pronounced or realized  , according to the context, and since the phoneme /l/ doesn’t necessarily mean the sound

, according to the context, and since the phoneme /l/ doesn’t necessarily mean the sound  , we could in principle use any symbol we liked between the slants, for example

, we could in principle use any symbol we liked between the slants, for example  . In practice, however, linguists generally use an IPA symbol which corresponds to one of the more common allophones. This can occasionally cause confusion, as in the case, for example, of the phoneme /æ/ in words such as hat, pack and map. Here / æ / was chosen because it corresponded to the (now rather old-fashioned) RP pronunciation that was de rigueur for BBC newsreaders until around the 1960s. These days, of course, most English speakers say [hat] rather than [hæt], but textbooks retain /æ/ by convention to indicate the vowel which distinguishes hat from hot, hit, hut, height, etc., even though the phoneme is realized in a variety of ways and relatively rarely as [æ].

. In practice, however, linguists generally use an IPA symbol which corresponds to one of the more common allophones. This can occasionally cause confusion, as in the case, for example, of the phoneme /æ/ in words such as hat, pack and map. Here / æ / was chosen because it corresponded to the (now rather old-fashioned) RP pronunciation that was de rigueur for BBC newsreaders until around the 1960s. These days, of course, most English speakers say [hat] rather than [hæt], but textbooks retain /æ/ by convention to indicate the vowel which distinguishes hat from hot, hit, hut, height, etc., even though the phoneme is realized in a variety of ways and relatively rarely as [æ].

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة